Lichens

photo by Orenda Randuch

Lichens of the Redwoods

by Rikke Reese Næsborg, Ph.D., Santa Barbara Botanic Garden

Lichens are curious. Each is actually not a single organism, but rather a little ecosystem consisting of various fungi, algae, and bacteria living together in symbiosis.

Lichen Facts

- Lichens are ecosystems of various fungi, algae, and bacteria

- Lichens can break rocks into soil

- Lichens keep the forest cooler and wetter

- Lichens take 4 billion tons of CO2 (emissions from 860 million cars) out of the air each year

- Lichens are more abundant in southern redwoods like the Santa Cruz Mountains

But when hiking through a redwood forest, it’s probably the towering trees, not the lichens, that you first notice. An observant individual might see a pale bluish-green dust on a tree’s lower trunk, or maybe a myriad of miniscule scales commingling with red-capped stalks. Known as dust lichen (Lepraria sp.) and pixie cup lichen (Cladonia sp.), respectively, these two common lichens often colonize the damp bases of large, old redwood trees.

Bluish-green powder of a dust lichen (Lepraria sp.) growing on redwood trunk. Photo credit: Allison Green Kidder.

Red-capped stalks of lipstick cup lichen (Cladonia macilenta) are peeking up among the tiny scales at their base. The red caps are fruiting bodies where the fungal spores are produced. Lipstick cup lichen is one of several pixie cup lichens commonly found in redwood forests. Photo credit: Rikke Reese Næsborg.

However, not many lichens can tolerate the low-light conditions of the forest understory. In fact, the vast majority of lichen biodiversity in a redwood forest is hidden high above the ground.

Levels of Lichen

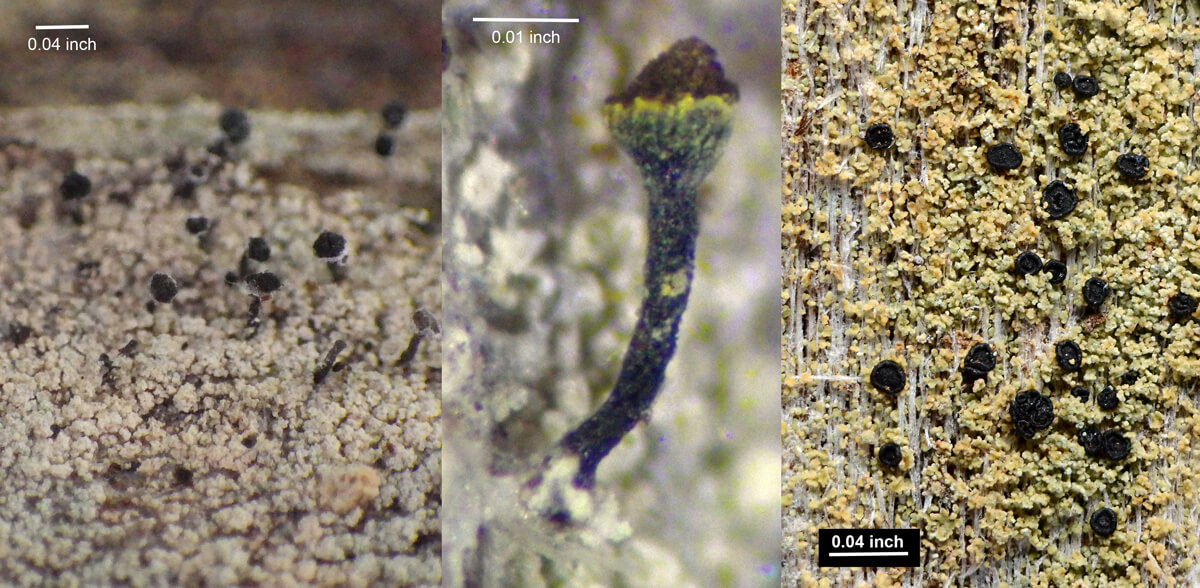

On the massive trunk, miniature pin lichens (Calicium sp. and Chaenotheca sp.) and the tiny scales of a clam lichen (Carbonicola sp.), including species nobody has seen before (Williams & Tibell 2008, Reese Næsborg et al. 2019, Bendiksby et al. 2018), occupy furrows in the fibrous bark.

Three species that were new to science were discovered during climbs in just 24 redwood trees. From left to right: redwood stubble (Calicium sequoiae), long-spored stubble (Chaenotheca longispora), and canopy froth (Xylopsora canopeorum). All three were found on the thick, fibrous bark of large trunks between 16 and 263 ft above ground. Photo credits: left and middle, Rikke Reese Næsborg; right: Einar Timdal.

You need a hand lens or a magnifying glass to spot these tiny stubble lichens (Calicium sp.) that can cover large areas of the trunk despite their miniature size. Photo credit: Rikke Reese Næsborg.

This clam lichen (Carbonicola anthracophila) has an affinity for burnt bark and wood, but will also occupy the unburnt, fibrous bark of large trunks. Photo credit: Einar Timdal.

The flaky bark of small, sinuous redwood branches is adorned by saucer lichen (Ochrolechia sp.) showing off its tiny, pale orange discs over a white background.

Saucer lichens (Ochrolechia sp.) are common on redwood bark. Although they are usually decorated with abundant little pale-orange fruiting bodies, sometimes a paint-like splash of white is the only evidence that a lichen is growing there. Photo credit: Rikke Reese Næsborg.

Yellow-green, leaf-like, greenshield lichens (Flavoparmelia caperata) cover the entire upper surface of a branch.

Greenshield lichen (Flavoparmelia caperata) and its look-alike speckled greenshield lichen (Flavopunctelia flaventior, insert) can be tricky to tell apart, but look for tiny white dots speckling the surface of the speckled greenshield lichen. Photo credit: Rikke Reese Næsborg, inset: Stephen Sharnoff (CC0 1.0 (Public-domain)

Splintered wood chunks left behind from sheared off branches may hold a completely different community of lichen species.

Dead pencil-thick twigs can be so covered in lichens that the twig is barely visible.

One little redwood twig can host entire lichen communities—this one is home to at least six different species. Photo credit: Rikke Reese Næsborg.

As the elevator finally reaches the tree top, you might see pale yellow-green witch’s hair lichens (Alectoria sp.), beard lichens (Usnea sp.), and brown horsehair lichens (Bryoria sp.) tangled like tinsel in the outermost branches and leaves. Tube lichens (Hypogymnia sp.) are also abundant in the upper crown.

Witch’s hair lichen (Alectoria sp.) drapes over branches. This kind of pendant lichen will often fragment, disperse in the wind, and then continue growing if landing on different branch in a suitable location. Photo credit: Rikke Reese Næsborg.

Looking up toward the very top if the tree, lots of beard lichens (Usnea sp.) and tube lichens (Hypogymnia sp.) are visible. These species can tolerate, and perhaps even prefer, high exposure to sunlight, wind, and repeated cycles of wetting and drying. Photo credit: Rikke Reese Næsborg.

Horse-hair lichens (Bryoria sp.), here seen in the lower crown, are among species that in the southern part of the redwood range are mainly found in the upper and middle crowns of the trees. Like witch’s hair lichens and beard lichens, horse-hair lichens also fragment and can continue growing if they land in a suitable location. Photo credit: Troy McMullin (CC BY-SA 3.0).

High and Dry

Why do the lichen communities change with height? That’s because different parts of the tree offer different microhabitats, and many lichens are quite picky about their living conditions. At the base of the tree, conditions are typically evenly humid, dark, and cool, and the bark of the tree is thick and fibrous. Some species, such as dust lichens and pixie cup lichens in addition to many types of mosses, prefer these conditions. Moving up the tree it gets increasingly drier, brighter, and warmer, and the bark gets thinner and flakier. Finally, the tree top is more frequently wetted by gentle rain and dew, but it also dries out fast due to wind and sun exposure. Some species, such as witch’s hair, beard lichens, and horsehair lichens, prefer these tree top conditions and can therefore reach their highest abundance there.

Hidden Redwood Ecosystems

At first glance, redwood trees may appear to be a poor host to lichens, especially compared to neighboring conifers such as Douglas-fir and western hemlock that typically support much higher biomass of lichens. However, the number of lichen species found on redwood can be far greater than on these other conifers. For example, a single redwood tree in Big Basin Redwoods State Park was host to more than 100 species of lichens and mosses, and over 300 species were documented in just 24 trees across six different redwood state parks. This incredible diversity is likely a result of the many different types of microhabitats that occur in old redwood trees.

“a single redwood tree in Big Basin Redwoods State Park was host to more than 100 species of lichens and mosses”

And since some redwoods endure millennia of punishing winter storms and ferocious crown fires capable of shearing large branches and snapping enormous trunks, the resulting damage offers a myriad of microhabitats to lichen communities, including charcoal, splintered wood, rot pockets, and even deep accumulations of canopy humus perched in cavities. Some lichen species favor burnt wood, while others prefer hard, unburnt wood. In the northern part of the redwood range, decaying pockets of wood are commonly occupied by shrubs such as evergreen huckleberry or even trees such as western hemlock. Compared to redwood, the bark of these epiphytic shrubs and trees has different chemical and textural properties, so they sometimes harbor very different lichens, further amplifying the total number of lichen species found in redwood forest canopies.

If you’re interested in learning more about lichens, start by noticing the shapes and colors of lichens and what they grow on. And if you visit a redwood forest soon after a storm, you won’t need the glass elevator to see more of what the canopy hides—a fallen branch or trunk offers an easy glimpse into the communities that grow high in a redwood forest canopy. Happy lichenizing!

Are you lichen learning about the hidden biodiversity redwoods hold high above the ground? Get a sneak peek of Dr. Næsborg’s not yet published lichen research in her Under the Redwoods webinar recast. Join her to explore the tiny critters on giant trees in the northern and southern ends of the redwood range, how they’re different, and what it could mean for redwoods in our changing climate.

More to Explore

- Learn more about Tiny Critters on Giant Trees with Dr. Rikke Reese Næsborg Under the Redwoods

- Read more about fungi’s other symbiotic partnerships in Underground Allies by Dr. Kaishian

- Meet the Mushrooms of San Vicente Redwoods in our funguide Fungi of the Forest