Conservation, Eco-Ableism, and Reclaiming Limitations

photo by Orenda Randuch

For far too long, our world has been shaped by ideologies that both imagine, mark, and limit certain bodies for inclusion and exclusion from public space and the greater natural world. Although ableism, racism, and settler colonialism are deeply intertwined and difficult to separate, I focus specifically on the role of ableism in the outdoors, an intersection often termed eco-ableism. Eco-ableism is a core component of the creation of public lands.

Redwoods are an excellent example of how limitations are ignored within the natural world. Redwoods are uniquely adapted to grow into the tallest trees on earth, but even the coast redwood can only grow so tall, limited by the capacity of all trees to carry water and nutrients upwards into the tree’s crown. Scientists estimate that the maximum height of a redwood is 427 feet, though climate change is limiting this growth as the forest dries and warms.

Syren Nagakyrie (left of center in the green shirt and white face mask) and members of Disabled Hikers on a hike in Reinhardt Redwood Regional Park, photo by Orenda Randuch

photo by Orenda Randuch

The redwoods are celebrated because of their awe-inspiring size, age, and ecological functionality but, until recently, their limitations have largely been ignored by White-centric conservation efforts. The less grandiose beings of the redwood forest have also been ignored—the mycelium that forms connections throughout the forest, the salmon that feed the forest, the slugs and the moss and the billions of tiny microbes that are critical to a holistic ecosystem.

This tendency to focus on the remarkable affects disabled people as well. It contributes to expressions of the spaces disabled people can and cannot inhabit as a type of ableism, which describes discrimination against people who are disabled and the constructed bias towards bodies that are perceived to be whole, natural, and productive. For example, you may be familiar with “inspiration porn” a term coined by Stella Young to describe the objectification of disabled people as simultaneously bad and exceptional, and sources of inspiration for “overcoming” their disabilities.

In this way, society perpetuates ableism by uplifting certain stories of exceptionality and remarkableness, while also dehumanizing disabled people’s bodies as atypical and an impairment that must be overcome.

Early Conservationism and Intentionally Limiting Accessibility

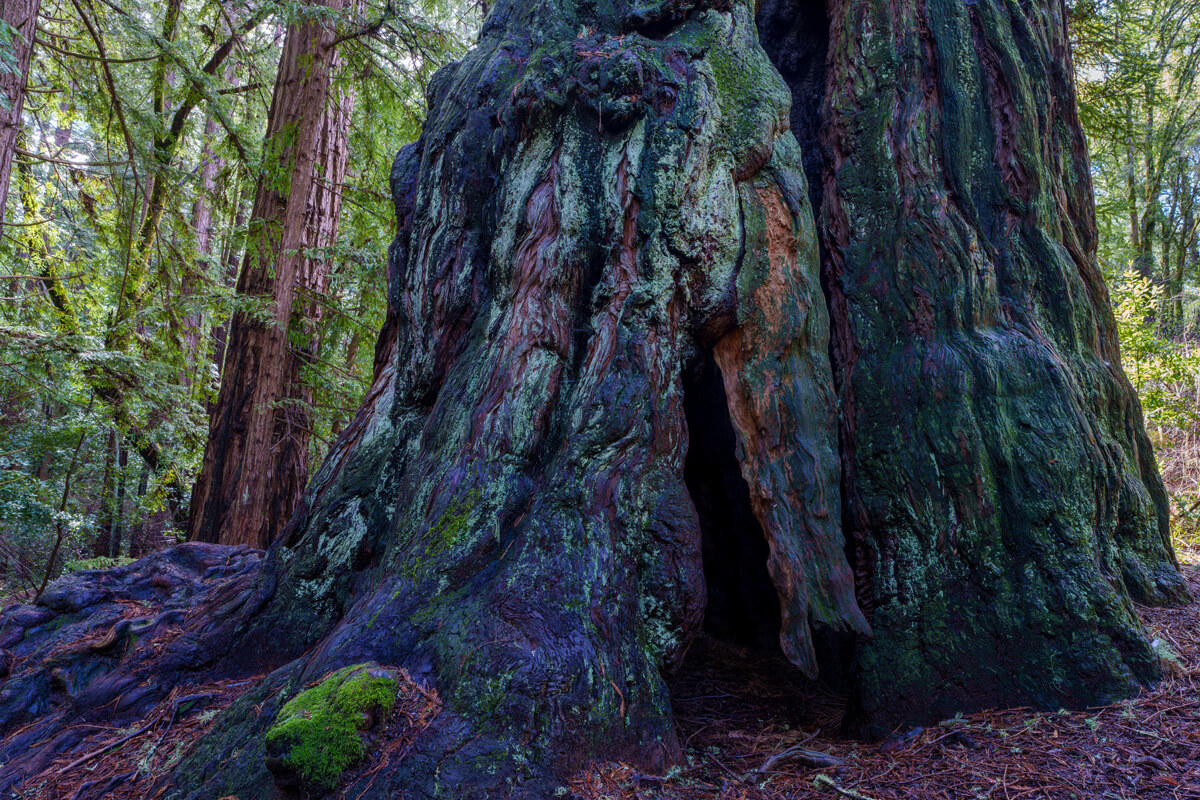

When we focus only on the most remarkable and inspirational, we miss so much wisdom about the intricacy of nature and how we define and conceptualize limitation. Disability becomes acceptable only in the context of overcoming limitations; otherwise, it remains unnatural. Unfortunately, these ableist ideas about disability were also held by the early conservationists, and greatly influenced the founding of the wilderness and conservation movements. Ironically, many of the old growth that we revere as majestic only stand today because in the eras of clear cutting they were deemed unharvestable for timber. They were undervalued as mercantile because of their perceived flaws: a twisted trunk, burls and knobs, or reticulating limbs.

A particularly burly old-growth redwood trunk with a basal hollow, photo by Orenda Randuch

Environmentalism and adventure culture rose out of the “wilderness cults” (Ray, 2017), a specific organized movement of Whiteness in the wilderness, where encounters with raw nature created a sense of personal purity and grace. Wilderness was promoted as a source of moral, racial, and national purity, and there are many early documents referring to conserved lands as a place of refuge from racial and social anxieties of the time. This continues today, where race, class, and gender exclusion is perpetuated under the banner of “protecting” the wilderness, informing decisions about which lands to protect, and often restricting access only to a few (often privileged, wealthy, and White) communities.

Railing along trails can impede hikers' line of sight, photo by Orenda Randuch

This exclusion applies to disabled people as well. The Wilderness Act excluded disability because of the emphasis on encounters with “raw” nature as ideal. (Although the act has been interpreted to mean that wheelchair use is not explicitly excluded from wilderness areas, agencies are also not required to make improvements to enhance accessibility, even under the Americans with Disability Act.). People who engage in wilderness activities are often considered to be more attuned to the natural environment through these physical experiences, but the bodies that can have these experiences are typically White, fit, cisgender masculine, and able-bodied.

These bodies have been a part of the forced narrative of who engages with the outdoors since the creation of public lands. That narrative has been reinforced through representation in marketing and gear designed for their use, and support for them as the dominant voices in conservation and recreation planning. This means that White, fit, cisgender masculine, able-bodied people can trust that public land access and recreation has been constructed with their needs in mind, and report feeling the safest on trails.

Bodies that cannot engage in this way—who can’t experience nature without technology or structural changes, or who do not feel safe in outdoor spaces—are considered unnatural and un-environmental. The unspoken idea is that disabled people can’t truly care about the environment because they can’t experience it, and therefore they are also impure and morally inferior.

This may not be your experience, but I can guarantee that it happens more than you think: people say things like “we can’t build paved trails” or “hiking isn’t for disabled people!” or “developed trails / wheelchairs / cell phones / or speakers” ruin my experience, and what they are implying is that anyone who does not have the ideal body is a threat to their identity as a hiker and to nature overall. But having a solitary retreat in nature, or a deep immersion unmediated by technology, is not the only way to truly engage with the environment.

There is also the false assumption that disabled people do not want to be outdoors or recreate on public lands because our bodies prevent the “correct” experience. The idea is that the outdoors is inherently inaccessible due to natural features, and therefore if disabled people do want to be outdoors, it must be made accessible for us, usually through making special changes to the built environment. Again, we come up against the idea that disability is un-environmental—that any changes to the built environment negatively affect the natural environment. But this is not true. It has been proven many times that accessibility improvements can reduce the ecological impact that all bodies have on the environment and surrounding areas. For example, paving a popular trail and installing overlooks improves safety and reduces off trail use, and improving trail grade and surface improves soil conditions and reduces run-off. What people fail to acknowledge is that trails, roads, and other features that make public lands accessible to them already have an impact on the environment—this impact is just normalized and accepted.

Members of Disabled Hikers utilize different mobility devices on their hike, photo by Orenda Randuch

Accessibility is not limited to people with disabilities. Everyone has access needs, especially in the outdoors. Non-disabled access is normalized and invisible, while disabled access is “special” and hyper-visible: Why are ramps and paved trails more controversial than the fact that a trail exists there at all? Why is climbing with ropes or hiking on ice with crampons considered “hardcore” while using an e-bike or a mobility walker to access trails is considered “weak?” I don’t believe that every trail or experience has to be accessible to every body, even non-disabled bodies. Limitation is natural, and no one can do everything. But recreation areas on public lands are all constructed to some extent, which means that it is a decision to exclude disabled people. Accessibility is not all or nothing, and access needs vary so widely—there is no one size fits all solution, and sometimes even the smallest change can have a major impact.

photo by Orenda Randuch

For example, providing detailed, accurate, and objective information about trails allows disabled people to make informed decisions about whether a trail is accessible to them or not, without relying on non-disabled people to make that decision for us. Installing a bench or an accessible picnic table provides an opportunity for people to rest and a destination to enjoy being outdoors. Creating multi-sensory experiences, such as audio description units and tactile exhibits, enhances learning for a wide range of people while also increasing accessibility.

photos by Orenda Randuch

Although it is important to address physical barriers and lack of access, the outdoors won’t truly be a safe and inclusive space if we do not also address ableism and long-held assumptions about disability. We could build accessible trails in every park—but we must also move away from the idea that the most valid way of being outdoors is the individual “conquering” nature, and instead move into respecting the variety of ways that people engage with nature and recognize that this provides an opportunity to reflect on interdependence and the relationship between our bodies, the environment, and each other.

It is so important to consider the variety of ways that bodies exist in nature, the incredible diversity of senses and sensory experiences, of ways of moving through the world, of places where animals exist and have become adapted to. Because the ways that my body exists, moves, and interacts with the environment are just as natural as every other body.

Syren Nagakyrie (they/them) is the founder of Disabled Hikers, a Disabled-led organization building disability community and justice in the outdoors. They are also the author of The Disabled Hiker’s Guide to Western Washington and Oregon (2022, Falcon Guides) and The Disabled Hiker’s Guide to Northern California (2024, Falcon Guides). They work throughout the West Coast and further afield to improve access, representation, and belonging for Disabled communities.

More to Explore

- Join Syren Under the Redwoods for a discussion of how the disability community is building a future outdoor recreational culture centered on representation, access, and justice

- Check out Accessible Trails in the Santa Cruz Mountains

- Join the Reimagining Big Basin process to help Big Basin Redwoods State Park be accessible to every body