Beyond the Bloom: Superblooms in the Santa Cruz Mountains

All photos by Orenda Randuch

Superbloom

“Superbloom” may conjure images of fields bursting with bright orange poppies, purple lupine, and yellow mustard flowers that can be seen from space, but for nature, this fleeting beauty means so much more. For many native plants adapted to California’s conditions, a superbloom is the culmination of natural phenomena aligning at just the right time to support the next generation. Phenomena like fire to release dormant seeds and plentiful rains in winter followed by warmer, longer days signaling it's safe to expose precious pollen. But those conditions aren’t uniform across the state.

Here in the Santa Cruz Mountains, diverse habitats formed by elevation, geology, sun exposure, and water, just to name a few, create microclimates–pockets where conditions can be markedly different than those nearby. So as superblooms in warmer areas are ending, others are just getting started. “Our region was delayed due to the frost and rain we had into early spring. Seeds in the soil need warm temperatures in order to know conditions are good to sprout,” Beatrix explains.

Microclimate

Protected in San Vicente Redwoods lies a mixed ecosystem of meadows, forests, ponds, and streams fed by a high water table creating springs, seeps, and wet meadows. Shaded by the recovering redwood forest and cooled by plentiful waters, the superbloom here is delayed despite the warm day above the blanket of coastal fog. The superbloom’s usual suspects of poppies and lupine are just beginning to color the fields. The 2020 CZU Fire returned nutrients to the soil, opened up space and sunlight, and awakened fire-following seeds lying dormant in the earth. Blooms are expected here, but the superbloom has not fully blossomed just yet.

The superbloom’s usual suspects of poppies and lupine are just beginning to color the fields. The 2020 CZU Fire returned nutrients to the soil, opened up space and sunlight, and awakened fire-following seeds lying dormant in the earth. Blooms are expected here, but the superbloom has not fully blossomed just yet.

“With the changing climate, we’ve been experiencing extreme weather events which can impact the conditions the plants had evolved to adapt to,” Beatrix says.

“Wildflowers are essentially a wild plant with flowers. The flower is the reproductive part of the plant and will produce a seed,” she points out. And every step of the way the plant is supporting other species around it with its leaves, flowers, and seeds. She hikes carefully through the meadow, skirting ponds and seeps in search of some of the wildflowers often overlooked during a superbloom that should not be underestimated.

Beyond Basic Blossoms

“I’m fascinated by large, lush, deciduous shrubs,” Beatrix says. “So much effort in one year.”

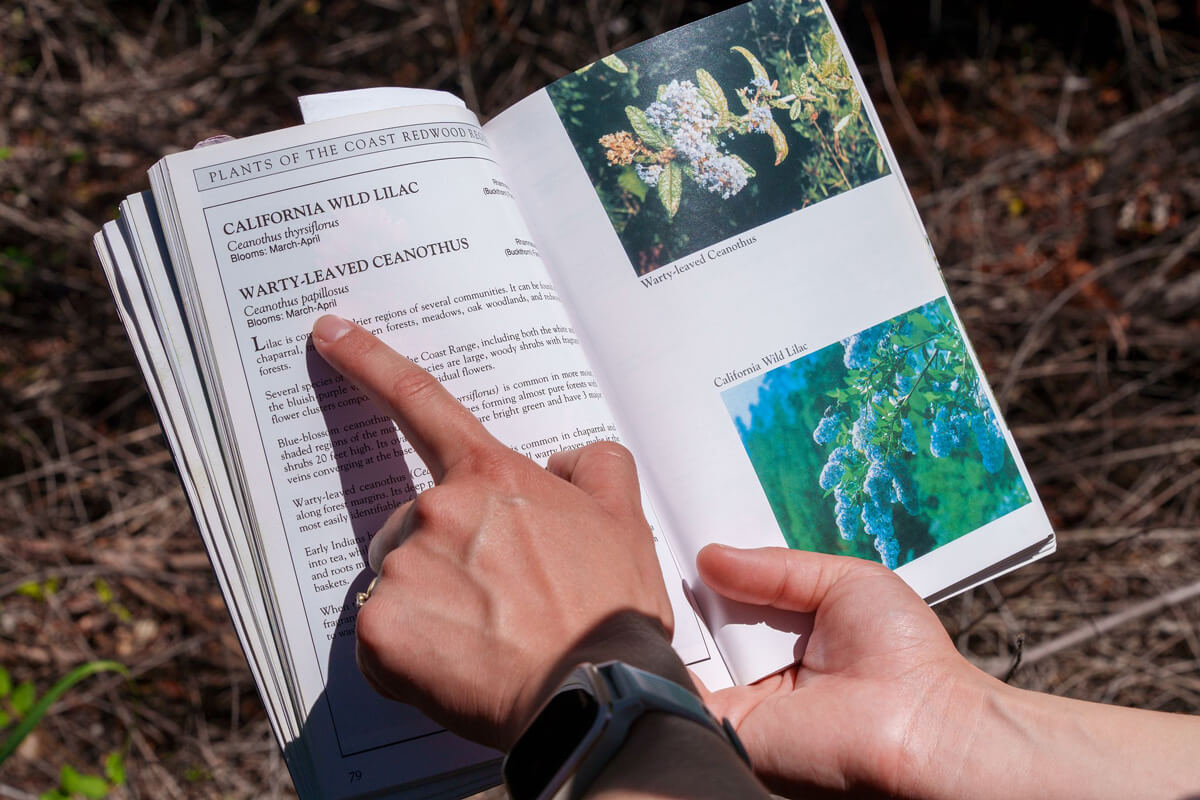

Pushing toward the upper limits of their height range, towering fire-adapted ceanothus are thriving after the CZU Fire, which means the plants and the wildlife these three different varieties support can thrive too. Their lovely fragrance scents the air, attracting hundreds of insects including bees and butterflies and below ground they are fixing nitrogen in the soil which benefits the plant community long after the fire.

Hiding along the meadow’s forested edges, the generous western thimbleberry's large leaves offer shade and shelter while its big white blossoms await pollination to provide food in return. “Western thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus), have large leaflets which can provide shade and cooling for the soil and water on the forest floor,” Beatrix illustrates, "and they produce edible berries many creatures can forage,” she continues, “they provide food, shelter, and habitat for resident species”.

California phacelia (Phacelia californica) can grow in many plant communities but its seeds are photodormant: they can only germinate in darkness. “Pollinators love it!” Beatrix says. “I once walked through a field of them in the understory of a post-fire evergreen forest, and there were sooo many bees–you heard the ‘buzz’. Its long-lasting blooms attract many bumble bees, beetles, and hover flies which help to naturally control aphids and other plant pests.”

“Broad leaf lupine (Lupinus latifolius) is a member of the pea family so each fertilized flower becomes a fuzzy little pod of seeds which provide food to creatures as well as help to begin the next generation of these nitrogen-fixers which help restore habitats by returning nitrogen to the soil and benefits all surrounding plants,” Beatrix notes.

Fernald’s iris (Iris Fernaldii) is endemic to western parts of Northern California where its typical blooming period is considered to be April. Douglas iris (Iris douglasiana) typically blooms later in the year from about May to July. In a nearby region, the irises are thought to have hybridized. “These irises are a great example of the biodiversity here as well as the role microclimate conditions can play making bloom periods less predictable, “ Beatrix points out. “Not only are we seeing both iris types here but both are blooming at the same time.”

Neither red nor violet, bright yellow redwood violets (Viola sempervirens) can be seen popping up amongst the redwood sorrel's pale lavender flowers and clover-like leaves that carpet the redwood forest understory as early as January and usually last through May where they host many butterflies.

While identifying some species can be incredibly nuanced, Beatrix points to the two purple dots on either side of the white flower for which two-eyed violets (Viola ocellata) get their name, “other local violets don’t have those,” she says.

At first glance the small withered flowers, few and far between, may seem the antithesis of a superbloom but it's perhaps the most exciting botanical sight of the visit. Beatrix closely examines the leaves and points to where they emerge almost directly out of the branch, “There’s little to no petiole, “ she says, “they’re Santa Cruz manzanita!” she exclaims. The incredibly rare and endangered Santa Cruz manzanita (Arctostaphylos andersonii) is known to exist on this remote area of San Vicente Redwoods but its a seeder rather than a resprouter like other manzanitas, so fire kills it. Beatrix checks the leaves of nearby manzanitas for stems, their flowers giving way to edible berries, and several pass the leaf test confirming we’re standing amidst a growing population of rare natives whose berries and flowers support dozens of birds, bees, butterflies, and moths.

"Every rose has its...prickle. Sorry, Poison," Beatrix laughs. Although both defend a plant from being eaten, prickles—as seen on this wood rose (Rosa gymnocarpa)—are modified epidermis and softer than thorns which are modified shoots like stems or branches.

This globe lily (Calochortus albus) has many common names but Beatrix prefers fairy lantern, “I love the little dainty fairy lanterns. I like to imagine them glowing at night.”

Pacific starflower (Lysimachia latifolia) can bloom through July and grows in shaded wet areas like creeksides, moss, and mossy rock faces. “They like soil rich with organic matter, so its presence can be an indicator of the nutrients replenished by the fire,” Beatrix says.

Blue-eyed grass (Sisyrinchium bellum) isn’t truly a grass but its blooms can be seen amongst grasslands and woodlands as late as July where there is some moisture and then these drought-adapted natives die back to the ground and lie dormant for the rest of the summer.

Yerba santa (Eriodictyon californicum) has been thriving in many parts of the CZU fire’s footprint. “This fire follower can grow quickly after a fire taking advantage of the new space and sunlight but it will get shaded out by taller plants as they recover and catch up,” Beatrix explains.

Although people don’t generally appreciate its fragrance, its flowers attract many insects like butterflies, moths, and especially bees.

Even native grasses like California oat grass (Danthonia californica) bloom this time of year and can support more insects than non-native grasses. “Native grasses are food for insects, which are food for insectivorous bats and birds, small mammals and reptiles, which support raptors and other mammals that use grasslands as their hunting grounds,” Beatrix points out.

Common cow parsnip (Heracleum maximum) can be confused with the dreaded invasive poison hemlock. “I love seeing this native deciduous perennial because when I first see it I’m like ‘ugh, poison hemlock… wait, never mind it’s cow parsnip!’ They both grow tall and have big white umbel inflorescences, except hemlock is a very invasive non-native plant,” Beatrix shares.

Crevice alumroot (Heuchera micrantha) can bloom pink, white, or greenish through the summer. Regardless of the color, native bees and hummingbirds love the flower’s nectar. “Look for them on moist, rocky banks and cliffs,” Beatrix suggests.

Tiny ivory buds will soon beckon pollinators to a plant that most humans prefer to stay away from—poison oak. “Poison oak is so cool because it has a variety of growth forms depending on its habitat and can blend in with oak leaves, so you’ll notice different leaf margins between plants. Hence its name Toxicodendron diversilobum,” Beatrix points out which roughly translates to “diverse lobes” referencing its ability to diversify its leaves to mimic an oak. But those same leaves that induce rashes in humans offer a great source of phosphorus, calcium, and sulfur to wildlife like deer and squirrels above, and shelter to birds who eat its berries and germinating seeds and growing seedlings especially in areas recovering from fire. So, we tip our hats to this native wildflower–from a distance.

Species Survival

The very conditions that may be delaying the expected superbloom here are exactly what can offer refuge to species of plants and wildlife alike. With year-round water, shaded forests, and a plethora of native plants a great number of species are supported in this microclimate. And as temperatures continue to rise, pockets like this can remain cooler and wetter than surrounding areas so redwoods and the myriad of native species like these they support can continue to survive here.

Biodiversity

“It makes me so happy to see a post-fire landscape with high ecological diversity. Being here and seeing the birds, plants, insects, ponds, and the community coming to life is so mesmerizing. It’s life functioning as part of an ecosystem.”

Carbon Sequestration

Redwoods are known for their unparalleled ability to pull carbon dioxide from the air and store it in their vast, long-living and decay resistant wood but these meadows are also storing carbon beneath the earth. “Native plants have adapted to this habitat and co-evolved with other species here. Their root systems are often deeper to survive droughts and more robust to link with the plant community through fungal partners than their non-native competition. Each of these native wildflowers is storing carbon underground in its root systems and helping to fight climate change,” Beatrix explains.

Fire, Flowers, and the Future

This portion of San Vicente Redwoods is just a dozen or so acres of the more than 12,000 acres of protected lands where we are chronicling the natural resources to help them be resilient for the changes ahead. “We hope to bring prescribed fire to these grasslands, and work on tackling the invasive plants,” Beatrix says of stewardship plans to care for this microrefugia and the biodiversity it supports so there will be flowers far into the future.

You can help to support work like this by making a gift to Grow the Forest.

Snake in the Grass: non-native rattlesnake grass heavy with seeds and native wildflowers behind. Prescribed fire can help reduce non-native plants while enriching the soil and stimulating native fire-adapted plants.

All photos by Orenda Randuch.

More to Explore

- Learn more about Wildflowers After Wildfire

- Read more about what it takes to restore native plants

- Read more about San Vicente Redwoods