photo by Pathways for Wildlife

Here are some of the most iconic and fascinating animals we support when we protect redwoods.

Banana slugs (Ariolimax spp.) are native to the redwood forests of the Pacific coast in North America, and you can often see them out and about when the forest is wet. Visit redwood forest parks in the Santa Cruz mountains, and you can see banana slugs making their way through the forest floor where they are busily – albeit slowly – returning nutrients to the soil and spreading seeds and spores. Just remember to watch your step on the trail! Not all banana slugs are the iconic and eye-catching bright yellow. Learn more about banana slugs.

photo by Ian Bornarth

Bobcats

Bobcats (Lynx rufus) are adaptable to many different types of habitats but, preferring woodlands, they are well-suited to the Santa Cruz mountains, where they can be found–if they want to be. Their spotted coats, for which they were once hunted to near extinction, provide excellent camouflage for their own hunting–helping to keep small mammal and insect populations under control. Unfortunately, in the Santa Cruz mountains habitat fragmentation from development and poisoning from rodenticides (intended to control the very pests bobcats prey on) have become the biggest threats to their survival. In addition to protecting natural habitats where bobcats can thrive, using alternative pest control methods – like installing owl boxes to help naturally control pests – can greatly help bobcats continue to roam the region’s forests.

photo by Ian Bornarth

California Newts

True to their name California newts (Taricha torosa torosa) are endemic to California, living near water sources where they breed, such as the wet redwood forests of the Santa Cruz mountains. These spellbinding little beasts are also surprisingly deadly. The glands in their slimy skin secrete the potent neurotoxin tetrodotoxin, which is also found in pufferfish and harlequin frogs. Hundreds of times more toxic than cyanide, it’s strong enough to kill most vertebrates, including humans – but only if ingested. So, as a general rule, try to restrain from eating one. Or touching one if you have any open wounds. A California newt may curiously help remind you by taking a defensive posture lifting up their heads to reveal their bellies which are brightly colored – a common poison warning in nature.

photo by Connor Long

California Red-legged Frogs

So called for its red lower abdomen and underside of its hind legs, the California red-legged frog (Rana draytonii) is the largest native frog in the western United States. Sadly, California’s official amphibian is also a federally listed threatened species due to habitat loss and invasive species like the non-native American bullfrog. Their habitat must stay moist and cool through the summer, including slow-moving streams, ponds, and upland shelters such as rocks, small mammal burrows, logs, dense vegetation, and even man-made structures, such as culverts. California red-legged frogs help to keep insect populations in check and are an important food source in the ecosystem for other predators such as the endangered San Francisco garter snake in San Mateo County.

photo by Greg Schechter

You may be thinking, salmon in the forest? Critically endangered coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) are anadromous fish, which means they live part of their lives in freshwater and the other part in the salt water of the ocean. After multiple years feeding and growing in the open ocean, coho salmon nearly always return upstream to lay their eggs in the same place where they hatched. Standing redwoods shade creeks keeping the water cool while fallen trees help trap sediment and slow water flow, creating pools and hiding places for coho salmon. In return, salmon add important nutrients back into the forest’s soil. However, more than a century of human activities like logging and damming have led to a steep decline in the coho salmon population. Coho salmon are just one of the species that benefit from protecting and restoring redwood forests Learn more about our work to improve habitat for endangered coho salmon.

photo by Bureau of Land Management

Golden Eagle

Golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) are one of the largest and fastest raptors in North America. Diving at speeds up to 200 miles per hour or more, golden eagles prey mostly upon small mammals such as rabbits and ground squirrels – helping to keep populations balanced in the ecosystem. Building their nests in high places like the tree tops and cliffs of the Santa Cruz mountains, golden eagles are monogamous and will often return to lay eggs for several years.

photo by Rocky

Gray Fox

The only member of the canine family that can climb trees thanks to strong hooked claws, gray foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) are known to climb trees for fruit, birds and to evade predators. When climbing to safety isn’t an option, gray foxes can double back on their own footprints to try to throw predators like bobcats and coyotes off their trail. But as clever as these native foxes are, they have major competition from invasive red foxes that rely on similar depleting habitat and food sources. Gray foxes hunt small animals including rodents and rabbits, and will also forage foods like berries and insects. Diversifying their food sources not only makes gray foxes adaptable but lighter on the local ecosystem than their invasive red fox competitors which have made impacts on some bird populations in the Santa Cruz mountains.

photo by Colby Barr

Marbled Murrelet

Listed under the Endangered Species Act since 1992, the marbled murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus) is a rare and elusive seabird, under threat by oil spills, unsustainable fishing, and onshore habitat loss. Spending most of its life along the shores and only coming inland to nest and lay a single egg, the marbled murrelet faces the challenges of human impacts on both ocean and forest habitats. Marbled murrelets are small and chunky; they’re often described as a flying potato with a beak. For more than half the year, birds sport grayish feathers with black-dipped wings and heads; during breeding season, adults turn a mottled brown to help them better blend in with the forest canopy to evade predators. Marbled murrelets fly over the redwoods at dawn and at dusk en route to the ocean to catch fish, or to their hidden nest in redwood canopies. Learn more about the marvels and mystery of the marbled murrelet.

photo by Kim Nelson and Dan Cushing

Peregrine Falcon

A conservation success story, the peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus) nearly went extinct late in the 20th century due to shell thinning caused by the buildup of DDT and other poisons in the food chain. Today, peregrine falcons are rebounding thanks to the ban of DDT and full State protections, and nests along cliffs in the Santa Cruz mountains are being monitored by researchers. Diving at speeds recorded up to 242 miles per hour to catch their prey, primarily consisting of medium-sized birds like corvids which are known to steal eggs from the nests of other birds, Peregrine falcons are arguably the fastest animal on earth.

photo by Ron Knight

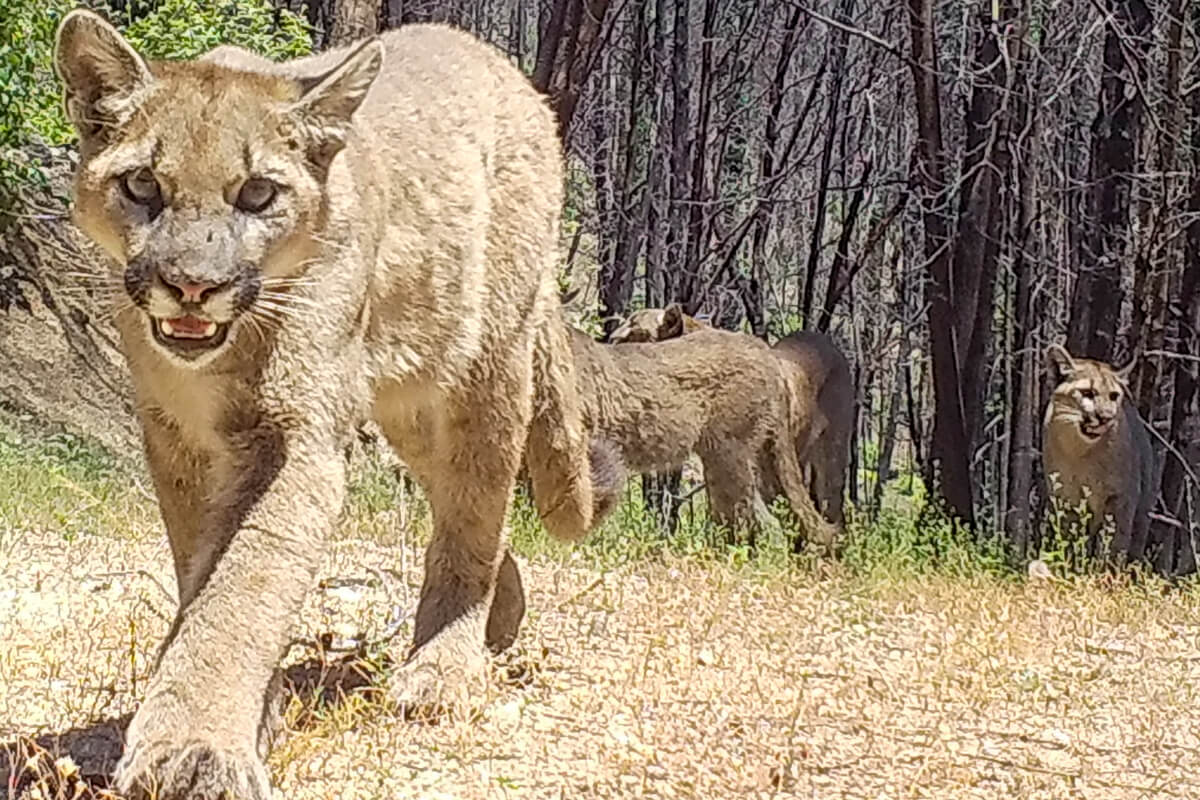

Did you know you’re more likely to be impaled by your own toothbrush than be attacked by a puma? Pumas (Puma concolor) are the native mountain lions and bobcats of the Santa Cruz mountains, also known as panthers, cougars, or catamounts. Pumas need extensive ranges for territory, hunting, and breeding – one reason why it’s so important to have large intact habitats with connected wildlife corridors. Roads and new development that fragment habitat are the biggest threats to pumas. Learn more about our work to conserve and expand puma habitat.

photo by Pathways for Wildlife

Red-tailed Hawk

Even if you haven’t knowingly seen a red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicensis), you’ve probably heard one. Their powerful scream is often used as a stand in for eagles and other raptors on television and movies. Named for their distinct tail coloring, their tail feathers are usually closer to a warm shade of brown than a vibrant red. Although red-tailed hawks can be seen soaring in circles above open fields and grasslands where they hunt, they typically nest in the crowns of tall trees like redwoods that offer great views of the surrounding landscape.

photo by Jaime Robles

San Francisco Dusky-footed Woodrat

Although our local subspecies is commonly called the San Francisco dusky-footed woodrat (Neotoma fuscipes ssp. annectens), they can be found here in the Santa Cruz mountains where they are among the region's great builders. In oak woodland areas, what might look like a pile of sticks on the ground or up in a tree, from the outside can actually boast multiple levels, and rooms with different functions including specific storage rooms for different types of foods and even an outhouse. These nests can be passed down for generations, with some thought to stand for 60 years, and are often connected to other nearby nests in their community by tiny trails. Their well-built nests provide vital shelter to many other small creatures in the Santa Cruz mountains including salamanders, snakes, lizards, mice, frogs, and insects.

photo by Santa Cruz Mountains Bioregional Council

Santa Cruz Black Salamander

Although they live on land, the Santa Cruz black salamander (Aneides niger) doesn’t have lungs. Instead they breathe through linings in their mouth and through their distinguishable nearly uniform black skin which can also secrete a sticky substance for self-defense. Breathing like this requires the salamanders to be in moist environments near water but not in the water. This makes them well-suited to the redwood forests and riparian of the Santa Cruz mountains. So well-suited in fact, the Santa Cruz black salamander doesn’t exist anywhere else. Protecting habitat for this California Department of Fish and Wildlife Species of Special Concern is crucial as habitat loss due to development and climate change makes the region hotter and drier and threaten its ability to survive and play its role eating invertebrates like millipedes and termites in the redwood forest.

photo by Ken Ichi Ueda

Southwestern Pond Turtle

The Southwestern pond turtle (Actinemys pallida) is the only turtle native to the Santa Cruz mountains region. While Western pond turtle populations plummeted by roughly 50% in 2014 when scientific research recognized they were actually two distinct species, Northwestern and Southwestern pond turtles, Southwestern pond turtle numbers have continued to decline due to freshwater habitat loss, invasive turtle and bullfrog species, and climate change. Like many other turtles, the gender of Southwestern pond turtle hatchlings is affected by the temperature of the nest while the eggs are incubating and nest temperatures above 85 degrees Fahrenheit can tip the scales allowing for fewer mates. We are working with specialists to learn how this California Species of Special Concern might be supported by protected habitat and stewardship in the Santa Cruz mountains.

photo by Jeffrey E. Lovich, USGS

Did you know steelhead trout are actually in the salmon family? And like Coho salmon, steelhead trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) are anadromous, spending about half their lives in the ocean’s saltwater and coming back to the freshwater they were born in to spawn the next generation. Although being able to survive in both fresh and salt water is already pretty rare, steelhead trout are truly unique because they develop based on their environment. Steelhead and rainbow trout are actually the same species, the only difference is their lifestyle. After being born in gravel-covered freshwater beds of streams and rivers, steelhead migrate out to the Pacific Ocean where they typically grow larger and more steely colored than their rainbow trout relatives who remain in freshwater. Steelhead trout are threatened throughout their habitat range in a large part due to blockages like dams and culverts that prevent them from returning to the freshwater they need to spawn. We’re working to restore a critical watershed, once blocked by an ancient dam, so rare and unique steelhead trout can thrive in the Santa Cruz mountains again. Watch a steelhead in Mill Creek just downstream from the newly removed dam.

Photo by NMFS/Southwest Fisheries Science Center; Salmon Ecology Team

Steller's Jay

One of the most brightly-colored native creatures in the redwood forest next to the banana slug, blue-feathered Steller’s jays (Cyanocitta stelleri) will be sure to catch your eye and your ear. Although they are technically songbirds, they are generally considered quite noisy making not only their own “scolding” calls but also imitations of other animals and even reportedly some mechanical objects. These smart and curious birds enjoy evergreen forests like the redwoods of the Santa Cruz mountains, and can often be seen along trails, picnic grounds, and campgrounds because they don’t want to miss any opportunity for meal. Unfortunately, meals for these and other corvids can include stolen eggs from other bird’s nests like the endangered marbled murrelet which nests in old-growth Douglas-fir and redwood trees in the Santa Cruz mountains. You can help keep bird populations wild and balanced by keeping crumb clean when you’re outdoors. We’ll be continuing corvid surveys at San Vicente Redwoods to monitor how public access there might impact populations of birds like Steller’s jays.

photo by KaddiSudhi

Townsend’s Big-eared Bat

Of the diverse species of bats found in the Santa Cruz mountains, the Townsend’s big-eared bat (Corynorhinus townsendii) is the most rare and impacted that has been detected at our San Vicente Redwoods property where ongoing bat research led by Dr. Winifred Frick with Bat Conservation International is taking place with unobtrusive audio monitoring equipment. Plus, as our Land Team points out, they’re adorable. While considered a medium-sized bat, the out-sized ears for which they’re named are not. In fact, their ears can be half the length of their bodies. Their sensitive ears may play a role in their listing as a sensitive species. Unsurprisingly, their big ears are hypersensitive and roosts of Townsend’s big-eared bats will wiggle them around to try to identify an intrusion and will often fly away never to return. This may make them highly-susceptible to human disturbance which could drastically limit suitable habitat and can make research challenging. This California Species of Special Concern has been known to roost in large basal hollows of redwoods as well as caves where they are important members of the ecosystem keeping insect populations under control.

photo by National Park Service

More to Explore

- Check out our introduction guide to Birds and Birding in the Santa Cruz Mountains

- Learn more about how we monitor wildlife for healthy forests

- Read about how we’re restoring Mill Creek for wildlife