Indigenous Stewardship at San Vicente Redwoods: Past, Present, and Future

photo by Ian Bornarth.

There and Back Again

Marcella, one of two women in the Amah Mutsun Land Trust’s Native Stewardship Corps during her tenure, spent four years of her weekends driving between her home in Las Vegas to practically turn around and travel back to the Santa Cruz mountains for the work week. Marcella would arrive every Monday with intention: to “restore the landscape and relearn the purposes and tending of the plants.” “It’s mainly fieldwork that varies day-to-day and week-to-week. I like that,’ she said.

“I’m connecting with family and culture.”

photo by Ian Bornarth

Consequences of Separation

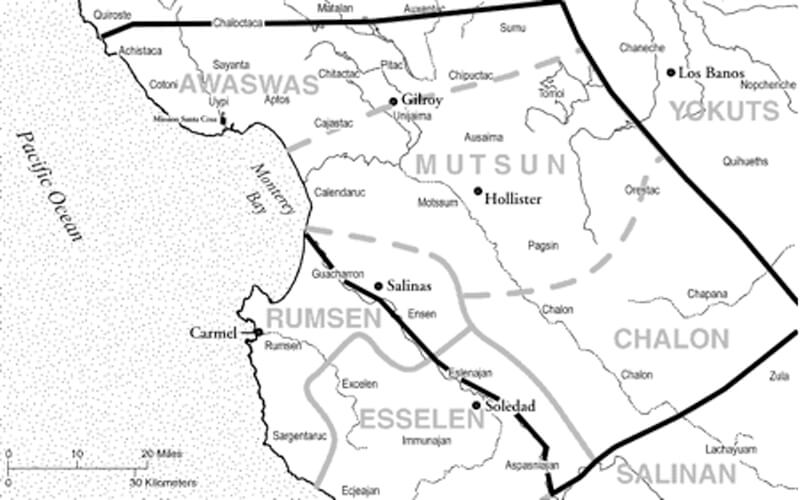

Historic accounts of California by early Europeans paint a picture of its thriving natural bountysee footnote number 1. A large village site of “first contact” with Indigenous Peoples in the region, described during the Portolá Expedition, the first recorded European land entry into California, is thought to be Quiroste Valley in the Santa Cruz mountains regionsee footnote number 2–a region once home to 20 politically distinct peoplessee footnote number 3. But the ensuing Spanish missions systemically began the forced removal of Indigenous Peoples from their lands to be integrated into missions and converted into what they intended to be god-fearing agrarian workers. This tragic separation from the land and culture has been profound. Today, the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band trace their ancestry to those who survived the brutal missions of Santa Cruz and San Juan Bautista. And with their ancestors’ removal went eons of knowledge of and experience with the land, flora, and fauna.

map from Amah Mutsun Land Trust

The flourishing plants and wildlife described in historic accounts of California were not a sign of untapped, limitless resources but rather largely the result of finely tuned stewardship practices of Indigenous Peoplessee footnote number 1. In many ways, we are still uncovering and re-establishing the sciences that reinforce traditional Indigenous knowledge and techniques. Since their removal, they have created the Amah Mutsun Land Trust as a response to tribal elders reminding them of their obligation to Creator. Their removal also played a significant role in the declining numbers of native plants and wildlife, accelerated by the overuse of natural resources, fueled by colonial and industrial strides toward “progress” and “development”. Helping Indigenous peoples regain leadership roles in conservation and revitalize their cultural connection to ancestral landscapes will help us all.

Training By Fire

Nico, a member of the Amah Mutsun Land Trust Native Stewardship Corps who lives on a reservation near Clear Lake, was the youngest Native Steward on the survey field crew. He chaperoned his brothers while they attended Amah Mutsun Land Trust’s Coastal Stewardship Summer Camp for Native Youth but he quickly became involved himself, moving into a high school internship that included fire training and hands-on experience reducing potential fire fuels in Douglas-fir forests. After graduating, Nico spent three years on the Native Stewardship Corps doing lots of work at Quiroste Valley. He always knew he wanted to work outside but, he continues to happily load music playlists on his phone for the drive down to the Santa Cruz mountains because he likes this work.

photo by Orenda Randuch

Fuels and Fire Tools

Unpredictable and unusually extreme weather may be wreaking havoc but conditions on the ground and the increased catastrophic wildfires can be traced back to the loss of Indigenous stewardship of forests. When the 2020 CZU Fire, which burned 86,000 acres in the Santa Cruz mountains, reached San Vicente Redwoods, the flames seemed to cause more damage in areas where trees had grown back too close together–the result of its logging past–or where more fuels like branches and dry brush had built up over the century or more of fire suppression.

photo by Ian Bornarth

Beginning in the late 18th century, Spanish missions barred Indigenous Peoples from utilizing small fires that can reduce fuels, support the growth of fire adapted native plants, and return nutrients to the soil–a tool they had used to care for the land and the food sources they relied on for millennia. Taking fire suppression even further, for nearly 100 years the U.S. government’s policy for all federal land management agencies was to fight all fires even those in remote wilderness areas.

photo by Mike Kahn

However, since becoming conservation land, and before the CZU fire, San Vicente Redwoods had been the site of a traditional fire ceremony performed by the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band and prescribed burns by CalFire. These and other fire management techniques combined Indigenous knowledge and the latest science. Areas of San Vicente Redwoods that had been treated with cultural and prescribed burns showed signs of burning less intensely in the CZU fire, and shaded fuel breaks–a break in vegetation to act as a speed bump for fire–were credited with aiding CalFire while they prevented the fire’s spread to nearby communities.

Despite its varying intensities, all of San Vicente Redwoods was subjected to the CZU fire in 2020. But an opportunity rose from the ashes, although it looked similar: soil. The forest understory is often covered in dense vegetation but with that cleared away by the fire and the soil exposed, culturally sensitive areas, such as Indigenous archaeological sites, can be better identified and studied for evidence of Native plant and animal use.

Family Corps

Lupe, a member of the Native Stewardship Corps since 2016, has worked with the team on countless projects across the Santa Cruz mountains and the greater traditional Amah Mutsun territory over the years. “We’re like a family, we take care of each other out here.” In 2019, Lupe met Alec Apodaca, Ph.D. candidate at the Archaeological Research Facility at U.C. Berkeley, through a project with the Native Stewardship Corps when Alec first became a consulting archaeologist with Amah Mutsun Land Trust. “Alec is a great partner,” Lupe said. Although Alec is neither a member of the tribe or the stewardship corps, he’s witnessed the dedication of the stewardship family while working with them on projects since 2016.

“We’re like a family, we take care of each other out here.”

photo by Orenda Randuch

Science and Stewardship

To expand on previous studies and visits at San Vicente Redwoods, U.C. Berkeley and the Amah Mutsun Land Trust compiled a scope of work for an integrative cultural resource survey to monitor forest health, botany, pathology, entomology, and archaeobiology in both an existing and a new study area over several years. Experienced crews of U.C. Berkeley and Amah Mutsun Land Trust’s Native Stewardship Corps would identify and measure botanical resources, fuel loads, cultural, and ecological resources across the sites over two weeks to establish a baseline. Among the field crew were several Amah Mutsun Tribal Band members working to reconnect with their ancestral lands and knowledge through the Native Stewardship Corps including Lupe from Fresno in the south, Nico from Lake County in the north, and Marcella from Las Vegas in the east. Although they all came from different points on the compass, each traveled many hours from their homes to reconnect with their ancestral home and each other.

photo by Ian Bornarth

Realities of the Work

Alec says the Native Stewardship Corps are friends and family, telling jokes, listening to music, eating good food made by Lupe, and camping together while they work on these projects. But while part of Alec’s role is to help the stewards with the cultural resource surveys, reports and studies, they have helped him to understand the realities of doing this stewardship work. “It's not easy physically or personally. Their ancestors were significantly disrupted beginning with the missions. Most of them don’t get to live in their ancestral land today. They leave their families to come do this work,” he explained.

But even after years of travel and staying in spike camps, the stewards remain committed and interested in the survey work ahead. “We get to see what the ancestors were doing, eating, and what tools they had,” Lupe said. So, they loaded up survey equipment, gear and supplies into special vehicles to get to ancestral sites–miles inland from the coast and difficult to reach even with guides–in the vastness of San Vicente Redwoods.

Cultural Landscape Research

Saucers carved out of rock by years of repeated use known as bedrock mortars mark the place that hundreds if not thousands of Indigenous Peoples sat and milled ingredients, like dried acorns, in circular motions against the bedrock with a stone pestle for food and medicine. Nearby, two large pieces of shiny, sharpened rock called Monterey chert which were often used as tools were found. Much like a modern kitchen, this Indian mortar indicates that not only tools but also a midden, where refuse from the work such as nut, shell, bone, or tool remnants, might be found with the promise of unlocking so much more information. “If we find hundreds of shells, bones, charcoal, seeds, that may indicate a food processing or habitation site,” Alec said.

photo by Ian Bornarth

The field crew dug in. They started by collecting surface soil samples, two liters at a time, tagging the sample location with a high precision GPS unit, and sifting the soil through wood framed screens in search of pieces of limpet and turban snail shells and other things obscured in the dirt. After counting, weighing, and identifying, the crews carefully return the materials right back to the sample location. This “catch-and-release” is a fundamental part of Amah Mutsun Land Trust’s approach to survey. Catch and release allows for archaeological preservation by documenting the object in place and returning it to where it was found gathers the information needed in a low impact way respecting the object’s place in history and in the environment. Even the dirt itself is a clue, Alec said, as soil in a midden area would be darker and greasier as a result of cooking the food and its residual organic content.

In most cultural resource studies today, archaeological assessment usually takes place independently from biological surveys, and perhaps even by different work crews. From the perspective of Amah Mutsun Tribal Band, vegetation and wildlife in which they maintained close relationships with for countless generations also constitute cultural resources, containing similar aspects of significance that, say, an archaeological site may have. In other words, from this view there is no division between cultural and natural resources, and they should be studied comprehensively using Tribal perspectives.

While the crews systematically scour the landscape for the presence of archaeology, they also document ethnobotanical resources and vegetation, even abiotic resources, such as viewsheds, rock outcroppings, and natural spring sources whenever they are encountered. These types of baseline efforts to identify and document cultural resources also allows Amah Mutsun Tribe members space to re-access and re-engage with cultural landscapes for the first time in several generations since colonization and forced removal from their ancestral areas. Centering Indigenous perspectives and participation towards the documentation of cultural landscapes is what makes Amah Mutsun Land Trust’s approach to cultural resource studies a more holistic effort and a nexus for making decisions regarding the revitalization of ancestral lands and cultural practices.

Planting Sites and Signs of Respect

While plant remnants unearthed in the soil could provide valuable information about Indigenous foodways and subsistence, certain information could be gleaned from plants still growing in the earth as well. As part of the vegetative mapping survey, visual assessments looked to identify dominant trees in different areas as well as look for culturally significant plants, important to Indigenous Peoples, growing near one another that may indicate relict patches from Indigenous tending in the past. Relict patches sometimes look unusual in their growth, composition, and location and Alec says can be associated with other significant cultural resources like archaeological sites or springs. Although San Vicente Redwoods burned in 2020, many native plants are adapted to California’s natural wildfire cycle–which is one reason fire was such a useful Indigenous stewardship technique–so, some native plants are not only adapted to regrow following a fire but can also help to indicate the potential presence of a cultural site.

photo by Ian Bornarth

Among the profuse regrowth of native, fire-adapted plants capitalizing on the glittering, bare soil and extra space and sunshine at San Vicente Redwoods left behind by the 2020 CZU fire were bright field poppies, purple lupine, and several foot tall Yerba Santa–an important medicinal plant used to treat an impressive array of symptoms. Amidst the freshly sprung jungle jockeying for sunlight, the field crew found plants used for fishing including wild cucumber which was used as a fish poison and wild irises which were used to make “100 year” fishing nets. The nets required so many irises they were managed in beds and the nets would be passed down to following generations.

Several plants providing important food sources like California blackberry, Indian lettuce (sometimes referred to as miner’s leaf lettuce), and Indian potatoes were found as well. Indian potatoes are the corms of wildflowers commonly called blue dicks but as Marcella pointed out using the Mutsun names for the native plants and animals they cared for long before today’s common names for them were given is a small act of respect. “It's breathing some life back into it and strengthening the relationship with the plant. Language revitalization is a big part of Amah Mutsun Land Trust’s mission,” Alec related. Their relationship with culturally important plants, played a role in finding another culturally important site.

photos by Ian Bornarth

Eco-Archaeology

A small, flat grassland meadow lined by oak trees, whose acorns were an Indigenous food staple, hinted at another potential cultural site. Scans from Ground Penetrating Radar confirmed and helped map strategic excavation grids for potential artifact rich features, like earth ovens. The field crew, flags in hand, walked side by side an arm’s length apart flagging promising looking finds on the surface. Thanks to the help of tunneling gophers, referred to as bioturbation, pieces of shell, chert, and groundstones–cylindrical rocks like a rolling pin–that would have otherwise likely been a ways underground were visible right on the surface. Lupe, an experienced excavator, was not surprised. “You never know what you’ll find near a gopher hole,” he laughed.

The excavation plots were selected by areas with the most flagged items. Lupe and Nico, a first-time excavator, gently peeled back the grass and outlined their 1/2 meter by 1 meter plots, and removed 10 cm soil samples a layer at a time. Some artifacts and biofacts were large enough to be discovered in the layers of the excavation plot including the exciting finds of two large rock scallop shells, a faunal rib fragment with marks in straight lines indicating the work of butchering with a tool rather than the puncture wounds of a predator’s teeth, and projectile point fragments made of local Monterey chert – including a point made of an exotic obsidian source. “We can test the geochemical fingerprint of obsidian artifacts and pinpoint their location to faraway places in California, or further” Alec noted.

The buckets of the remaining soil samples are then sifted on the ⅛ inch screens where Marcella and other crew members expertly pick out tiny–approximately 0.3 mm in size– bits of shell, bone, and chert. Interestingly, miles away from where they would naturally be found, they collected many pieces of shellfish, abalone, sea urchin, crabs, anchovies, seaweed limpets and obsidian.

photo by Orenda Randuch

photo by Orenda Randuch

Remarkable Remnants

One of Marcella’s favorite finds from the screen was a piece of worked chert with visible waves in its fracture lines–evidence of the force of hitting another rock while it was being shaped and sharpened. Chert was the locally sourced glassy, marine sedimentary rock from the area we know as Año Nuevo State Park today. The area’s premiere cutting tool, chert was used for tools that needed to be sharp such as knives and projectile points, like the one discovered here, for hunting tools. Just as the style of clothes can help to identify the place and period they are from, once the form of the artifact can be confirmed, Alec says the projectile point can help provide a relative chronological date of the site, like bell bottom pants in the 70s.

Unlike the tool and projectile point made of chert from Año Nuevo, obsidian doesn’t form in the volcano-less Santa Cruz mountains. So, the small pieces of rock the field crew found that may have been obsidian were particularly exciting to Nico. “It would mean it had been traded,” Nico said. And if it is indeed obsidian, Alec says x-ray fluorescence can reveal its geochemical fingerprint and match it to a known source in California. “It could help piece together broader trade routes and how this site fits into regional trade across the broader San Francisco Bay Area,” he explained.

Another unexpected find from afar was the sheer amount and diversity of shells. Nico was surprised by the number of shells found at the site because of the work it would have taken to carry them so far from the ocean. Small limpets may have hitched a ride on seaweed harvested to wrap food–keeping it cool and moist like a modern-day cooler–but the large, dense rock scallop shells found at the site? Surely, their weight wouldn’t have been born all these miles up rugged terrain without notice. Alec said they haven’t been found at other sites in the area. Furthermore, purple hinge rock scallops could live in the lower tidal zone, meaning someone may have to dive to get them, he elaborated.

Finding fewer animal bones and nuts than they did shellfish remnants so far inland was certainly unforeseen. However, plant matter which would have been much lighter to transport but wouldn’t be as easy to find in the soil today, due to their more fragile composition, may be discovered from the soil samples and provide much more information about culturally important plants.

photo by Orenda Randuch

photos by Orenda Randuch

Learning in the Lab

Was this a seasonal site? Alec says his early speculation is that this site may have been a seasonal village used during cooler seasons as a satellite of a larger village, like Quiroste, where tribes would gather. The amount of shells found certainly supports a large amount of food being sourced along the coast and processed here. Although much more evidence may come out in the wash–literally–through floating the soil samples to find evidence of fish and examining soil for remnants of acorns and hazelnuts can further piece together the food sources and time of year people were processing food here.

Float Samples

An emerging archaeobiology technique in California is soil flotation and the analysis of microecofacts–very small biological artifacts unaltered by humans–like fish scales and seeds that might not be found through other means can float right to the top. Then, the buoyant sample of microecofacts will be examined through a microscope for insights into the traditional food sources of the Amah Mutsun’s ancestors and, through isotopic studies on shellfish samples, which can determine when the shellfish were harvested from the ocean possibly even help to narrow down whether the site was used year-round or seasonally.

Phytolith Analysis

A tiny key into the past, grasses can unlock details of the use of fire in Indigenous stewardship in these grassland prairies. Grasses produce abundant amounts of identifiable phytoliths, minute silica particles formed in plants that can persist in soils for centuries. Measuring the densities of these grassland phytoliths from samples taken across the landscape can help paint a picture of ancient biotic patterns of vegetation around the site.

With so much to cover in the field, lab work will be key in finding even more than meets the eye. U.C. Berkeley’s access to labs, equipment, and students enables this very intensive, and hopefully enlightening, work.

photo by Orenda Randuch

What’s Next

Lab work including soil flotation, sorting specimens and other analysis is underway at U. C. Berkeley, but the thorough and comprehensive projects will likely continue through 2023. While we await revelations the surveys may provide about Indigenous stewardship of the past, what lessons do the field crew hope can be brought to San Vicente Redwoods’ stewardship in the future?

Marcella hopes fuel reduction projects will continue to prevent soil damage–because if a catastrophic fire becomes intense enough, the soil’s nutrients and microbes that feed the forest can be destroyed. Prescribed burns are a helpful tool for fuel reduction projects to reduce dry brush, branches and vegetation on the ground that can feed a fire allowing it to burn more intensely, spread faster, and even climb higher into tree canopies. And as Nico added, cultural burns–smaller fires, ceremonial in prayer, can be used to steward native plants important both culturally for food, medicine, and raw materials, as well as for wildlife.

photo by Ian Bornarth

Cultural burning was so intrinsic to Indigenous culture that agriculture may not have been needed because the relationship with cultural burning was so productive, but this is a concept that is still debated, Alec said. He noted the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band would like to reestablish cultural burning to revitalize the landscape. “But how and where do you start?”, Alec asked. “It’s hard to retrace the locations of the landscape where burns took place, the burns were possibly so light on the land that they may not have even left scars on certain trees for us to look at centuries later,” he continued. “Looking at the multiple records of evidence of how it was done can help make these really big decisions.”

Alec hopes the research can guide stewardship, that we can take lessons from the past to help us try to undo some of the changes in the land over the last 200 years. But he also pointed out the research itself can provide a pathway forward for Indigenous stewardship. “It not only provides opportunity for Indigenous participation, so they can have a say in how to treat discoveries, and reconnect with their culture and ancestral land, but it also provides valuable experience to become leaders in the field science where their Tribal perspectives have been sorely missed.”

“It not only provides opportunity for Indigenous participation, so they can have a say in how to treat discoveries, and reconnect with their culture and ancestral land, but it also provides valuable experience to become leaders in the field science where their Tribal perspectives have been sorely missed.”

More to Explore

- Watch Amah Mutsun Land Trust and UCLA researchers use eDNA to track endangered Coho salmon at San Vicente Redwoods

- Watch Alec Apodaca and Alexii Sigona Under the Redwoods for The Historical Ecology of Indigenous Stewardship Practices in Northern Santa Cruz

- Hear from Amah Mutsun Land Trust and Tribal Band Chairman Valentin Lopez in The True Riches of Relationships with the Land

Resources

Interested in digging a little deeper? Here are some resources with more information indicated in the story above:

Anderson, M. Kat. "Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge and the Management of California’s Natural Resources." University of California Press, 2005. https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520280434/tending-the-wild

Coastside State Parks Association. “Quiroste Valley Cultural Preserve.” Originally published June 1, 2016, https://www.coastsidestateparks.org/articles/quiroste-valley.

Amah Mutsun Tribal Band. “History.” Accessed September 19, 2023, https://amahmutsun.org/history.

Milliken, Randall. "A Time of Little Choice: The Disintegration of Tribal Culture in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1769-1810." Malki-Ballena Press, 1995