A Tangled Web: Redwoods, Colonialism, Eugenics, and Climate Change

Mycelium is a root-like fungal network that is often unseen but a thimble of soil is estimated to contain 400 meters of mycelia threads, photo by Kirill Ignatyev

A Note from Sempervirens Fund: Dr. Patricia Ononiwu Kaishian's essay examines the rise of the redwoods conservation movement at the same time Eugenics was gaining prominence in America. We invite you to learn along with us about these tangled movements, their roots, and the consequences we are still overcoming together today. You can also join us February 28 "Under the Redwoods" for a conversation with the author about the essay and her work in mycology.

Unsound Science

Claiming to follow from Darwin’s new theory of natural selection, and operating within the context of an already racially stratified society, eugenicists used highly-dubious pseudoscientific studies to ascribe valued traits like strength, charisma, fortitude, and intellect to white European Americans and denigrate other racial groups as subhuman. These same logics were then used to create ecological hierarchies: certain species were assigned value based on what was biggest, oldest, and considered most charismatic. For some leaders and supporters of the redwood conservation movement, the logic of eugenics was used to uplift the superiority of redwoods.

by D. Nguyen

Destruction of an Environment and the Push for Its Conservation

by Mike Kahn

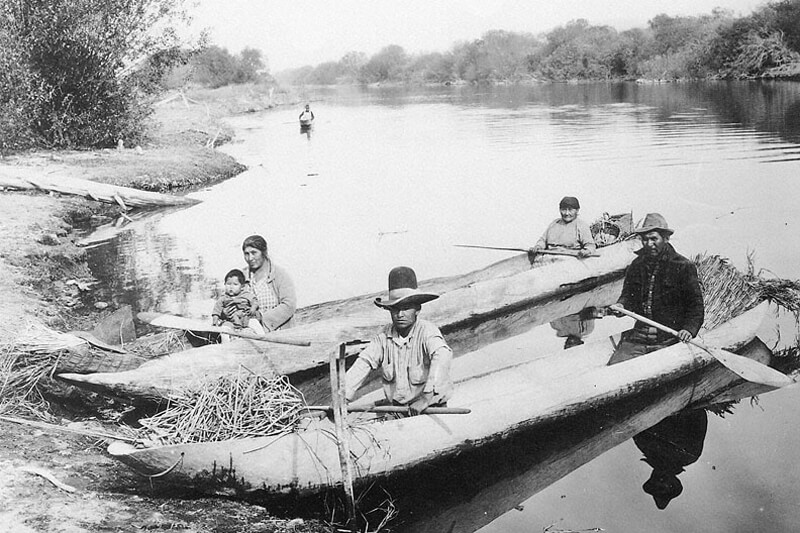

To understand why eugenicists sought to conserve the redwoods, we must first turn our attention to the history that imperiled them, that of settler colonialism in the United States—one that killed and displaced the Indigenous occupants and engaged in an extractive and destructive relationship with the land. For most of the last fifteen thousand years, the coast redwood trees — Sequoia sempervirens (coast redwood) and Sequoiadendron giganteum (giant redwood)— lived alongside Indigenous peoples including the Cahto, Chimariko, Esselen, Hupa, Karuk, Lassik, Mattole, Miwok, Mutsun, Nongatl, Pomo, Rumsen, Sinkyone, Tolowa, Wailaki, Wappo, Wiyot, and Yurok-speaking peoples. During this time, redwoods and humans were members of a dynamic and enduring ecological community. The redwoods provide material resources, both directly as wood for building, and as habitat for other plants, fungi, and animals, which in turn nourished and supported the human species.

Settler Colonialism

Cornell Law School’s Legal Information Institute defines settler colonialism as, “a system of oppression based on genocide and colonialism, that aims to displace a population of a nation (oftentimes indigenous people) and replace it with a new settler population. Settler colonialism finds its foundations on a system of power perpetuated by settlers that represses indigenous people’s rights and cultures by erasing it and replacing it by their own."

Deep Connection

Redwoods and associated species and habitats are also imbued with deep cultural and spiritual meaning. The trees were used to create ceremonial lodges, and ceremonies would also be performed when carefully taking the tree, as needed, from the land. Many who resided in these areas centered the landscape in their creation stories and cosmologies. The landscape is not simply the stage upon which the human character plays out the story of existence; rather, the landscape is the human story and vice versa. In his essay "The Ancient Ones", Chairman of the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, Greg Sarris, writes, “The landscape was our sacred text, and we listened to what it told us. Everywhere you looked there were stories.”

Klamath Indians on the Hoopa Reservation circa 1870-1900 in boast dugout from trunks—usually either redwood or pine.

Severed Ties

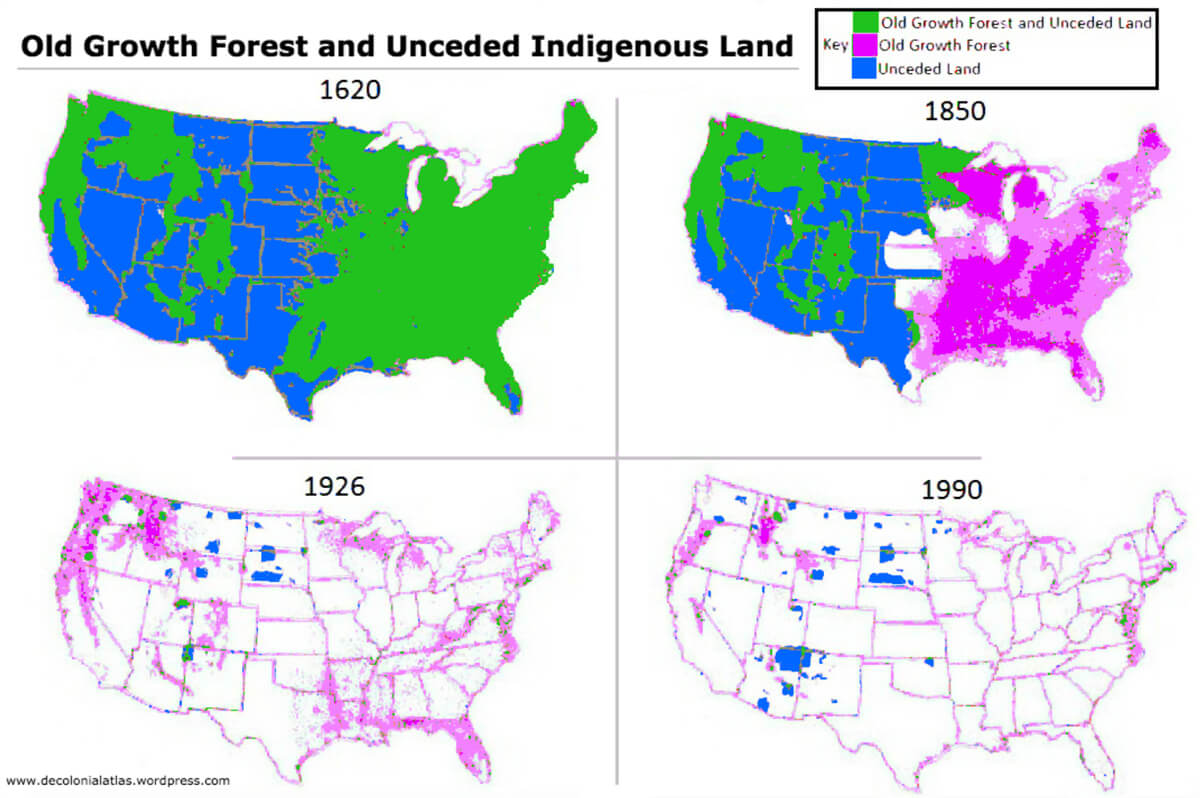

The project of American settler colonialism encouraged European and later American colonists to expand the American border westward. The ever-expanding frontier was facilitated by settling the land and extracting its resources. To do so, however, settlers often displaced and came into violent confrontations with the existing Indigenous inhabitants of the land, leading to one of the largest genocidal campaigns in recorded history.

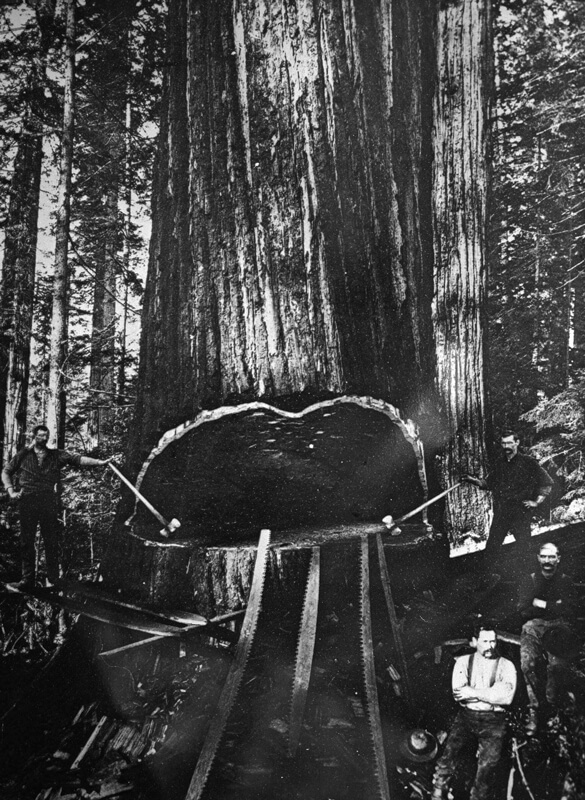

Redwood logging in the Santa Cruz mountains from our historic archive.

The reciprocal relationship between land, redwoods, and Indigenous peoples was dramatically altered following colonial westward expansion and the resultant genocide. The severing of ties between people, their nonhuman companions, and their ecological lifeways has led to generations of trauma for the relatively few who survived, as well as massive biodiversity loss — human and biodiversity plummeted in tandem. The dutiful stewards of ancient evolutionary relationships were replaced by often detached and naive extractivists looking to commodify the biology of redwoods and their affiliate species. The physical transformation of the land was tremendous—since the 1850s, 95% of the original redwood habitat has been cut at least once. What was once humming with ancient collaborations became barren, and what was not directly destroyed became stressed, dislocated, fragmented, and constantly threatened.

map by Jordan Engel, Decolonial Atlas

Birth of the Redwood Conservation Movement

The destruction of the redwood habitats was appalling to many Euro-American settlers, who rightfully recognized these habitats to be beautiful, irreplaceable, and in need of protection. The speed and scale at which redwoods (and many other habitats) were being razed catalyzed the organization of scientists and citizens in an effort to conserve them, heralding in the American conservation movement. Calls for the U.S. government to legislate preservation of certain habitats began around 1860, leading to a series of established parks and environmentally oriented groups. In 1872, Yellowstone National Park was the first established national park, a designation that protected this now famous landscape from destruction by European settlers. Founded in 1900, Sempervirens Club (now Sempervirens Fund) has since protected more than 54 square miles of redwood forest. Shortly after, in 1902, California’s first state park, Big Basin Redwoods, was established.

Sempervirens Club members orgnizing in the early 1900's, photo from the Sempervirens Fund archive

photo by Canopy Dynamics

These organizations and efforts were effective at halting redwood deforestation, raising awareness of the value of ecosystems, and contributing toward the contemporary framing of “environmentalism.” Real, tangible benefits to the earth came from these efforts, such as vast swaths of protected habitats, development of biodiversity monitoring protocols, advances in scientific research in ecology, and the return of species such as the peregrine falcon and the California condor from the brink of extinction.

However, like much of American history, a closer examination of the conservation movement reveals a more insidious dimension, one that is rarely discussed or acknowledged. In the effort of redwood conservation, a peculiar partnership was forged; for some redwood advocates, their conservation was not simply about protecting the land from destruction. Instead, as some of the world’s tallest and oldest trees, redwoods were considered the perfect symbol for the burgeoning American eugenics movement.

Eugenics and Race Science

Eugenics was a popular, widespread movement that was routinely taught in universities throughout the 19th and into the 20th century. Purportedly building off of Darwin’s new theory of natural selection, eugenicists engaged in both gene-sorting and genetic advocacy. First, they attempted to sort the world through scientific means into those species and races most fit, best adapted, and most evolved, in contrast to the maladapted, unfit, and least evolved. Second, they argued that the human gene pool could be made stronger and more evolved by eradicating its contaminating elements.

At base, however, the eugenics project was a thinly veiled attempt to use pseudo-scientific means to justify preexisting racial and class hierarchies. Using the language of genetics, eugenicists attempted to prove the biological nature of race, and tied it to racialized qualities, such as intellect, work ethic, poverty, and criminality. Eugenics ultimately sought to maintain social hierarchies, arguing for the superiority of the “Nordic race” (later expanding to include Europeans and whiteness more broadly), as well as hierarchies of ability, gender, and orientation. More specifically, its goal was to preserve certain genetic traits and behaviors that have been evaluated to be superior by European standards. This has been practiced through selective breeding (inbreeding), sterilization of groups deemed inferior, and through the construction of institutions that reinforce the dominance of particular groups over others.

Eugenics Tree image courtesy of American Philosophical Society. Eugenics poster on display at the Jewish Museum photo by Cameron Adams.

Eugenics: Purity and Prejudice

Central to eugenics is the notion of purity in genetic material or gene pools. The field was led by prominent scientists, such as Francis Galton (1822–1911), Karl Pearson (1857–1936), and the so-called “Father of Statistics,” Ronald Aylmer Fisher (1890–1962). And their political views were not marginalized, secretive, nor even arguably gray — Fisher, who served as the president of the British Genetical Society from 1940–1943, was in favor of sterilization of the “feeble minded.” Following the fall of the Third Reich, he wrote a letter appealing for the professional reintegration of the Nazi scientist Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer, who himself was a student of the notorious Nazi doctor, Josef Rudolf Mengele, known as the “Angel of Death.” In his letter he writes of the Nazis, “In spite of their prejudices I have no doubt also that the Party sincerely wished to benefit the German racial stock, especially by the elimination of manifest defectives” (Weiss, 2010).

The Idea of “Wilderness”

An unnamed old-growth redwood towers above the surrounding second-growth blanket of forest in Humboldt Redwoods State Park, by Michael Nichols, National Geographic

Eugenicists did not limit their genetic classification schemes to the human species but rather expanded its philosophy into the broader natural world. What was biggest, oldest, most charismatic was considered the best, and therefore most evolved. And having already categorized white people as the most evolved specimen of their respective species, eugenicists imagined common cause in preserving other examples of evolutionary dominance—the tallest trees, the soaring eagles, the highest mountain peaks. The very idea of wilderness was born out of the eugenics-influenced American conservation movement, where the polarized values of this philosophy could be applied to the landscape. Eugenicists feared the pristine character of the white race was sullied by mixing with inferior races, and, like the redwoods, was at risk for total extinction. Galvanized by this symbology, prominent eugenicists—such as Theodore Roosevelt, Madison Grant, and Charles M. Goethe—organized groups to advocate for the redwood forests, and laid the foundation for the mainstream conservation movement in the United States (Allen, 2013).

Like the imagined purity of white genes, the chosen species and the pristine wilderness they inhabited were to be protected from the crudeness of humanity. The protection of the more homely habitats like grassland prairies or the lowly species of mushrooms have not been prioritized because they were seen as expendable.

The Impediment of Purity

In the eugenicists' worldview, there are three linked principles: 1) humans are exceptional in nature in all respects as the pinnacle of creation or evolution; 2) the white race is exceptional among all other races; 3) a thriving society is achieved and maintained by oppression of both inferior races and groups of people, and of nature. For eugenicists, societal breakdown can be explained by impurities in the gene pool, as opposed to an unequal social infrastructure, and this flawed logic applied to eugenicists' approach to conservation. Instead of correctly identifying the cause of the destruction of redwoods–settler colonialism, the genocide of Indigenous peoples and loss of their ecological knowledge, and extractive industry–American eugenicists likened the decimation of trees and the spoiling of habitat to their perceived erosion of the white race.

This purity mindset, which refuses to acknowledge the root cause of the crisis we are in, has impeded our understanding of the entangled ecological realities of our own societies and bodies as well as the ecological systems that support the human species. In addition to the enormous human cost of such racist ideologies, there have been profound costs to our biodiversity. For the eugenicists, as well as for cultures influenced by its oppressive dogma, there is a great humiliation in recognizing the shared realities and interdependencies between races and between species. In order to adequately respond to the threat facing climate, and redwoods, we must get to the roots.

Loggers in the process of cutting down a large old-growth redwood in the Santa Cruz mountains from the Sempervirens Fund historic archive.

The Roots: A Deeper Understanding of Climate Change

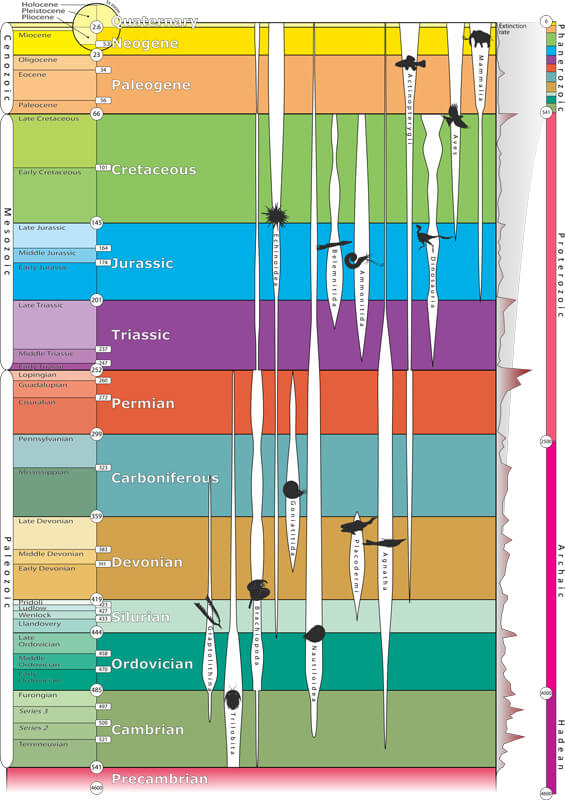

Geologic time scale by Frederik Lerouge.

Scholars of the humanities and the sciences introduced and popularized the term anthropocene to describe this epoch of geological and planetary affairs. Like other geological epochs—e.g., the Pleistocene, which includes the most recent glacial period—the anthropocene is describing a period of time that is characterized by specific forces or events. In this case, the root “anthro” is referring to the widespread impacts the human species has on the earth. This term is useful in emphasizing that climate change (formerly referred to as “global warming”) is the result of specific human behaviors, such as burning fossil fuels. As opposed to other geological epochs that occur without human involvement and typically over tens of thousands of years or more, many of the changes occurring within the anthropocene are detectable within a human life span. It is this tremendous compression of time that jeopardizes so much biodiversity, and thus the web of interactions that supports our own species.

Anthropocene

National Geographic defines the Anthropocene Epoch as "an unofficial unit of geologic time, used to describe the most recent period in Earth’s history when human activity started to have a significant impact on the planet’s climate and ecosystems."

Plunder of the Plantationocene

But some scholars have noted that the term anthropocene has the tendency to obscure critical aspects of our present situation. For it is not all humans that are the problem — it is how some humans have plundered the earth, hoarded wealth, and relied upon the eradication, displacement, or enslavement of other humans and species. Feminist philosophers Donna Haraway and Anna Tsing, among others, have instead utilized the term plantationocene, with the root word “plantation” referring to the style of agriculture first made possible through the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. Through the ghastly horrors of chattel slavery, industrial farming took shape. Primarily West Africans were ripped from their ecological birthrights and deposited into wholly unfamiliar ecologies in lands cleansed of Indigenous inhabitants, and for generations they were forced to labor in the mass production of capital.

Imprinting the Earth

Industrial farming like the expansive rows of monoculture seen here, took shape from plantation style agriculture made possible through slave labor, photo by Jeremy Buckingham

This is where social and biological histories become entangled in such a way that literally imprints the earth. For the creation of plantations we see the razing of forests and decimation of grasslands at dizzying scales. We see the formation of large-scale monocultures, in which a single species is grown en masse and then stripped from their ecological birthrights. Designed for maximum profit, the enslaved laborer is forced to tend to these monocultures in daily, grueling repetitions, a task that no person could conceivably carry out absent the threat of death or torture.

The Effects of Forced Farming

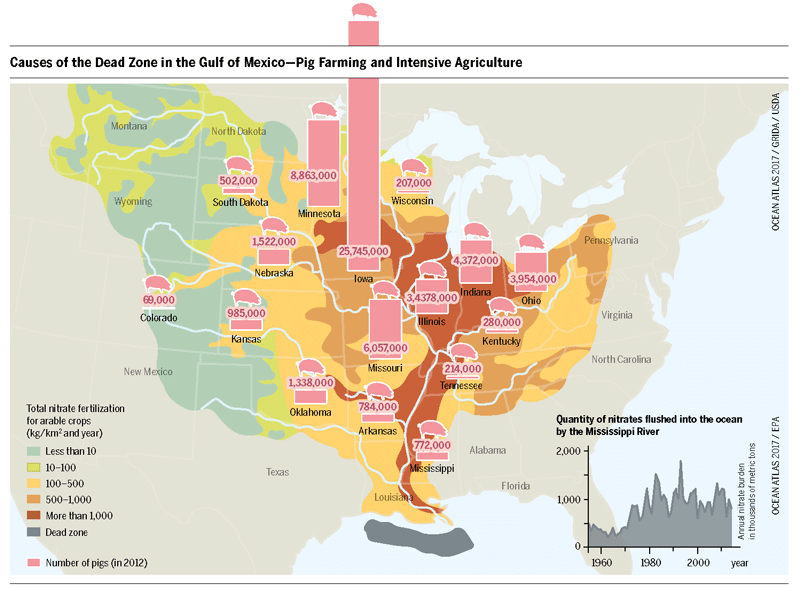

by Heinrich Boll Foundation University Of Kiels Future Ocean Cluster Of Excellence, Ocean Atlas.

In these plantations, plants and animals are forced into conditions in which they did not evolve, and therefore require costly and monumental interventions to be kept alive, such as re-routing entire rivers, and massive fertilizer inputs. Enormous amounts of runoff from these farms enter waterways around the world, including the Mississippi River, which feeds into the Gulf of Mexico, creating the world’s largest marine dead zone, an area of minimal biodiversity, due to fertilizer-induced algal blooms and their cascade effects. Being ripped out of their ecological communities, industrial farmed species are made more vulnerable to pathogens, often fungi. This then leads to more interventions—slurries of pesticides, insecticides, fungicides, and antibiotics—many of which have severe nontarget effects and are poisonous to bodies in ways we are just now realizing.

Colonialism and the Loss of Biodiversity

Around the world, colonialism leads to biodiversity loss, in large part because of the introduction of industrial agriculture and the simultaneous eradication of peoples who so dutifully cared for their companion species. These methods are sustained because they are lucrative businesses that have led to massive accumulations of wealth for certain individuals and nation states; entire nations have been built on sugar, corn, chocolate, bananas, coffee, and other species. The true cost of these methods have been invisibilized by those in power.

Our Social History IS The Climate Crisis

What we refer to as climate change is not simply an equation of carbon parts per million in our atmosphere. Nor is climate change about how many billions of trees should be planted, nor about rote phrases like “save the Amazon.” To fully understand this crisis, we must understand the forces that brought about its possibility—both natural and social histories of our earth, including the deadly and extractive history of settler colonialism in the United States. These social realities are not coincidental to the climate crisis: they are inextricably linked; they are the climate crisis. In order to address the climate crisis, we must reckon with how these legacies continue to influence the field of conservation to this day.

Decomposing and Myceliating the Legacy of Eugenics

photo of painting in Sempervirens Fund's historic archive

A deadly combination of habitat destruction, drought, super storms, mega-fires, and more continue to threaten our precious redwoods, as well as most habitats around the world. As we struggle against the enormity of the forces described above, we must consider how conservation efforts that valorize and privilege particular species, like redwoods, without accounting for the seemingly less charismatic elements of an ecosystem, like fungi, does so at their peril. When we advocate for the less charismatic species and habitats, we help recalibrate the values of our society. In fact, turning our attention to these “lesser” elements teaches us to grapple with these complex histories.

Myceliation

mycelium in soil, photo by Kirill Ignatyev

A largely invisible network of fungal cells, called mycelium, is critical to the functioning of our planet. Yet conservationists have paid scant attention to these complicated and essential networks, favoring instead the charismatic giants that they help to support. If we want to begin myceliating the legacy of eugenics in conservation, we must become aware of the invisible, interconnections tying that dark history to the species that have been deemed worthy of protection. It is only through interrogating the hierarchies of the conservation movement that we can begin to uproot the logic of eugenics. To do so means paying attention to the organisms that are seen as inconsequential as a result of this lens, and to be aware of the history that got us here. The more we learn about fungi, the more we realize how critical they are to the ecosystems that we seek to protect. While a eugenicist lens focuses on the redwood tree as the tallest and most glorious specimen of the forest, removing that lens reveals the enormous ecological scale of less visible organisms.

What Redwoods Need

Redwoods don't become the tallest trees on Earth alone. Here are just some of the important things they need to reach great heights and ages.

Fog by F. Balthis; Coral Fungus by Ken-Ichi Ueda; Coho salmon by Bureau Of Land Managementby; Roots by Rudydale

Decomposition is key to the role that fungi play in an ecosystem and critical to the symbiotic interactions they perform—ranging from parasitism to mutualism—all of which is essential to the biodiversity of habitats around the world. Likewise, myceliating the conservation movement requires that we decompose the harmful legacies of eugenics and settler colonialism, and attend to the ways they have continued to invisibly shape our relationship to land stewardship. In addition to being fully transparent about the history of redwood conservation, committing to myceliating and decomposing the harmful legacy of eugenics would look like: 1) supporting tribal sovereignty on the lands we now call home; 2) committing to seeing all biodiversity as worthy of human care and consideration; 3) including explicit protections for fungi and other non-charismatic and/or historically neglected organisms in our conservation frameworks.

Potentially mistaken for "scat", a pile of wild animal feces, this fungi called "cramp balls" (Annulohypoxylon thouarsianum) decays wood so there is room for new tress and other species, by M. Kahn

Profound Impurity

An estimated 8% of human DNA is thought to be comprised of embeded viruses

Eugenics is not only morally wrong, it has impeded our scientific understandings of the natural world. Just as white people are not biologically superior to any other race, humans are not inherently “more evolved” than other species. As humans, we evolved within and amongst a consortium of other organisms—bacteria, fungi, plants, and other animals—some of whom have been thriving on this planet for millions if not billions of years prior to our emergence. While it is true that certain traits in human anatomy have gone through more change than those of our closest ancestors, there are many metrics by which we can define evolutionary success, including, paradoxically, the least amount of change. The forces of evolution are not moving toward any predetermined direction.

Indeed, in our very DNA, we can trace lines to bacterial ancestors; lodged in our genetic code are viruses that have embedded themselves over millennia. Our DNA is a call and response to the world around us, a multispecies story; we are profoundly impure. From the macro to the micro, it is these impurities that have allowed us to thrive for millennia.

More to Explore

- Read more about the redwood forests’ Underground Allies

- Read more about the impacts of the forced removal of Indigenous peoples and California’s colonization on forests and fires in The Past, Present, and Future of Fire and Stewardship

- Read about Our Commitment to Diversity Inclusion Equity and Justice

Sources

Interested in digging a little deeper into the entanglement of eugenics and redwood conservation? Here are some sources with more information indicated in the story above:

Allen, GE. “Culling the Herd: Eugenics and the Conservation Movement in the United States, 1900-1940.” Journal of the History of Biology, Volume 46(1), 2013, Pages 31–72, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10739-011-9317-1.

Madley, B. “Reexamining the American Genocide Debate: Meaning, Historiography, and New Methods.” The American Historical Review, Volume 120(1), 2015, Pages 98-139, https://academic.oup.com/ahr/article/120/1/98/47185.

Weiss, SF. "After the Fall: Political Whitewashing, Professional Posturing, and Personal Refashioning in the Postwar Career of Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer”. Isis, 2010, Volume 101(4), Pages 722–758, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/657474.