Chronodiversity in Redwood Forests

Chronodiversity in Redwood Forests

Among the hallmarks of healthy redwood forests are trees of varying ages growing and thriving together. Achieving this diversity of ages, or chronodiversity, can improve old-growth conditions, which leads to greater habitat diversity—two essential outcomes for redwoods to thrive in the Santa Cruz Mountains.

Read on to learn about the importance of chronodiveristy in coast redwood forests.

Stronger Together

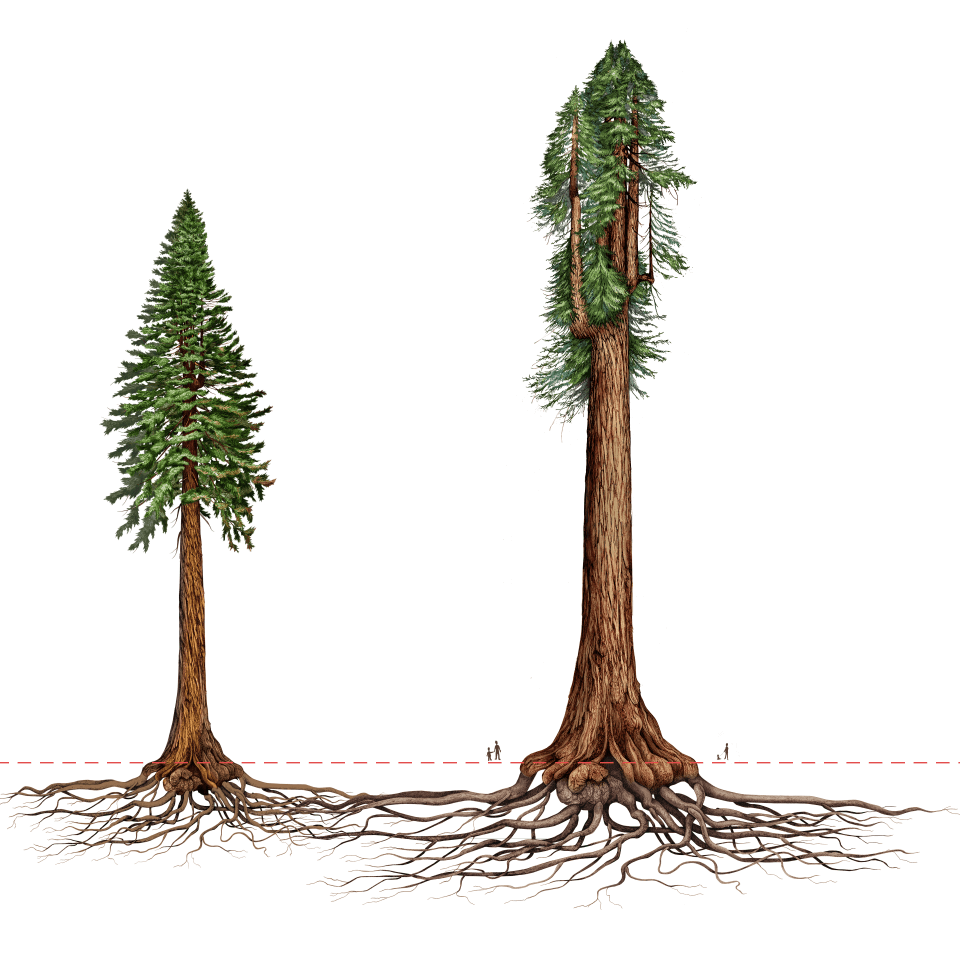

Redwood forests are so much more than a collection of towering trees. We have learned that redwoods are stronger together, forming an interconnected system unique among evergreens that nurtures young trees, supports older ones, and creates conditions for the whole forest to thrive. A key factor in the community resilience of the redwood forest is the concept of chronodiversity, or the condition of temporal richness in a particular habitat or ecosystem, and, within communities of plants, specimens of various ages. In his book, Elderflora: A Modern History of Ancient Trees, historian Jared Farmer explores the complex history of the world’s oldest trees. In a changing climate, a long future for these big trees is still possible, Farmer shows, but only if we give care to young things that might grow old.

Illustration courtesy of Jane Kim, Ink Dwell Studio

A redwood forest masterfully provides care to young things so that they might grow old. The redwood’s shallow but widespread roots help them survive by intertwining with the roots of other trees around them. Intertwined root systems provide stability to these mighty trees during strong winds and floods - quite literally holding one another down. Their shallow roots can also sprout and support new redwood trees far more successfully than from their cone seeds.

Redwoods can often be seen growing in circles, known as “fairy rings” or “family circles”, because they sprouted from the roots or base of a parent tree. The parent tree helps to nourish the sprouts through its well-established root system while they grow. When the parent trees die, the young redwoods continue to grow in the circle shielding, stabilizing, and nourishing each other through their roots. Redwoods, even unrelated ones, take care of one another, supporting each other with nutrients through their interconnected roots including their young, sick, and old. This chronodiversity is foundational to the sustainability of healthy redwood forests.

The Importance of Old-growth

Photo by Orenda Randuch

Old-growth redwoods are the essential anchors of a chronodiverse redwood forest. Even more broadly, Farmer names old-growth redwoods as lynchpins of our planet’s chronodiversity as a whole. Old-growth redwoods are both megaflora, the largest plants of a particular region, habitat, or epoch; and elderflora, the longest-lasting plants of a particular region, habitat, or epoch.

Extreme climate conditions and weather events are not making this any easier. Stresses from heat, drought, and wildfire are increasingly putting redwoods, and the chronodiversity necessary for their long-term survival, at risk. Sustaining healthy and chronodiverse redwoods also addresses climate change: no other species stores as much carbon as a redwood tree.

Protecting and connecting remaining old-growth redwoods and second growth trees that will grow into old-growth ensures these interconnected natural systems can continue to function, so the healthy forest can sustain itself – and us. Not only do chronodiverse groves help one another thrive, combined they also provide exponentially greater habitat for plant and wildlife species. Although only 5% of old-growth redwoods are left in their native habitat, by preserving the land they grow on and restoring natural conditions, we’re helping to create the old-growth forests of tomorrow.

Restoration Fosters Chronodiversity

Photo by Orenda Randuch

Creating the conditions for thriving, chronodiverse redwood forests is a challenging work in progress. After decades of heavy logging, newer trees often regrow all at once, too close together and forced to compete for space, sunlight, and water. The lack of resources for all the trees can leave them stunted and unable to reach their full potential, and more importantly, can crowd out larger, more essential older trees.

At places like San Vicente Redwoods, foresters are selectively cutting smaller trees and thinning the understory, aiming to help the biggest trees in previously logged stands grow faster. Thanks in part to research from scientists like dendrochronologist Allyson Carroll, “we know bigger, older redwoods are more resilient to disturbance from catastrophic wildfire, storms, floods, disease, you name it,” says Laura McLendon, director of land conservation for Sempervirens Fund. “So, the quicker you can return second-growth forests to certain old-growth characteristics like wider spacing, the better.” The goal is eliminating some of the ecological hurdles left by over a century’s worth of logging, road building, fire suppression, and development. By helping to restore ideal conditions through careful stewardship, chronodiverse redwood forests, anchored by old-growth trees, can again thrive.

A redwood forest is resilient. By protecting and connecting redwood forests in the Santa Cruz Mountains, we help redwoods grow stronger, together. Once it’s protected, restored, and chronodiverse, a redwood forest can take care of itself. We’re encouraged that redwoods sprouted at the time of our founding 125 years ago are only a few short years from becoming venerable old-growth themselves, providing plant and wildlife habitat, clean air, and inspiration for thousands, even millions, of years to come.

More to Explore

- Learn more about how we're Growing Old-Growth today for tomorrow.

- Read our Climate Action Plan to help redwoods survive so we all can thrive.

- Explore our collaboration with Bay Nature magazine: "Why Cut Redwoods?"