What is Stewardship?

Thriving Botanical Bounty

Because Cotoni-Coast Ridge harbors a wide diversity of habitats, the first step in stewarding the property is to better understand it. Before purchasing any property, we perform multiple site visits to assess conditions and identify natural resource values. For this property, however, we wanted to deepen our knowledge of what grows on the property, which areas have the highest stewardship needs, and what are the best ways to address those needs. To gather this information, we hired a botanist to research the area. He is now spending time on the property in order to study it up close.

So far, the research indicates that this land is even more exceptional than the initial evaluation indicated. The amount of intact native vegetation is highly unusual, making it exceedingly important for conservation. At least 168 different plant species grow there in eight distinct vegetation communities, including thriving purple needle grass grasslands. California grassland is one of the most endangered ecosystems in the United States and the lovely purple needlegrass is becoming increasingly rare in the Santa Cruz Mountains.

Even with more learning to come, this botanical study already is shaping our stewardship plans for Cotoni-Coast Ridge and efforts to protect purple needle grass and many other plants in this captivating landscape.

Wildlife Monitoring

Stewarding redwood forests involves exploring which animals use the land and how they use it. Wildlife cameras play a key role in gaining that knowledge. We install motion-triggered cameras on all of our properties, leaving the equipment in place for months to track wildlife activity over extended periods. The resulting images tell us a great deal about the conservation habitat values we are responsible for keeping healthy and thriving.

The cameras have captured images of foxes, raccoons, opossums, skunks, badgers, bobcats, mountain lions, hawks, golden eagles, wild turkeys, even a peacock, and other animals doing all sorts of wild things like chewing, scratching, marking territory, howling, playing, and running.

When we installed cameras at the site of one of our creek restoration projects we recorded more than we expected. The project involved the strategic placement of logs to help create an instream habitat for salmon and other aquatic species, but the cameras photographed bobcats, mountain lions, and other creatures using the logs as bridges to cross the creek. Restoration projects like these often provide more benefit for wildlife than we intend.

While the images are fun to look at, they also inform us and our partners how we steward the land. We might avoid areas where bobcats are leaving their scent so as not to interfere with potential mating cues. We might route public access away from corridors heavily used by wildlife. If we capture images of human trespassers on our properties, we may need to reinforce our gates or otherwise ensure that trespass is not threatening the land in any way. Monitoring by camera is critical to knowing just what’s out there in the wild.

Rocks and Roads

Both removing roads from the forest and maintaining roads in good working order compose a big part of our land stewardship activities.

Over the years we and our partners have been busy with loud, dirty, vital roadwork in the San Vicente Redwoods. This 8,500-acre property is bisected by Warrenella Road, a long dirt thoroughfare that is essential for property management today and will be a key road for public access in the future. In early 2017, the heavy winter rains severely damaged sections of Warrenella Road, leaving areas unpassable from boulders, sinkholes, and deep cracks in the ground. To prevent further erosion, we have been “rocking” the road.

With our partners at San Vicente Redwoods and skilled contractors, we repurposed “overburden” rock (discarded, unwanted rock) from a defunct quarry on the property. Using excavators, bulldozers, rock screeners, and more, we processed the rock and moved it onto six miles of dirt road to create a solid, yet permeable, surface that can withstand harsh weather and frequent use. This project is a great example of creative reuse–reusing abandoned industrial material to solve road problems.

Re-creating Resilient Forests

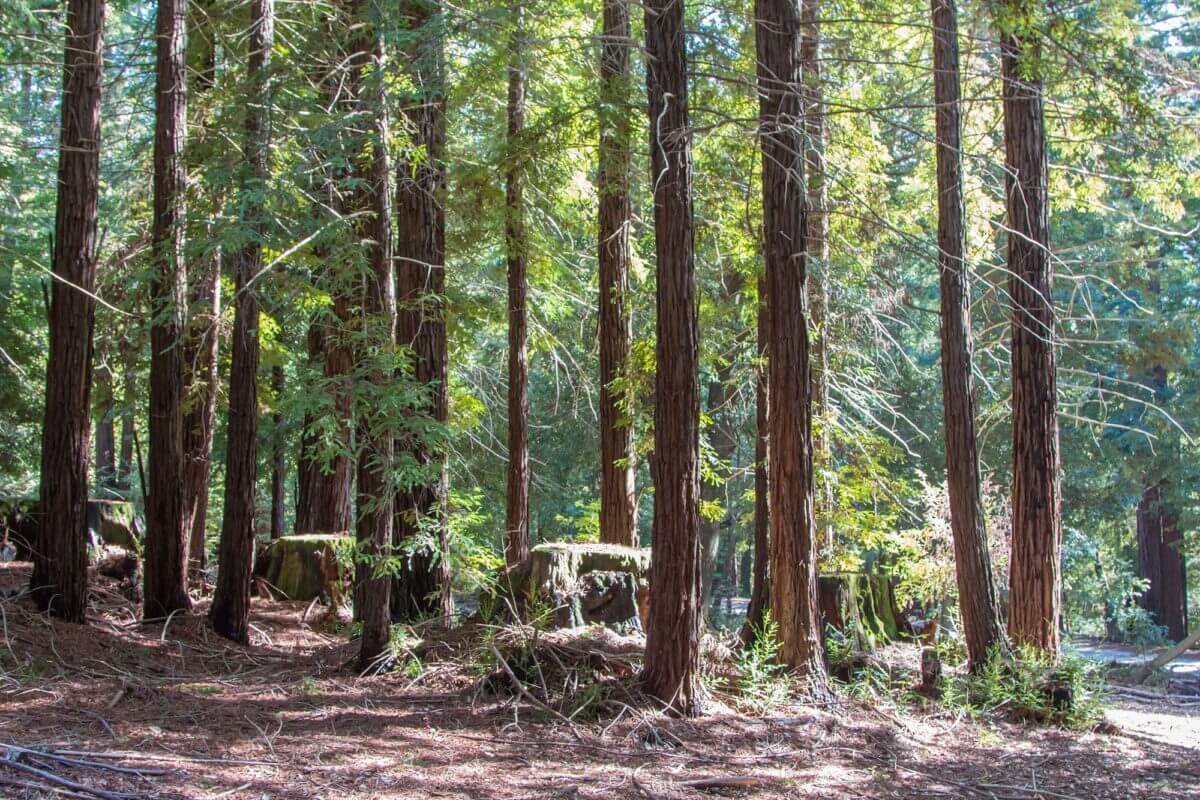

Some of the woodlands in the Santa Cruz Mountains are far denser than those in more pristine natural forests. Clear-cut logging in the 20th century left stumps, and from each of these numerous small redwoods now grow. Over the same period, people suppressed wildfires, leading to a greater density of trees than Mother Nature intended. Some fire in the forest is good–it clears brush and thins out the weaker trees, thereby allowing the stronger, remaining trees to thrive. Overgrown forests include small, thin trees with deadened lower branches. With intense competition for sunlight, water, and nutrients in these thickets of trees, growth on the forest floor diminishes, and forests become less diverse. These forests are also drier, and therefore more likely to be completely destroyed by fire, as well as more susceptible to disease, pests, and drought.

This type of stewardship work is slow going, and, really, it never feels great to cut down a redwood tree. But the remaining trees (and the forest overall) are tougher because of it. Their branches get bigger, stretch out, and create complex canopies in the treetops. As they grow, they sequester more carbon. New growth sprouts on the forest floor. Inch by inch, we are returning these forests to their natural state: resilience.