Nature Needs Time to Heal

When Will the Forest Rebound?

To find out, I called up Zane Moore, a redwood ecologist who’s pursuing a PhD at UC Davis. Since 2012, his search for the tallest trees in the Santa Cruz Mountains has taken him on foot up every creek and along almost every ridge within the 18,000-acre state park, which is within the ancestral territory of the Cotoni and Quiroste people, among others. Since the CZU fires died down enough to make it—if not safe, exactly, then at least not obviously lethally dangerous—to return, Moore has been among the dozens of researchers who’ve driven and hiked through the burn, recording the damage, and bearing early witness to the recovery.

Based on data from tree rings and analyzing fire damage in other old growth stands throughout the redwoods’ range, Moore estimates that the CZU fire was a once-in-a-millennium event. “I don’t think this fire is unprecedented for California’s redwoods—and there’s evidence of fires even worse than this,” he says. “But I think it’s been very rare.” Still, from what he’s seen in the forest since last August, and what he knows about the trees’ abilities to withstand fire, he estimates 98 percent of Big Basin’s redwoods will survive.

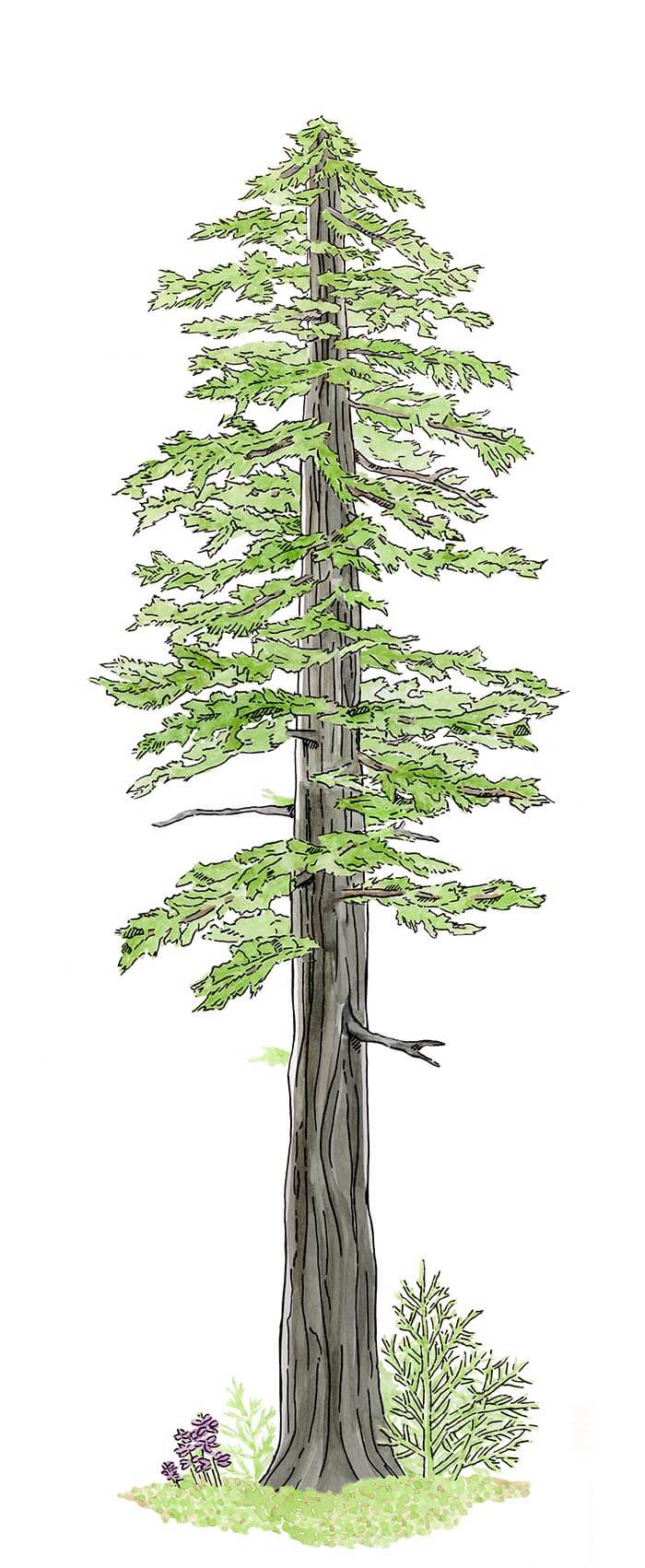

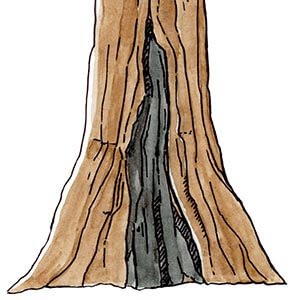

Thinking of those charred trunks I’d seen in the news, the first thing I wanted to know was: how long until Big Basin’s redwoods are, well, red again? “As the tree grows, those black parts will get sloughed off,” Moore said. In 20 years, he reckons the trunks will be about half red again. In 40 years, just a few scarred furrows will remain. “Anytime you’re in an old growth stand, you’ll see scars from past fires. They never necessarily get rid of all of it,” Moore says.

Moore is sanguine about the forest’s future—but for California’s human residents there’s not much cause for optimism in the wake of the CZU fires, which claimed one life, caused one injury, and forced 77,000 people to evacuate.

Before firefighters contained the blaze on September 22, it burned 86,000 acres and destroyed 1,500 buildings. The fire also burned 73 percent of the old growth redwoods remaining in the Santa Cruz Mountains, including much of Big Basin’s 4,400 acres of old growth. Fanned by strong winds on the third day of the blaze, fueled by hot air and drought-dried timber, the flames leapt to the tops of some of the park’s tallest redwoods. Almost every building, dozens of bridges, and hundreds of miles of roads and trails with Big Basin were destroyed or severely damaged. On August 20, Sempervirens Fund issued a statement that read, in part, “We are devastated to report that Big Basin, as we have known it, loved it, and cherished it for generations, is gone.”

That’s true enough. It’ll be the work of years, and the spending of many millions of dollars, to rebuild the infrastructure that makes this place accessible to its adoring public. And several of the park’s biggest and most beloved trees were killed by the fire and have fallen, or likely will soon. In a talk for the Santa Cruz Museum of Natural History in May, Moore ran through a partial roll call of possible casualties, including the Washington, Santa Clara, and Father of the Forest trees. Subsequent visits bring mixed news: “The Washington and Santa Clara Trees—could go either way … the Father of the Forest, I think has a chance.” The top 100 feet of the region’s largest tree has since snapped off, “so it’s no longer the largest.” The fire also toppled the widest tree in the Santa Cruz Mountains, “and it took out a few trees next to it, which is a bummer,” Moore said. Meanwhile much of Big Basin is still a fantastically hazardous place to be—partly because fire-damaged trees could come crashing down at any time, and partly because some areas are still on fire. Much of the park is closed to the public indefinitely. (The coastal portion at Rancho del Oso reopened in late May.)

Today just five percent of California’s old growth redwood forests remain. I think that’s partly why so many trees in Big Basin are named, known, and loved in the first place: Thousand-year-old trees are rare enough that each one felled by fire can seem like an unbearable loss. So it was heartening to spend an hour on the phone with Joanne Kerbavaz, an environmental scientist with California State Parks. “What I’ve been telling people is that we expect 90 percent of the redwoods to survive,” she said right off the bat. The figure comes in part from a 2014 paper in the journal Fire Ecology that studied tree mortality in the Santa Cruz Mountains following fires in 2008. She’s also taking clues from the fire scars that marked most of the park’s oldest trees, even before last August. “When you look at how much damage the old growth trees already had, and they’re still standing after a thousand or two thousand years,” she says. “Last year’s fires were, for most of them, another round of what they experienced before, rather than being something that’s more than they can withstand.”

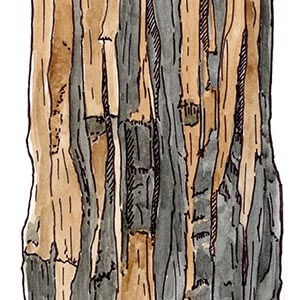

And when it comes to fire, redwoods can withstand a lot. Their thick, spongy bark insulates the wood, and even their eponymous hue is an adaptation to fire, the result of tannins in their bark. When the bark burns, Moore says, the tannins char quickly, but resist combustion—basically forming a shield that prevents the fire from burning into the tree’s more fragile interior.

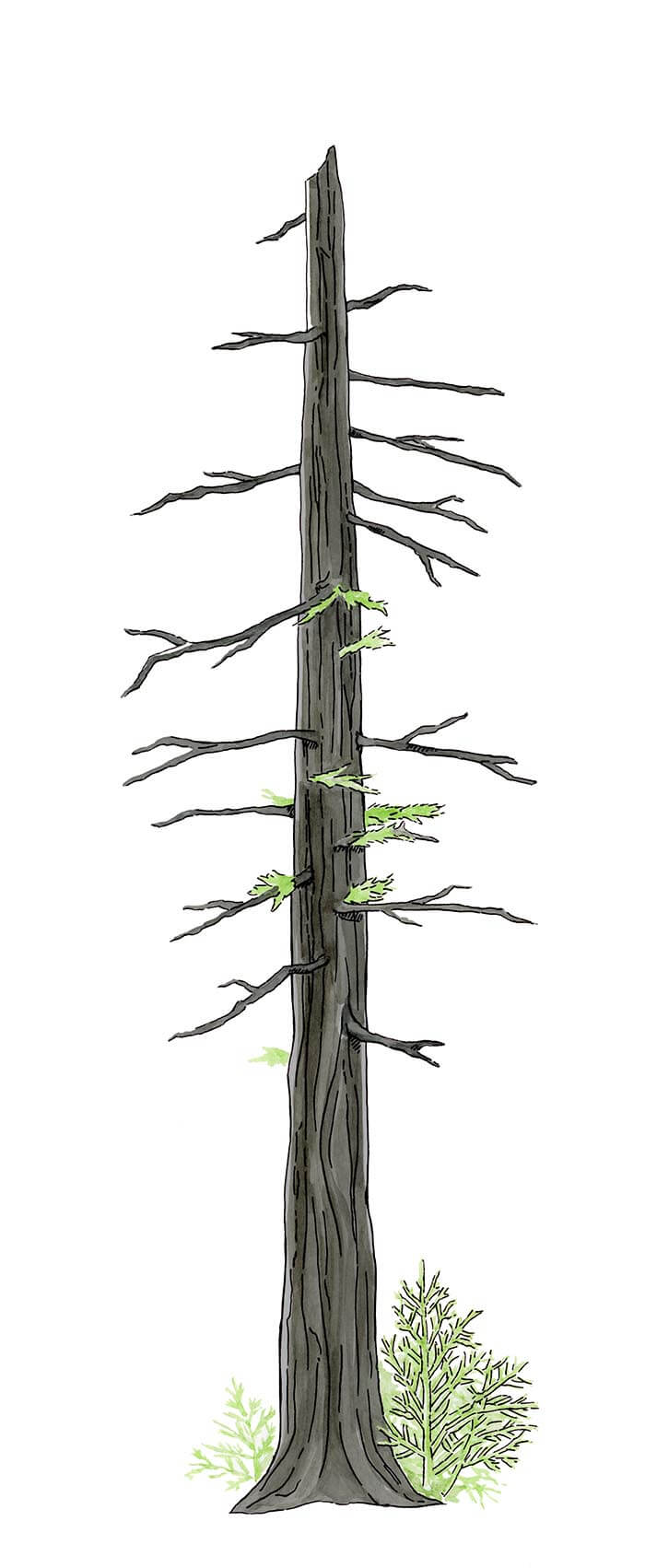

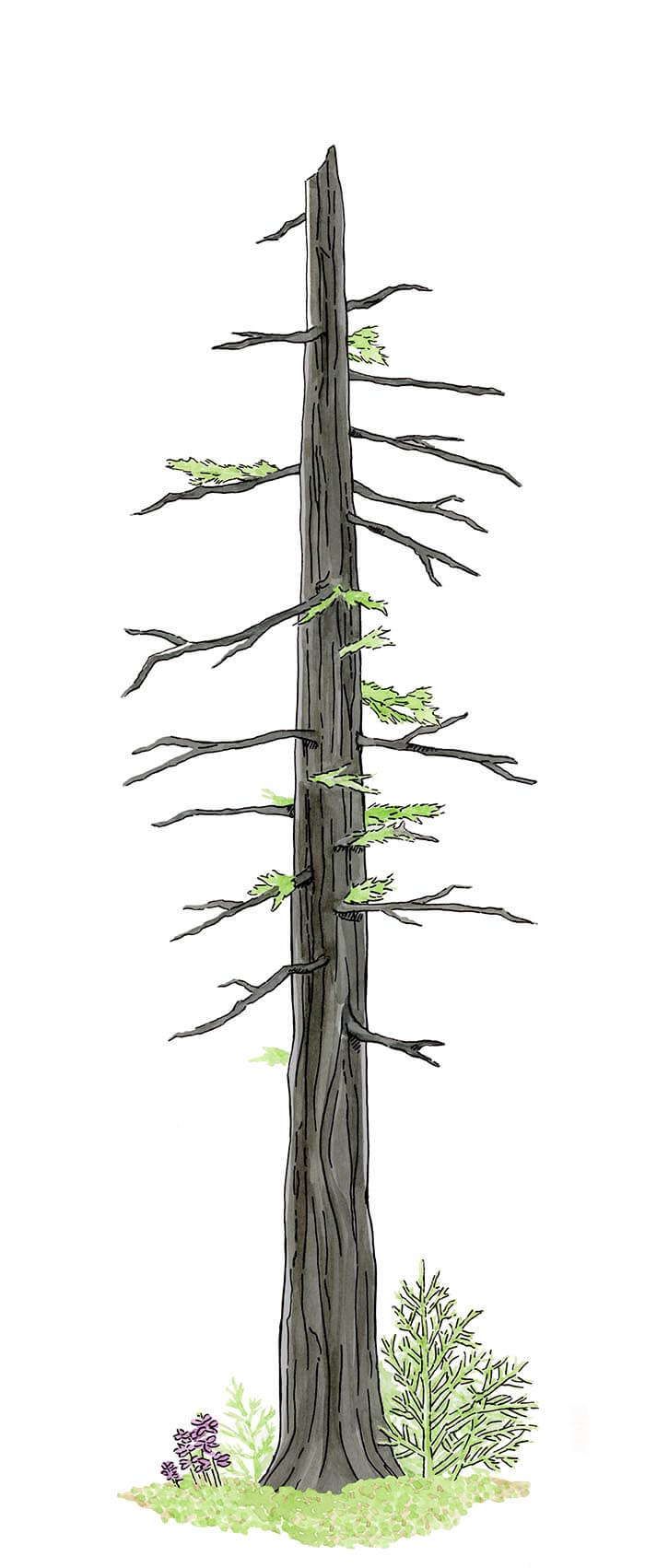

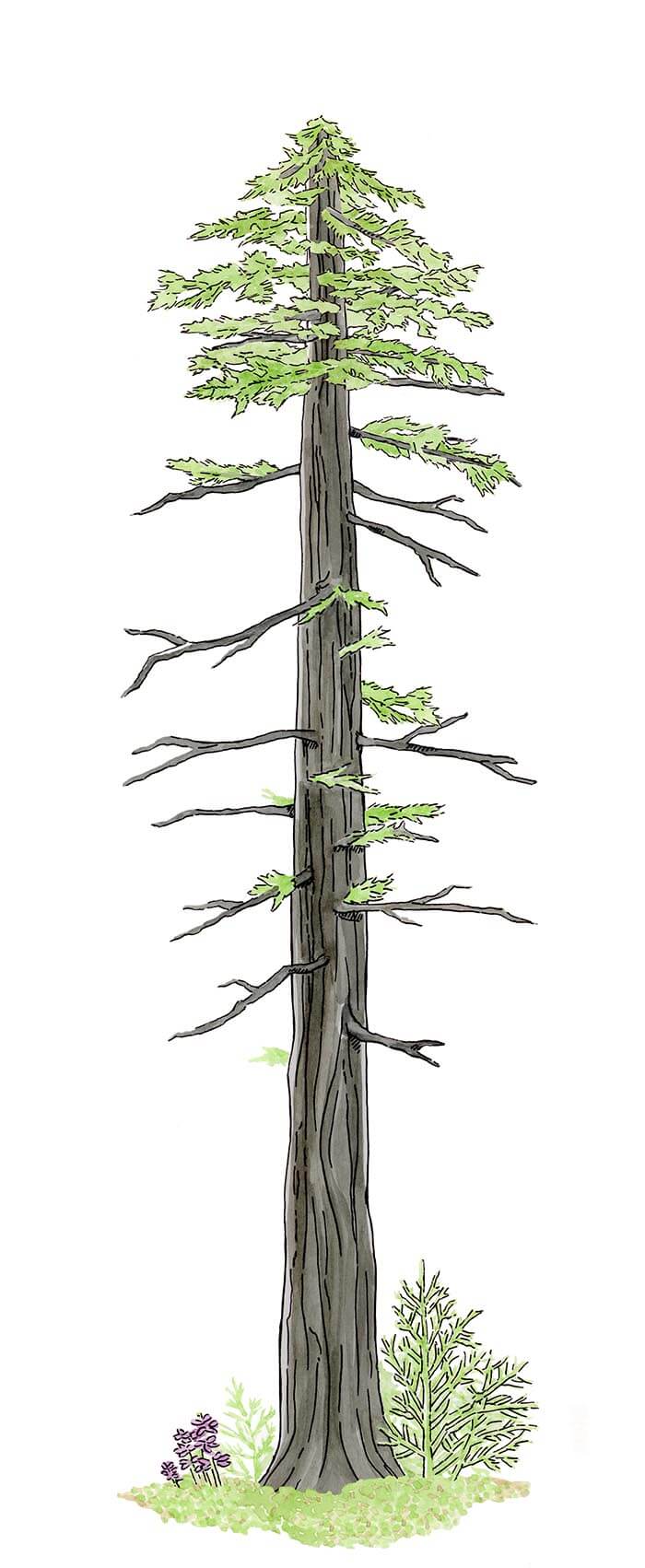

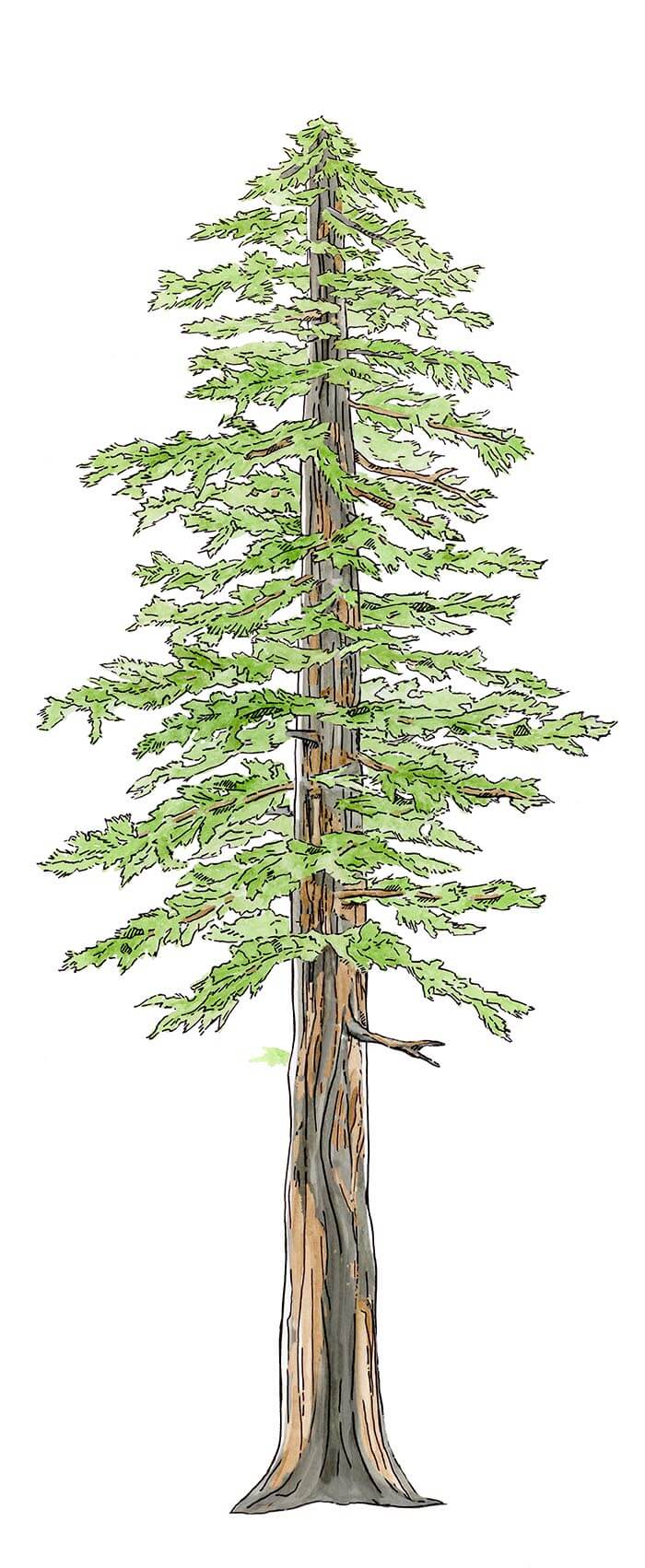

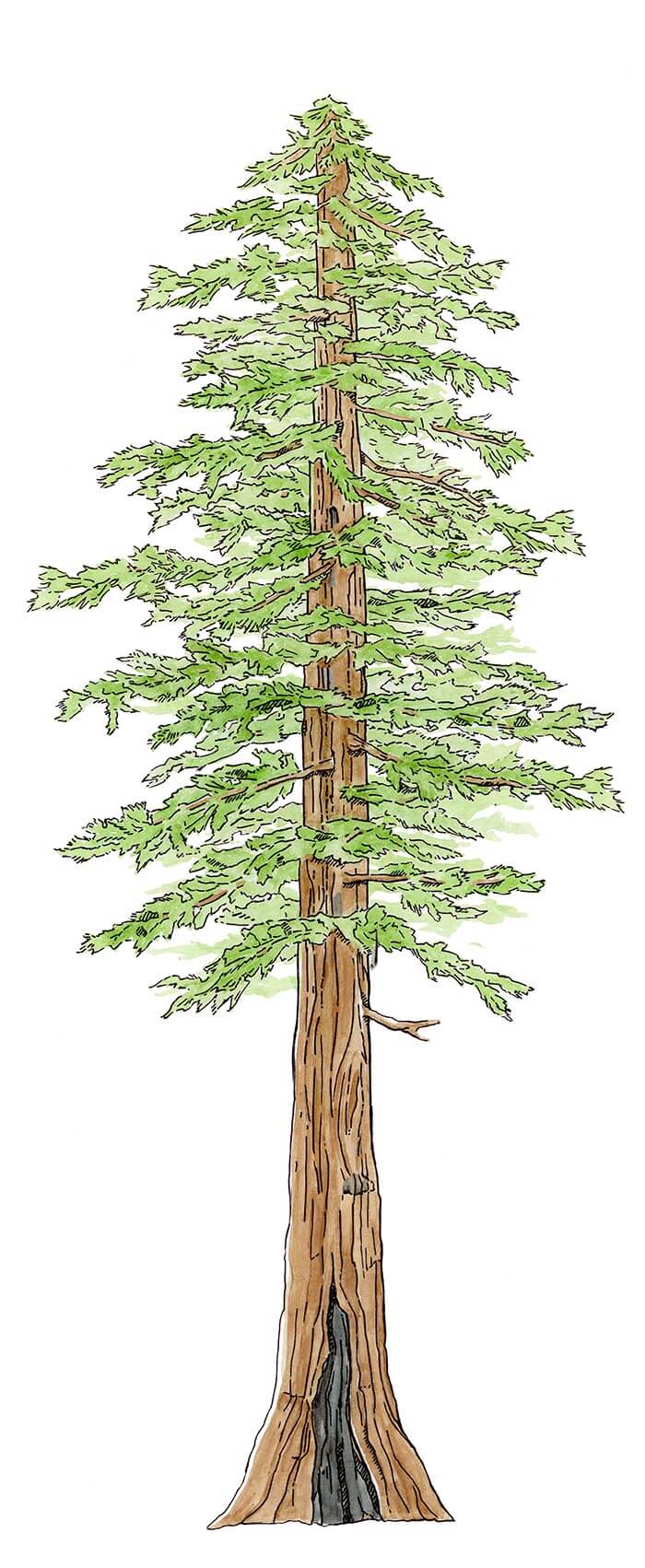

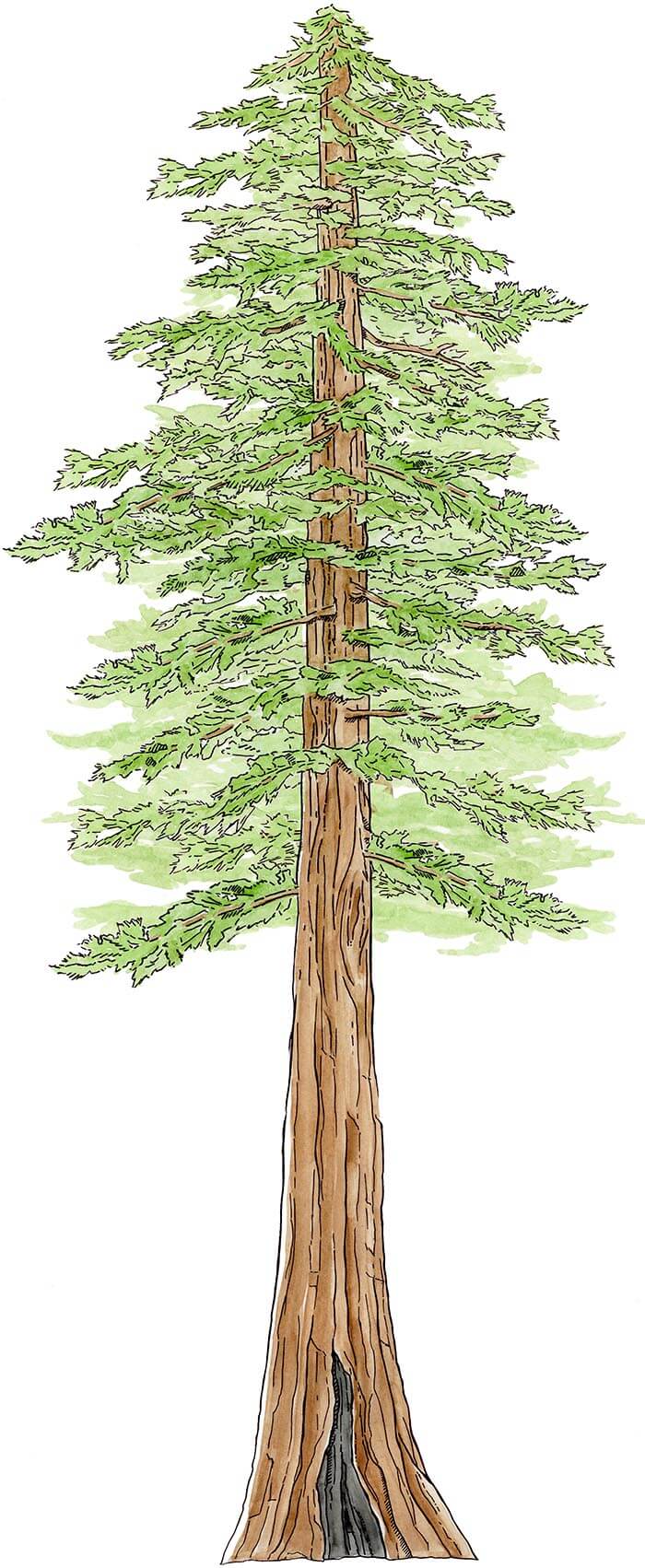

And unlike most other West Coast conifers, a redwood can survive even if most of its canopy burns off. Following a fire, a surviving redwood will shoot out a fuzz of electric green sprouts along much of its blackened trunk, aiming to “quickly rebuild its crown and regain photosynthetic surface area that was lost,” Moore said.

In the days and weeks following the CZU fires, Sempervirens Fund asked people to share their memories of Big Basin State Park on social media. “That ask was geared to what we thought was our community: our neighbors, people who’d had to evacuate their homes, people who live, work, and play in the Santa Cruz Mountains,” says Matt Shaffer, communications director at Sempervirens Fund. But within days, the post had millions of views, and memories streamed in from people all over the world. Shaffer says the global outpouring that followed news of the park’s fate is just one signal of Big Basin’s enduring importance.

And it gives you an inkling of the flavor and number of questions that Kerbavaz and her colleagues have been fielding for months. “Now everyone wants to know: how long will it take until Big Basin looks like it used to look?” she says. “Those are questions we just don’t have a good guideline on.”

For one thing, last August’s fire—while it wasn’t a knockout punch—was the biggest and hottest to burn through old growth redwoods since scientists have been keeping track. Across their present range and throughout much of their recent adaptation, redwood forests are estimated to have burned on average every 6 to 25 years. But in the era of fire suppression the so-called fire return interval in redwood forests has grown. So Kerbavaz and her fellow scientists don’t have much in the way of analogs to feed into their recovery models. Instead, they’re extrapolating from findings in timber industry research, from intense fires in other ecosystems, and from studies of smaller burns like the 2003 Canoe Creek fire in Humboldt Redwoods State Park, and fires in second-growth stands, like the lightning-caused fires in Big Sur and the Santa Cruz Mountains in 2008. Meanwhile, nobody can be sure how the ongoing drought and our ever-warmer climate are affecting how the forest is already recovering, let alone its long-term prospects. “A lot of these are changes that may impact the timelines for recovery,” Kerbavaz says.

Also, how soon the forest will recover depends on what part of the forest you’re asking about. Across all 18,000 acres of Big Basin, variations in local moisture, slope, aspect, fire history, and forest composition affected the fire’s behavior. “The effects are patchy. Not everywhere in Big Basin burned equally,” Moore says. You can see it in aerial imagery captured in the months following the fire: the few acres surrounding park headquarters are a mosaic of green, brown, and black. In the greener areas, “most redwoods did okay,” says Moore. But in the blackened areas, “that’s where the fire burned extra hot, and I’d imagine 40 to 50 percent of the redwoods in those patches will not come back.” By observing conditions on the ground and comparing aerial imagery from before and after the fire, Moore estimates that 10 to 20 percent of the park burned severely. And recent observations of green growth in the worst-hit areas mean root systems may have survived, which is critical, especially during extreme drought.

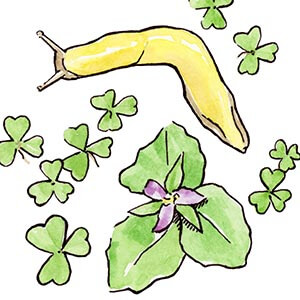

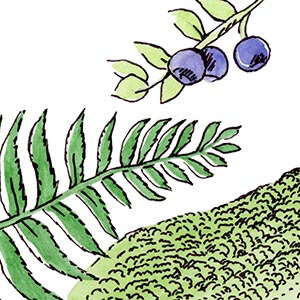

Redwoods might be Big Basin’s “charismatic megaflora,” as Kerbavaz says, but they’re just one species in the diverse ecosystem of the Santa Cruz Mountains. In a landscape with an estimated fire return interval of 10 to 12 years, each species has developed its own traits and timeline to survive or regenerate. And it comes as a cosmic relief to hear that in the year since the CZU fire, researchers have already observed those cycles playing out at Big Basin. “Pretty much everything seems to be coming back in the way we’d expect, given what we know from the literature,” Kerbavaz says. “Every species for which the strategy is to grow from seeds appears to be growing from seeds. Everything that is engineered to resprout appears to be resprouting. So I don’t think we’re seeing the loss of any species following the CZU.”

If Big Basin’s recovery roughly follows the trajectory scientists have observed following other redwood burns, in the years to come, “The forest will recover from the ground up,” Moore says. In two to five years, he estimates the fire’s remnants on the forest floor will be all but gone. Sparse as this winter’s rains were, they were enough to coax a vibrant bloom of wildflowers and sorrel by spring. Kerbavaz, meanwhile, spotted banana slugs and salamanders in June, and told me about the educational native plant garden in front of headquarters: “That garden came roaring back this spring,” she said. “Even though the building next door burned with sufficient intensity to melt glass and crack the stones in the chimney, every plant came back next to its little label.”

Redwood Fire Recovery Timeline

Credit: Shirley Chambers

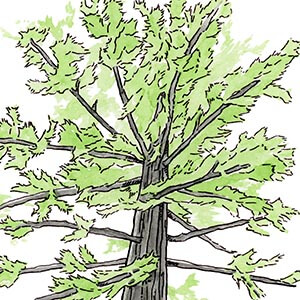

Especially in the hotter areas of the burn, the trees that make up the lower part of the canopy—oaks, tanoaks, and madrones—burned, and even if they’re still standing, they’re likely dead. But these species survive belowground, and Kerbavaz has seen fresh their shoots already reach six feet, though it will likely be another 30 or 40 years before these shoots grow into full-sized trees.

Meanwhile, high overhead in the upper canopy, the fire’s aftermath will linger longer. Last August’s fire torched the canopies off of an estimated 20 to 30 percent of the mature redwoods, leaving some trees basically limbless, but alive. Moore says those surviving trees’ first priority for the next 7 to 10 years will be to regrow their canopies—an acre or more of leaf surface area to a single tree. Initially, crowns regrow quickly enough that within a decade, Moore guesses people hiking through much of the park should find it “pretty shady and nice” on the forest floor. But many surviving redwoods lost branches that were themselves the size of good-sized trees. So it will be another century or two until some trees regrow their massive, complex canopies. Losing so many big branches is bad news for marbled murrelets, the endangered sea birds that nest only in the biggest limbs of old growth West Coast forests. But the fire could be a boon for California condors, at least one of which has already nested in Big Sur since last year, in a high-up cavity of a fire-scarred redwood from the 2008 fire. And there’s this glimmer of hope: a marbled murrelet was observed nesting in Big Basin already this year.

Meanwhile, the fire killed most of the park’s knobcone pines and Douglas firs, which lack the redwood’s physical defenses, and don’t resprout once the main trunk dies. Before the fire, giant Douglas firs—some of them up to 270 feet tall, and the oldest 300 years old—made up 30 percent of the forest canopy.

“Those will sprout from seed, and they will simply take time to come back,” says Kerbavaz. “If you assume some of those big Douglas firs were on the order of 200 to 300 years old, that’s how long it’ll take to regrow trees of the same size.”

Caveats, complexities, and climate change notwithstanding, the answer to the question of “How long will it be until Big Basin looks the way I remember” depends almost as much on who’s asking, and what they remember about the park before it burned.

But if your impressions of the place are more gestalt than specific, then you might get some comfort from an account of a fire that swept through Big Basin in 1904. The book California Redwoods Park: an Appreciation was written by one of the park’s boosters in 1912, part of a campaign to fund improved road access and visitor amenities. A chapter on the 1904 fire describes some depressingly familiar scenery: “For weeks the midday sun was a ball of fire in a bank of smoke … A trackless, trailless area of ashes … Fires were burning at the base of hundreds of magnificent redwoods and flames darted from the tops of tall firs.”

But just a few paragraphs later, the flames are out, and winter rains are in. “Vegetation sprang from the Earth with more than Phoenix-like vitality, and within a year the landscape was reverdured … Now, after eight years, the visitor finds little in the general aspect to suggest a conflagration … Perhaps but for this catastrophe we would never have known how ever-virile this forest was.”

Read more about what's happened over the year since the fires. You can also join California State Parks with Reimagining Big Basin.