Fungi of the Forest: Meet the Mushrooms of San Vicente Redwoods

All photos and video by Orenda Randuch Photography

Notes on Mushroom Identification

Hundreds of fungi are known to exist in the redwoods but there are an estimated 3 million species of fungi on the planet and only about 140,000 of those have been described by science. Even those that have been described are sometimes re-classified, like the mica cap, as we learn more about them. Pictures can’t always give us all of the information needed to properly identify a mushroom, like yellow staining milk caps and southern candy caps which could look similar from above at different stages. Seeing a mushroom from below, like its gills, or inside, like the center of its stipe, can help but sometimes spore color–which can require time or a microscope–are needed to be sure, Maya notes.

Mushroom cap

Mushroom cap and stipe shape

Mushroom stipe base and gills

Mushroom stipe center

What is a Mushroom?

You may think of mushrooms as food, medicine, or psychedelics but to fungi mushrooms are reproductive organs. When you consume a mushroom, you are only consuming the fruiting body of a much larger organism. “The body of the fungus is mycelium, which is a filamentous network made up of microscopic strands called hyphae,” Maya explains. A mushroom’s role is to share its genetic information to create the next generation. The reason we see mushrooms while most of the fungus is underneath the soil, is because a mushroom rises up to where it can spread its spores on the wind or with the help of passersby.

Brown Cup Mushroom

Brown cup mushrooms (Peziza arvernensis), like these found recycling wood to enrich the soil at San Vicente Redwoods, release spores from the smooth inner surface of their cup in a delicate smoke-like wisp after its been triggered by touch or a burst of air. Maya suggests blowing on a cup mushroom with a long stream of air to see its spores dance gently away. It takes billions of spores to be visible to the human eye, Maya shares, each one of those spores contains genetic information to create the next generation of fungi.

Brown cup mushrooms

Spore Color

The color of spores can be a helpful way to confirm the identity of mushrooms like Pholiota velaglutinosa that have look-alikes with similar habitats like other fungi in the Pholiota family. Spores are tiny but a mushroom’s gills are designed to pack as many in as possible. The best way to see a mushroom’s spore color is to place the mushroom in question on a plain white sheet of paper and covering it with a bowl to see the color of the spores as they collect on the paper, Maya suggests. Pholiota velaglutinosa has brown spores. Another helpful clue for confirming Pholiota velaglutinosa, also known as the slimy-veiled Pholiota, is the thick slimy coat on the reddish brown cap when it's fresh.

Pholiota velaglutinosa mushroom

The Dangers of Decay

While many fungi help to decay wood and dead plant matter–creating space and nutrients for the next generation–a mushroom’s own decay can make it difficult to properly identify. Even past its prime, this large mushroom felt nearly as heavy as the wood it was growing on. But Maya cautions, decay can effect identifying features of mushrooms—some are even known to have their flesh change color when bruised or cut. This specimen is decayed enough that Maya isn’t confident of its identity.

Violet Tooth

Rarely seen in the Santa Cruz mountains or on conifers–trees that make cones–this violet tooth (Trichaptum biforme) was found helpfully breaking down the wood of a burned Douglas-fir at San Vicente Redwoods. It’s violet edge helps differentiate it from the more common turkey tail (Trametes versicolor) but the color can fade as the mushroom ages.

Violet tooth mushroom

Rosy Conk

Another colorful soon to be fan-shaped fungi decomposing a scorched fallen Douglas-fir is the rosy conk (Rhodofomes cajanderi). When young, the rosy conk can be hoof shaped like these. Look closely and you may see what appear to be drops of blood but don’t worry, the reddish droplets are enzymes the mushrooms release.

Mica cap mushroom

Mica Cap

While foraging isn’t permitted in San Vicente Redwoods fragile recovering ecosystem, this common edible mushroom can be found growing in clusters near the stumps, dead trees, and logs that it breaks down from fall into spring throughout the redwood range. Mica cap (Coprinus micaceus, formerly known as Coprinus micaceus until 2001) doesn’t have much flesh but can be used to make flavorful sauces and gravies. One of their easiest identifying features is its deliquescing gills which means they release their spores in an inky liquid.

Copy Caps

Yellow staining milk cap (Lactarius xanthogalactus) can be found growing from southern California to Oregon where these mycorrhizal fungi network with the roots of trees to exchange nutrients and information. But this yellow staining milk cap was seen growing at San Vicente Redwoods where it has a look-alike. Maya explains yellow staining milk cap isn’t edible and can give you a tummy ache while its similar looking cousin southern candy cap (Lactarius rufulus) is edible. Her bonus tip? She likes to place southern candy caps on the dashboard of her car and enjoy their maple syrupy smell as they dry like a natural air freshener before cooking with them. Southern candy caps grow and partner with coast live oaks and so will yellow staining milk caps. Maya says the best way to make sure you don’t have a yellow staining milk cap is to look for their namesake yellow milk-like substance that they lactate.

Southern candy cap mushroom

Southern candy cap mushroom

Yellow staining milk cap mushroom

Yellow staining milk cap mushroom

Confusing these cap mushrooms is a mistake you can certainly survive to regret. However, there are three mushrooms in the Santa Cruz mountains that Maya says it could be possible not to survive misidentifying.

Poisonous Mushrooms and Mistaken Identity

Despite common misconceptions of deadly mushrooms, Maya says you can touch or take the tiniest bite of any mushroom and you’ll be fine. However, the three most common deadly poisonous mushrooms in the Santa Cruz mountains—death cap (Amanita phalloides), deadly galerina (Galerina marginata), and western destroying angel (Amanita ocreata)—can easily be mistaken for other mushrooms and consumed in dangerous amounts.

Destroying Angel

Thankfully, a western destroying angel (Amanita ocreata) can be identified by its white gills, wide bulbous volva (sack) at the base of of its stipe, and tough stipe that is not hollow, Maya explains. A stipe is what us non-mycologists might think of as a stem or stalk. Young western destroying angel mushrooms start out in white egg shapes that look a lot like edible puffball mushrooms. When foraging, Maya highly recommends slicing any puffball mushrooms in half to look for signs of a mushroom growing inside, like a stipe and cap, which could indicate it's actually an “egg” of a young western destroying angel.

Western destroying angel mushroom

Orange Jelly versus Witch’s butter

Orange jelly fungi can look alot like witch’s butter. While both are edible, by most accounts neither is terribly appealing once cooked and Maya advises against eating raw mushrooms. Raw mushrooms can have brown garden slug slime on them which can carry a disease, and all mushrooms contain chitin which–fun fact–gives them their rigidity just like insect and crustacean exoskeletons and can give us tummy troubles. Orange jellies are more orange and less “snotty” than witch’s butter but unless you have them side by side, the easiest way to tell them apart is by what they’re growing on. “A lot of mushroom identification is rotting log identification,” Maya laughs. This orange jelly spot (Dacrymyces chrysospermus) was found growing on a Douglas-fir which makes cones whereas witch’s butter (Tremella aurantia) is a parasitic fungus that grows on false turkey tail fungi on broad-leaved trees like oaks.

Orange spot jelly mushroom

Orange spot jelly mushroom

Witch's butter mushroom

False Turkey Tail

and Sudden Oak Death

Unlike turkey tail (Trametes versicolor), false turkey tail (Stereum hirsutum) never has the solid white pore surface underneath that turkey tail does. But of course, its not always so simple to identify. While false turkey tail is usually seen in fan shapes you might expect of turkey tails, they can also make crust-like formations. False turkey tail is the most common mushroom in the Santa Cruz mountains, Maya says. Unfortunately, each false turkey tail seen growing on an oak or tan oak tree is a sign that the tree might be infected with Sudden Oak Death, she explains. While false turkey tails decompose the wood of trees including those killed by the invasive, quick spreading disease, the number of trees dying adds to the amount of wood that can fuel the next wildfire to more damaging levels. Although Sudden Oak Death can increase the spread of fire, fire can decrease the spread of Sudden Oak Death. Maya says, “good fire dramatically reduces Sudden Oak Death.”

Fire can also support fungi that support the trees and the future.

False turkey tail mushrooms

High severity burn area at San Vicente Redwoods

Fungi and Fire

From the trail, Maya points out how much better the forest fared where techniques based on traditional tending practices like prescribed burns and shaded fuel breaks were done before the CZU Fire tore through San Vicente Redwoods in 2020. “Burning practices that care for the oak trees also tend the fungi under the trees that benefit the oaks too,” she explains.

Mycorrhizal fungi that create a network for exchanging nutrients and information among trees in the forest benefit from low intensity fires like prescribed and cultural burns. Low intensity fires recycle the nutrients from dead branches, leaves and plant material into the soil where their tree partners can access them. Burning off that debris also reduces fuel the next wildfire can burn to grow hotter, faster and more damaging to mycorrhizal fungi’s forest friends.

Less severe burn area at San Vicente Redwoods

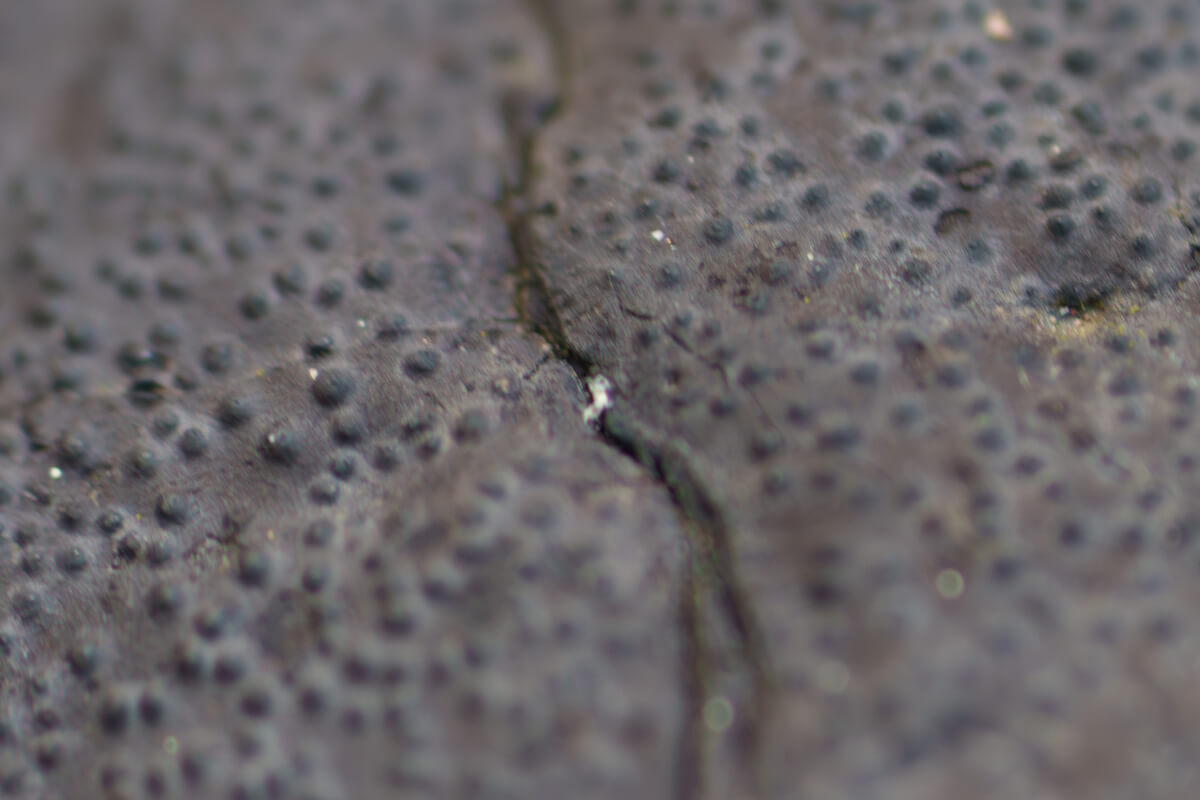

Biscogniauxia

Upon first glance, you may think Biscogniauxia is wood charred in a fire, but it is actually a fungus that Maya has only seen post-fire. This possible fire mimicry may just be a coincidence, but to tell whether you are looking at burnt wood or a fungi working to break down wood after a fire, look closely for tiny dots which release spores.

“Fires break down nutrients in the summer, fungi break them down in the winter,” Maya explains.

Biscogniauxia fungi

Coltricia perennis mushrooms

Coltricia Perennis

Although much more could be learned about Coltricia perennis, sometimes called brown funnel polypore, it is known to have a preference for burned areas like San Vicente Redwoods. More than one fungi species currently uses the name Coltricia perennis but they are all different than most other small polypores. Coltricia perennis is ectomycorrhizal and forms helpful connections with coniferous trees in the redwood forest–especially pines–helping them to access nutrients and information rather than decay wood as many small polypores do.

Sulfur Tuft

Colorful sulfur tuft mushrooms (Hypholoma fasciculare) like these yellowish orange ones have been used for dye but Maya advises against using it for cooking. Sulfur tuft can cause what she politely calls “gastrointestinal discomfort”. Like other saprotrophic fungi, sulfur tuft has a crucial role in the forest. It mostly grows on Douglas-fir trees in the Santa Cruz mountains where it breaks down dead, woody debris and returns the nutrients to the soil. After the CZU Fire burned most of San Vicente Redwoods, there is lots of woody debris that would be beneficial to break down before it can become firewood for the next wildfire.

Sulfur tuft mushrooms

Fungi and the Future

The vast amount of woody debris that could fuel the next fire isn’t the only issue fungi can help with at San Vicente Redwoods. Maya shares that oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) are being studied at San Vicente Redwoods to see how they can help reduce further impacts from the CZU Fire on the environment. Oyster mushrooms are known for their ability to break many toxins down through their mycelium underground. By breaking down buried logs underground, Maya hopes oyster mushrooms can keep more of the carbon San Vicente’s trees had trapped out of the air. Near the creek, Maya hopes their mycelium, which act as underground sponges helping trees through droughts, can filter toxins from burned homes from washing into San Vicente Creek’s crucial habitat for endangered coho salmon and threatened steelhead trout. Fungi can even break down organic materials in petroleum and are being utilized to help clean up oil spills. However, as fungi help clean the environment around them, heavy metals can concentrate in their mushrooms, so Maya advises not picking mushrooms near a gas station or a road.

Oyster mushrooms

More Mushrooms

Are you eager for more mushrooms?

Join Maya Under the Redwoods

Want to learn more about how fungi offer nature-based solutions for human impacts like floods, fires, and climate change? Join Maya Elson for a free Under the Redwoods webinar on February 27th from 1- 2 pm Pacific.

Take A Hike

You can follow in Maya and Orenda’s footsteps by taking the mâ-rŭs trail to Vista Point and hai-mĭn’ trail back when you visit San Vicente Redwoods to see if you can spot the mushrooms above.

A Few Guidelines

- Please stay on the trail. Like tree roots, fungal mycelium networks underground can be damaged by our weight above ground.

- Please do not forage. Foraging is not permitted at San Vicente Redwoods to protect fragile and recovering ecosystems that have already suffered many human impacts.

- This is not intended to be a foraging guide, and Maya notes the challenges that similar looking fungi species can present even to mycologists in identifying. If you are interested in foraging, please consider reaching out to a professional guide. Maya leads fungi foraging hikes and mycology workshops with Mycopsychology Experiences.

Stay Tuned for Shrooms

Maya and her UC Santa Cruz students are beginning to survey fungi at San Vicente Redwoods. We look forward to finding out about more fungi species at San Vicente Redwoods from the class’ research visits. If you want to be the first to what about more fungi found on properties you help protect and care for, you can sign up for email here.

Fungi Photos

As Maya points out, mushrooms can be very difficult to identify from photos, even for experts. While we worked closely with mycologist and researcher Maya Elson in the field and on this guide to provide you with helpful tips to get to know mushrooms at San Vicente Redwoods, there are many fungi yet to be described by science and ever evolving species. If you think a mushroom above has been misidentified, let us know.

More to Explore

- Learn more about Fires, Floods and Fungi in the Forest with Maya Under the Redwoods

- Visit San Vicente Redwoods to see if you can spot any of the mushrooms

- Read more about how fungi are the forest’s Underground Allies