Awakening of the Silent Forest

photos by Ian Bornarth Photography

My introduction to the effects of this fire was a trip to Big Basin Redwoods State Park in September 2020. Somehow I had expected much worse. While there was significant damage to the forests, there were areas that look like they would come back pretty quickly. Most of the park buildings I saw had been completely destroyed. There was still a strong odor of wood smoke in the air as there was still smoke coming from some of the charred trunks. The amount of debris and fallen trees was astounding, with large branches everywhere.

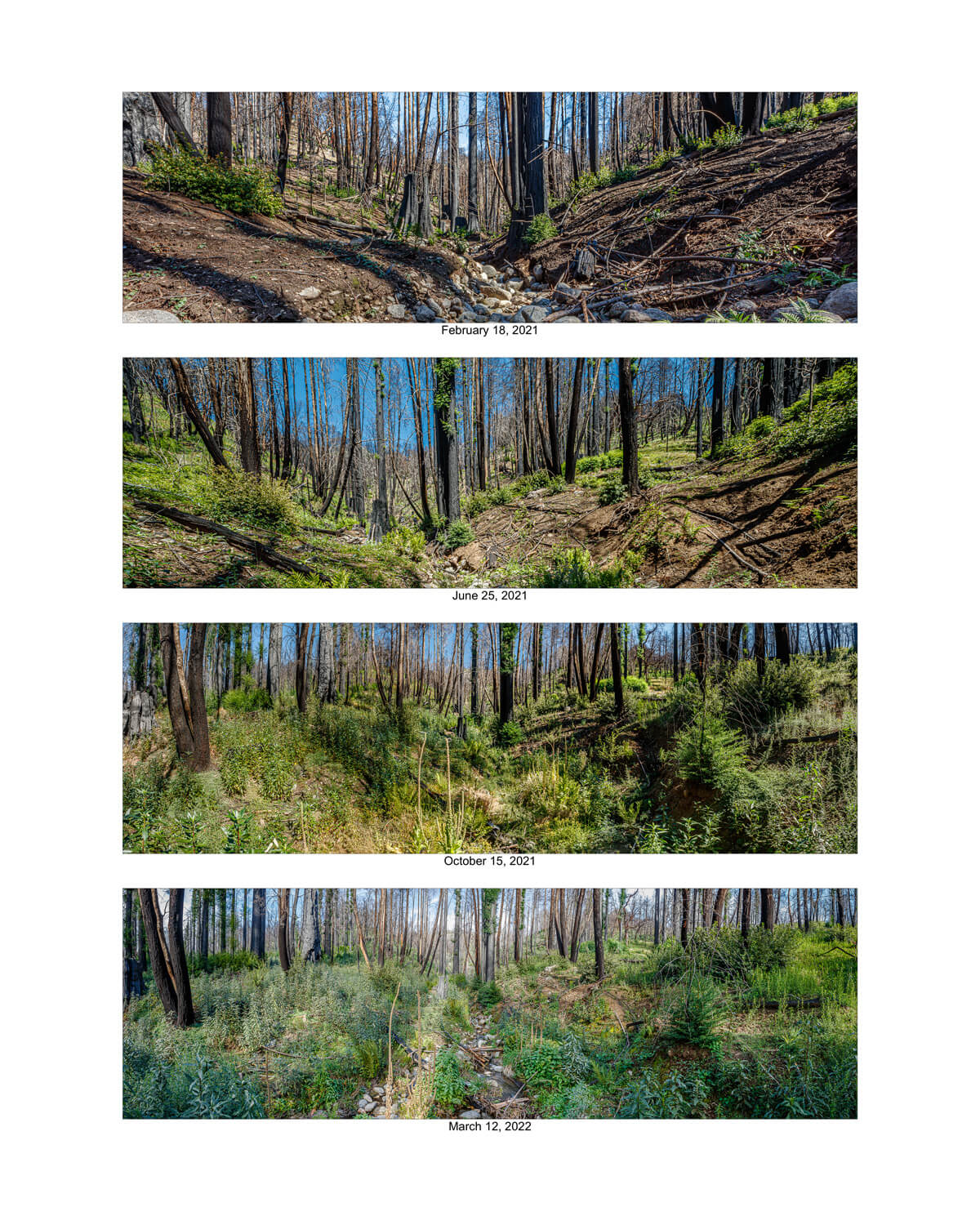

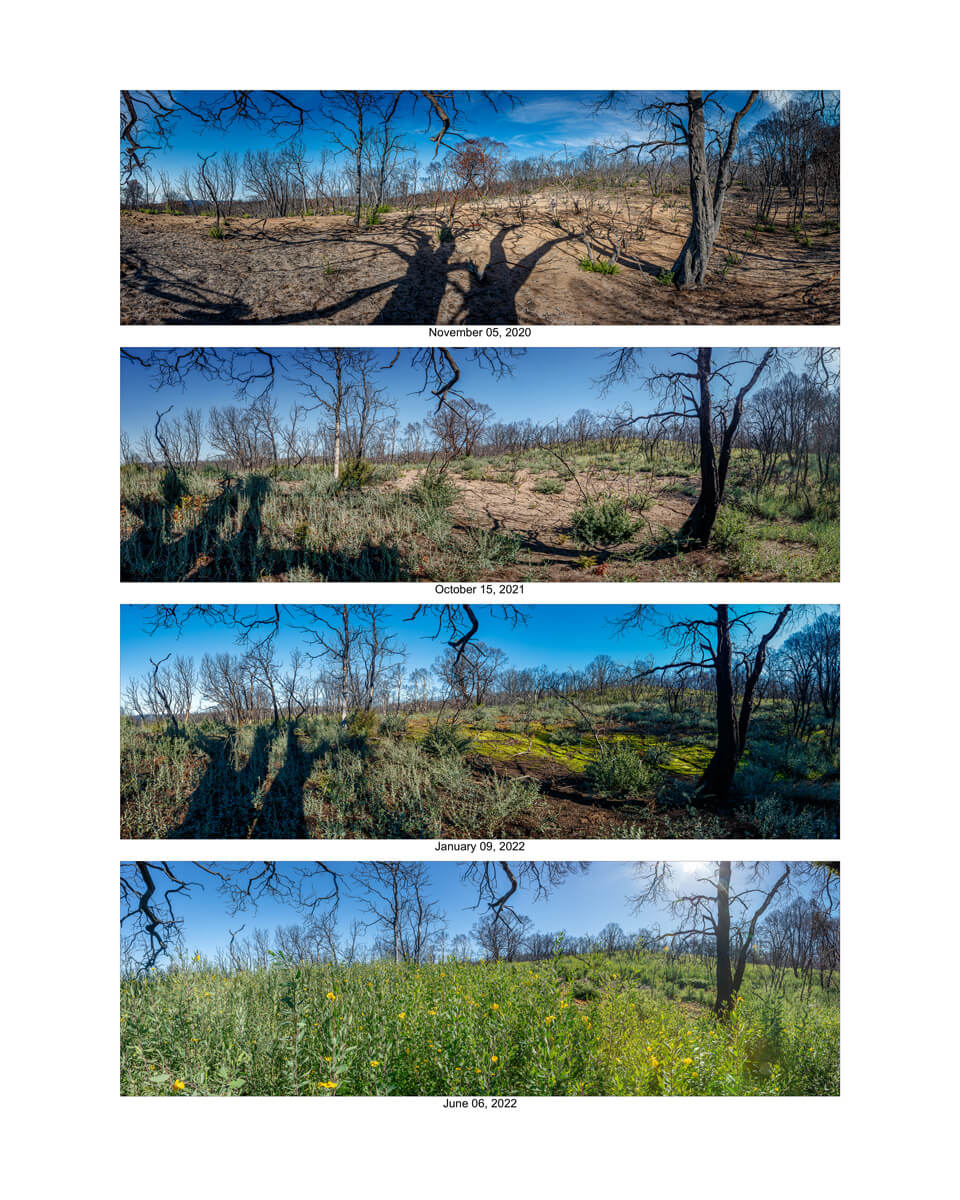

My second trip in November allowed me more time to comprehend what had happened as I was able to see additional areas. There was already a significant effort going on to clear roads and debris. The first trips into some of the other highly affected areas, like San Vicente Redwoods, were in October and November 2020. I found a stark grey landscape of dusty soil, burned trees, and little to no underbrush. The ash and dust on the ground had a fine consistency and fluffed out around our footsteps as we walked.

However, I also found the beginnings of new growth. These forests were nearly silent except for the wind and the occasional clatter of branches. In some areas there was a layer of brown needles, leaves and broken branches covering the ground. In others, the ground was almost bare, swept clean, leaving only ash and dust.

On one trip to the ridge lines high above Gazos Creek, I gained a much wider view of the extent and impact of the fire. Looking in all directions, ridge after ridge and valleys in between were burned. Leaving only pockets of spared trees and thousands of charred acres of blackened trees in a monochromatic landscape. It was encouraging to see small plants, including the occasional wildflowers coming up between the charred tree trunks and the ash covered ground.

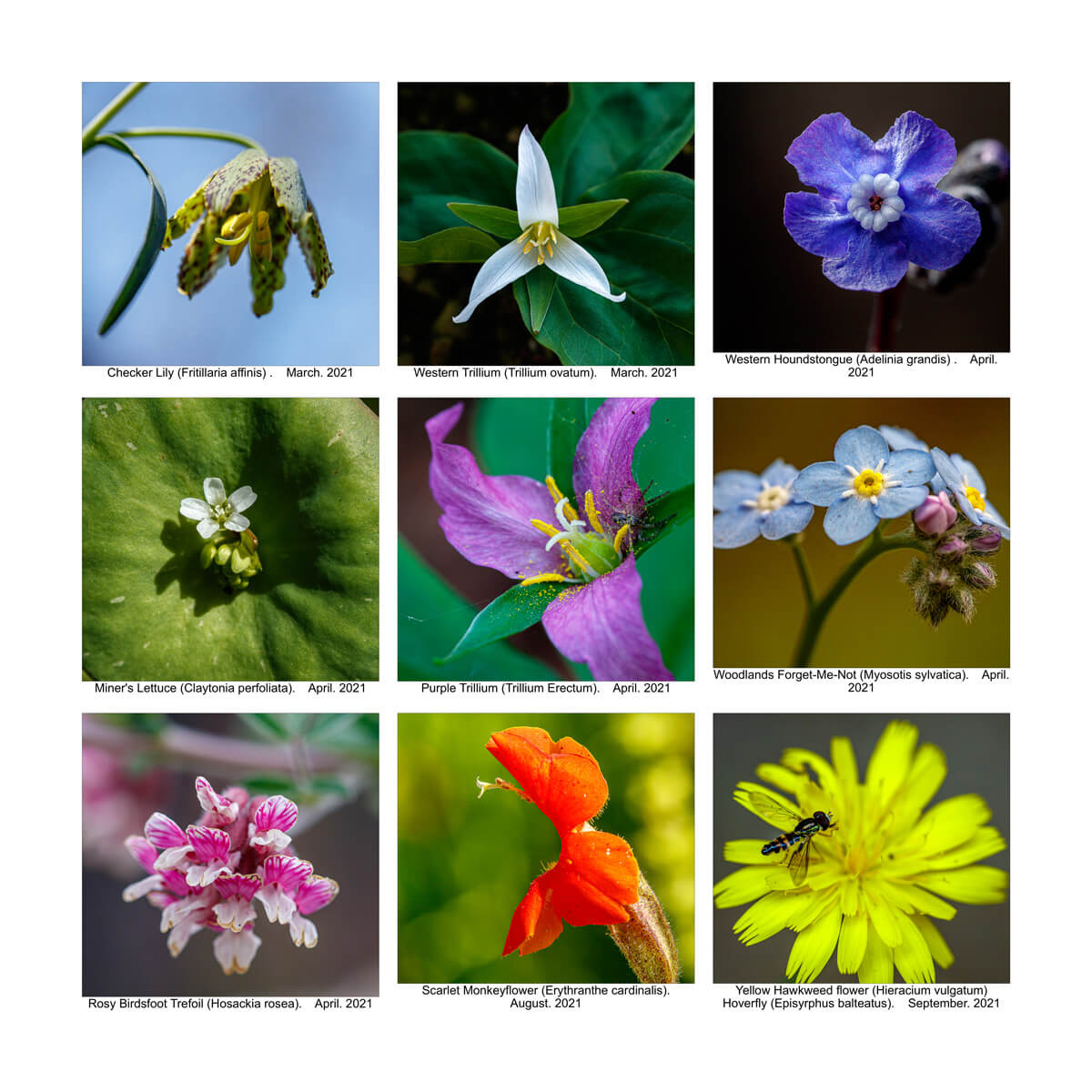

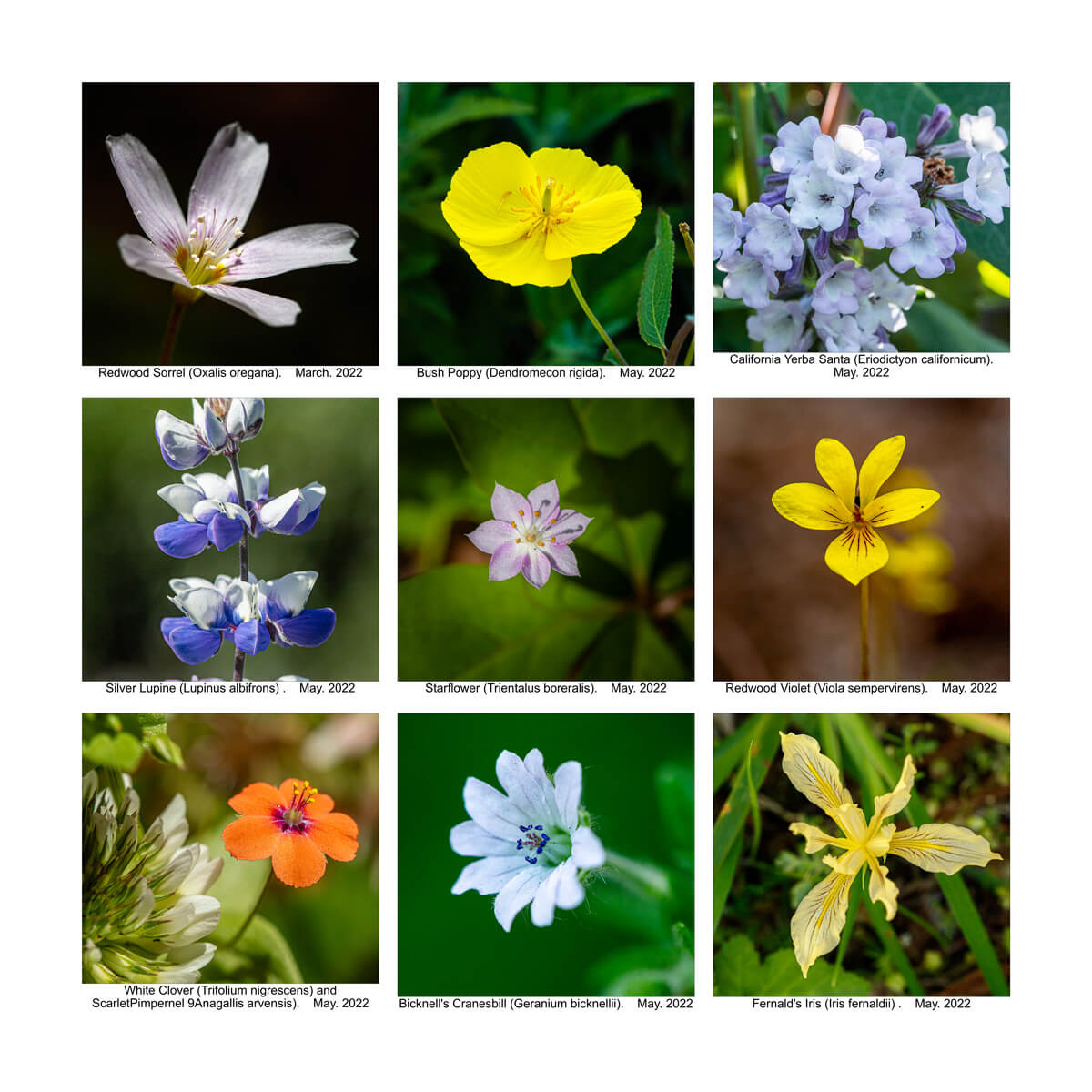

Throughout the winter of 2020/2021, the rains came and went, filling the streams. One large storm scoured the creek beds and eroded hillsides. Loose soils allowed trees to fall. Creek beds and sediment were rearranged. By mid-winter, ferns and smaller plants were starting to emerge and the occasional animal tracks were found. Redwood trees had begun to sprout along the length of their trunks while dead trees started to lose their bark and smaller branches. The forests were still very quiet. There were still very few insects, birds or other animals. Into the spring, with more rain and sun, more small plants and mushrooms emerged and wildflowers were becoming plentiful. This brought back the buzz of bees and flittering butterflies. In some of the less severely burned areas, smaller animals, such as newts and banana slugs, were found.

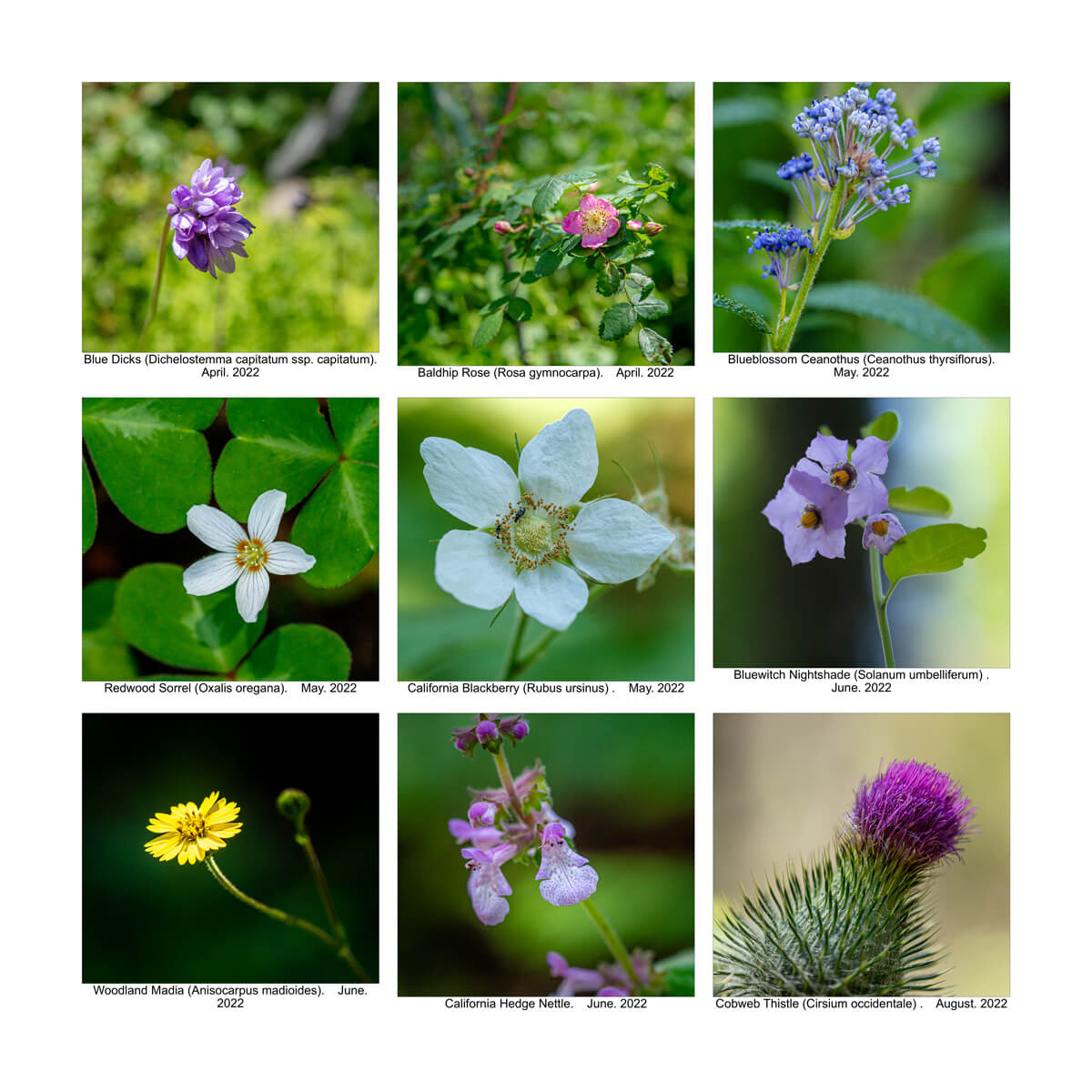

During the first summer, plentiful sun spurred growth of the understory as more ferns and more wildflowers appeared, including irises, lupine and many others. The seed bank in the soil was sprouting to life again. The calls of birds were becoming plentiful again. However, some areas that were severely affected were still barren and stark with little growth as the return of life was not evenly spread. Animal tracks were becoming more plentiful in some areas as well. The new growth offered a lively contrast against charred tree trunks in the recent burn scars.

Even after months of rain and sun, the forest was still very dry with sparse growth. Ferns had come and gone, even the poison oak seemed to grow slowly.

As the rains returned in the fall of 2021, the valleys became greener. More rains fed the regrowth. Mushrooms and other fungi were becoming plentiful again. Larger animals and birds were becoming more apparent. Some of the areas that hadn’t been severely affected were looking almost normal aside from the occasional shared stump or newly fallen tree. In December that year there was a large storm that sent surges of water down creeks, carrying large logs and stumps downstream and reorganizing stream beds in the process. Through the winter of 2021/2022 and into the spring, there was an explosion of growth. It was as if the entire forest was trying to come back all at once. Wildflowers were abundant, as well as many layers of animal and insect life. The sounds of water in the streams and the calls of birds followed the valleys. The fresh smell of the forest was returning.

As summer started once again, some areas became thick with undergrowth. Other places that were not as affected continued in more normal patterns of growth. I found that returning to some of my usual sites was becoming difficult due to dense growth. By late summer, I had to push my way through tight groups of field poppies, poison oak and sprouting manzanita trees. It was amazing to see so many of the yellow flowers. This was an area that had been severely burned in one of the highest areas of the San Vicente Redwoods.

Fall took over and the once monochrome forests were looking alive with color again. High up the redwoods were countless bright green sprouts. While the canopy will take some time to fill in, plenty of sun will encourage additional new growth on the forest floor. It was now easy to see which trees had survived and which had succumbed to the fire. The dead trees will be future homes to countless animals and birds until they fall and eventually rejuvenate the soil. On more recent trips I began to see more evidence of animals including scat and tracks in the soft soils.

After more than two years, 2022 ended in spectacular fashion with a procession of atmospheric rivers and record rainfall. Parts of the Santa Cruz mountains received close to three feet of rain in those weeks. The water inundated valleys, tearing at the soils and streams and sending the debris rushing to the sea. While the water was greatly needed, so much so fast brings its own changes.

Through the winter and spring of 2023 huge amounts of rain fell in the form of a succession of atmospheric rivers. All the water fueled a tremendous amount of growth across the region. It also tore at the streams, carving new and deeper channels. The winds and saturated soils brought down many trees. By the end of spring there were large amounts of logs and stumps on the coastal beaches and whatever debris didn’t reach the ocean created woody debris piles throughout the many of the stream systems. While we often view these storms as destructive, they are really just one part of an ever-changing environment.

During all that time, I watched the layers of the ecosystems rebuild themselves after this devastating fire. While I know that it will still take many years for the forests to more fully recover, it is amazing to witness a new beginning. So often, we see the fires but rarely the environmental processes afterwards. We forget how gradual the process is.

Gallery

Looking for more? You can zoom in and explore each of photographer Ian Bornarth's curated photos in chronological order to witness the resilient redwood forests of the Santa Cruz mountains resurge with life over three years of recovery since the region's most devaststaing fire on record, the 2020 CZU Fire.

More to Explore

- See even more of Ian Bornarth's stunning image's of the forest's recovery from fire in his gallery

- View the challenges of caring for a forest recovering from fire while preparing its next in Fuel for Fire

- Read more about fire and stewardship in Redwoods and Climate Part 3

- Read more about how long the forest's recovery may take in Nature Needs Time to Heal