Ghost Redwoods – Solving the Albino Redwoods Mystery

by Zane Moore, Plant Biology Ph.D. student, U.C. Davis

Coast redwoods are the pinnacle of tree species in regards to height, volume and biomass. They’re masters at removing carbon out of the atmosphere and adding it to their massive trunks. Like huge solar panels, a large redwood tree has enough needles to cover over an acre, sometimes over two and a half, and is the fastest growing plant on the planet, with large trees adding around 1,500 pounds of wood every year. Their efficiency at capturing sunlight is unmatched.

Dale Holderman, a Big Creek Lumber forester, discovered an albino redwood in Soquel that produced pollen after the 1976 drought. He decided to cross-pollinate green cones and the crosses astonished him. Some were green, others white, but some were variegated half-and-half — the first known chimeric redwoods. Photo by Audrey Moore

Sometimes, however, redwoods produce branches or sprouts that are entirely white. These sprouts cannot photosynthesize, stifling a redwood’s photosynthetic efficiency, because they have little to no chlorophyll (the pigment that gives foliage its green hue). They are called “albino redwoods” because of their lack of pigmentation and ghostly white appearance. They vary in size from a few inches to a few dozen feet in height and researches know of about 390 of them world-wide.

The first display of an albino branch was at the California Academy of Sciences August 1866 meeting. Those present noted that “no explanation or theory was offered to account for this curious, abnormal blanching of the foliage of a single species… not having been noticed… in any other species than the redwood.”

The first scientist who attempted to solve the mystery was George James Peirce, a plant physiologist from Stanford University. In 1898, he studied albino sprouts growing in the Santa Cruz Mountains near La Honda and Gilroy and determined that the needle anatomy and chemistry were slightly different from adjacent green tissues. Peirce also showed that the albino sprouts could not survive or be propagated on their own.

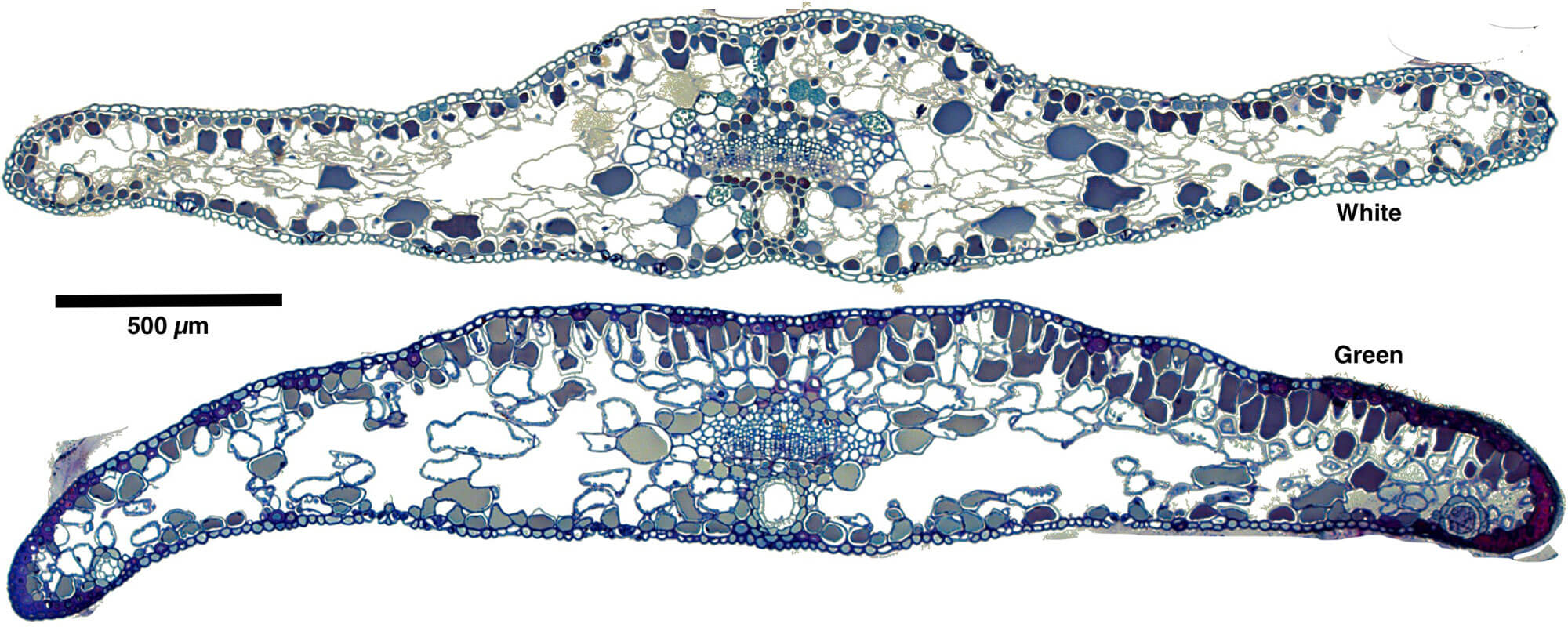

Cross section of La Honda white (top) and green (bottom) needle cell structure under a light microscope using a toluidine blue stain. Image by Zane Moore

Fast forward to the early 1960s, when Rudolf Becking, a Humboldt State University forestry professor, started working with albino redwoods. He conducted grafting experiments, attaching white branches to green rootstock, and attaching green branches to albino rootstock to see if the chlorophyll would travel from green shoot to white shoot. When the white foliage did not turn green, even after a few years, his experiments proved that albino redwoods are not a physiological phenomenon but rather a genetic one.

Studies of chimeric redwoods offer further understanding. A chimera is an organism that has two different genotypes—two sets of DNA—in one. In redwoods they occur with variegated foliage, half green and half white. Arborist Tom Stapleton first discovered a naturally occurring chimeric redwood in 1996. “Chimeras are basically like two trees in one,” Stapleton explains. Green tissues act as surrogates to the white ones, gathering the sun’s energy and sharing it with the white tissues. Redwoods are so efficient at photosynthesis that a green branch can provide enough food for a white one over five times its size.

So why do green redwoods keep these albino sprouts and trees alive and flourishing even though they are a drain on resources?

Remember Peirce’s tissue comparison study? In 2013, I expanded upon his experiment, both with the La Honda albino redwoods that were the focus of his experiment and trees from Santa Cruz and Sonoma counties. I tested the chemical compositions of the foliage and found that green needles were at the threshold of heavy metal toxicity (basically the equivalent of lead poisoning in humans). Adjacent white leaves, however, had more than double the toxic concentrations of the green leaves and were able to survive. In other words, the green leaves were at the point of dying, but the albino leaves sequestered and removed toxins saving the green leaves from a toxic demise.

Zane Moore is a Plant Biology Ph.D. student at U.C. Davis studying mutations in plant cells. He received his B.S. in Botany from Colorado State University. Zane is a California State Parks docent and researcher at Big Basin Redwoods State Park, where he discovered the tallest redwood on earth south of San Francisco (the location is a secret). Photo by Audrey Moore

Albino redwoods are nature’s beautiful toxic waste dumps. While there still isn’t a definitive cause to what initiates these mutations, research has found that there is a high proportion of albino redwoods in areas of high UV light exposure and increased human activity. Albino redwoods are a sign of amazing adaptability.

Often called “ghosts of the forest” due to their ghostly hue, albino redwoods literally cling to life—eternally ephemeral—sacrificing themselves for the good of the other trees around them in their endless struggle for existence.

Additional Information:

- Visit Zane Moore’s website at chimeraredwoods.com

- If you would like to report an albino redwood discovery or have related questions, please email Zane at albinoredwoods@gmail.com.

- Read this San Jose Mercury News article: Albino redwoods: Mystery of ‘ghosts of the forest’ may be solved

- Watch the following videos about albino redwoods from KQED Science: