Redwoods and Climate Part 3

Impact of climate on redwoods by Ink Dwell studio

The Impacts of Climate on Redwoods: Part 3

Cut by deep valleys, cooled by the sea breeze, and draped in fog, the Santa Cruz mountains are a southern stronghold for California’s coast redwoods. The range’s oldest trees have withstood nearly two millennia of drought, floods, winds, fires, earthquakes, and changes made by the area’s human residents.

In the third part of this new series by Julia Busiek, Sempervirens Fund explores how Earth’s constantly changing climate shaped redwoods over millions of years, how human-caused climate change is affecting redwoods today, and what the future holds for the iconic forests of the Santa Cruz mountains.

The Past, Present, and Future of Fire and Stewardship

On July 22, nearly two years after the CZU Complex fires torched 125 square miles in the Santa Cruz mountains, Big Basin Redwoods State Park welcomed its first visitors back to a landscape transformed. Over 90% of the park’s redwood trees survived the intense blaze, but few emerged unscathed. Most bear blackened trunks, and many lost their massive, shade-giving crowns, so the sun shines with full force on the forest floor carpeted with electric green shrubs and grasses. All the park’s campgrounds remain closed, along with most of its roads and trails. Electricity, communication lines, and drinking water have yet to be restored. A stone staircase in the corner of a clearing is all that remains of the visitor center.

For the loved ones of the person who died, the 900 people who lost homes, and the millions with abiding memories of the way the forest of the Santa Cruz mountains looked, felt, and smelled before it burned, the CZU fire was an acute and painful wound. But though the fire spread with astonishing speed and burned most of its eventual footprint in just a few terrifying days, experts say the conditions that generated the blaze have been building since the earliest years of European colonization.

“When I took this job, I knew fire was coming,” said Sempervirens Fund Executive Director and California State Parks and Recreation Commissioner Sara Barth. “We all knew. It was just a matter of time, and how bad it would be when it came.”

How did we get here? What caused so much land to burn so intensely in such a short time? And what, if anything, can be done to prevent it from happening again?

Sara Barth at Big Basin Redwoods State Park after the CZU fire in 2020, by Ian Bornarth

The Roots of the Problem

Flames cast an orange glow on massive plumes of smoke as the CZ fire burns on Butano Ridge, by Inklein

Climate change is perhaps the CZU fire’s most obvious culprit. The winter before the fires, Santa Cruz had received just half of its average annual precipitation, and on August 16, 2020—the day the fires ignited—the temperature in Santa Cruz hit 107 degrees, more than 30 degrees above average. “Climate change is certainly increasing the frequency, severity, and duration of extreme heat and warm nights,” Flavio Lehner, a climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, told the Los Angeles Times in a story published that day. “It is safe to assume that climate change contributed to the extreme nature of recent events.” Those conditions put the whole landscape closer to its ignition point when a rare lightning storm that evening sparked fires throughout the region. Some of these ignitions smoldered for two days until fierce winds and high temperatures fanned the flames into a running inferno on August 18.

But many fire experts agree that climate change isn’t solely to blame for the speed, severity, and extent of the CZU fires. “Yes, it was a drought, but the CZU complex did what it did because the forest structure enabled it,” says Scott Stephens, who leads the Fire Science Laboratory at UC Berkeley. “People have been suppressing fires in that area for over 120 years, and that’s led to a completely changed fuels complex compared to what you’d have seen a few hundred years ago.”

For thousands of years before Europeans arrived, the Mutsun- and Awaswas-speaking people who lived in the Santa Cruz Mountains used fire as a maintenance strategy. Frequent, targeted burns encouraged fire-dependent species like oak, whose acorns are an important source of food, and white root sedge, used for making baskets. Frequent burning also kept brush and trees from crowding out coastal prairies where abundant wildlife—many of them game species—flourished. And fire cleared out downed trees and dense understory, killing pests and making it easier to walk across the landscape.

This frequent, targeted, low-intensity fire shaped a landscape with fewer, larger trees, spaced further apart, without as much brush or built-up debris as is typical of forests that go decades between burns—the kind of forests, Stephens says, that predominated in the Santa Cruz mountains on the eve of the CZU fires. “I used to hike and camp at Big Basin and walk all around that place a lot,” Stephens said. Occasionally, he’d come across patches where State Parks staff had ignited controlled burns. “But the vast majority of Big Basin had never had any fire for decades—I’m talking 50, 60 years in a lot of cases.”

Smoke rises from fire darkend soil, free of brush and other "fuels", below undamaged canopies after a cultural burn on San Vicente Redwoods, by Mike Kahn

The hazardous decrepitude of the region’s forests is, in some ways, among the catastrophic consequences of California’s colonization by white people. Beginning in the late 18th century, Indigenous people in the Santa Cruz mountains endured successive campaigns of violence, genocide, and cultural destruction. First under the Spanish mission system, then the Mexican ranchero era, and beginning in 1850 at the hands of the United States and California governments, Indigenous people have been removed from their homelands, exposed to unfamiliar diseases, enslaved, and killed. UCLA Historian Benjamin Madley estimates that the Indigenous population of California dropped from 150,000 to 30,000 in the 25 years after gold was discovered in the Sierra Nevada in 1848.

Alexii Sigona sits atop a stump in a forest recovering from the CZU fire damage on San Vicente Redwoods, by Jason Jaacks

“With land dispossession, we lost the capacity or opportunity to steward our traditional lands for ourselves, the animals, and the plants. That is part of the intergenerational trauma inflicted on our people—it’s a disconnect from who we are,” says Alexii Sigona. He’s a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management at UC Berkeley and a member of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band. The band’s 600 members are descendants of Indigenous people who were forced to relocate to the Missions San Juan Bautista and Santa Cruz during the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Sigona’s research explores the legal and regulatory mechanisms—like conservation easements, memoranda of understanding (MOUs) with landowners, and the California Environmental Quality Act—that the Amah Mutsun Band can use to protect Tribal cultural resources and regain access to and stewardship of lands within their traditional territory. “Returning to the land is part of healing for our people,” Sigona says. “When our stewards are able to get out on land, I’ve known people who’ve become free of addictions, mental health issues, and other things like that.”

In 2014, Sempervirens Fund backed the Tribe’s efforts to establish the Amah Mutsun Land Trust. Sigona is an alum of the organization’s Native Stewardship Corps, which trains young members of the Tribe in disciplines like cultural burning—using fire to stimulate the growth of culturally important plants—as well as forestry and ecology. Today, the land trust and its growing roster of experts hold two conservation easements, MOUs with six local land management agencies, and contracts for controlled and cultural burning across their traditional homeland.

“We believe that the Creator put us here for a purpose. We’re here to take care of Mother Earth. The core part of who we are culturally is to put our hands in Mother Earth, care for it, and to help it heal,” Sigona says. “We’re not interested in owning Mother Nature, but in fulfilling our obligation to our Creator to steward these lands.”

Wilderness Wisdom

To put it mildly, the Amah Mutsun’s quest to restore connections to their ancestral lands contrasts with European and American attitudes and assumptions that have shaped the past 200 years of land use in the Santa Cruz Mountains. From the mission era onward, white people prohibited the region’s Indigenous people from practicing many of their cultural traditions, including burning. “Not only did Europeans displace the Indigenous people and therefore interrupt the cycles of indigenous burning that had been happening for millennia but they also suppressed all additional fires that might have been ignited by lightning or other sources,” Barth says. “So you have this long period of fire suppression, which leads to a huge buildup of fuel.”

The Gold Rush sparked a population boom throughout the state—and marked the beginning of the end for most of the ancient forests on the Santa Cruz Peninsula. In the second half of the 19th century, loggers clear-cut nearly all of the range’s redwoods, seeking timber to build the growing cities on the bay’s shore. It was out of this frenzy, Barth says, that the Sempervirens Fund was founded in 1900. (The original name was the Sempervirens Club.) The organization helped establish Big Basin as a California state park in 1902, protecting six square miles of as-yet-unlogged redwoods. Since then, Sempervirens Fund has protected 35,000 acres throughout the southern Santa Cruz mountains, a mix of old growth and previously logged forests.

Amah Mutsun Land Trust Native Stewards perform a cultural burn ceremony at San Vicente Redwoods, by Mike Kahn

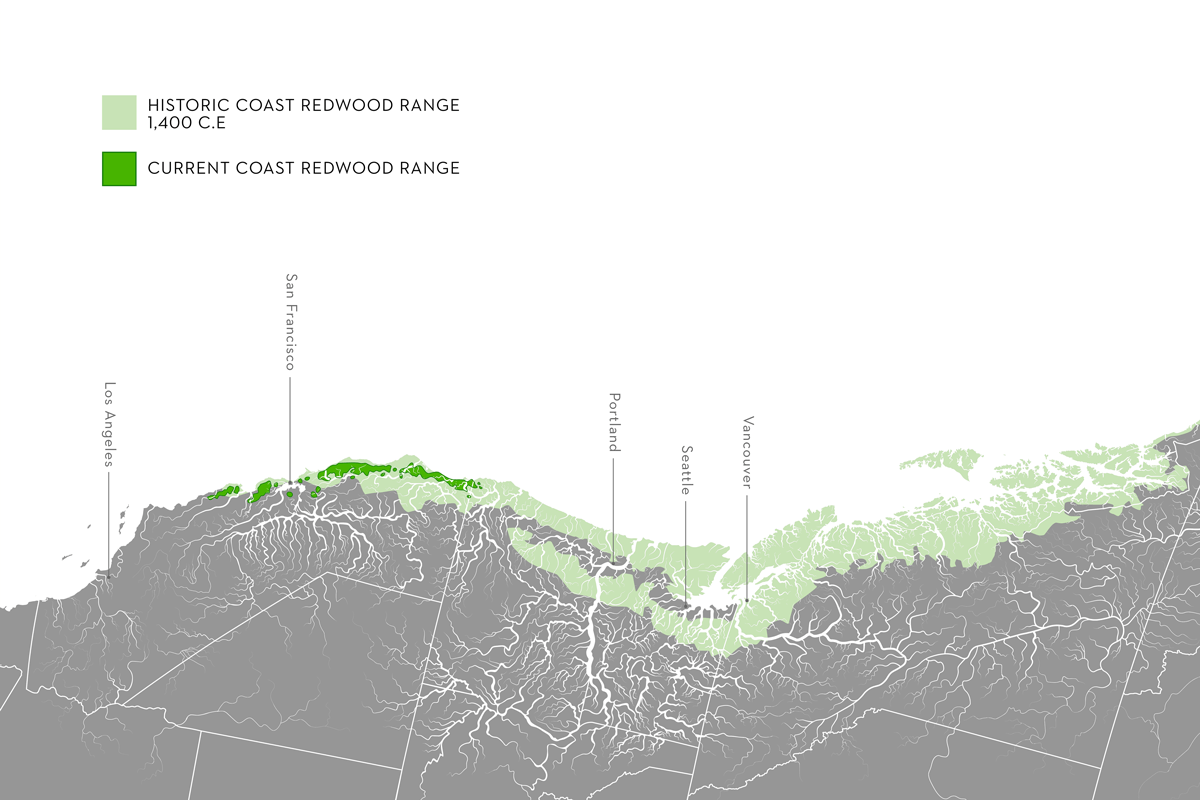

Present Versus Historic Coast Redwood Range Map, by Jane Kim, Ink Dwell

“I think the founders were driven primarily by their concern at the rapid loss of forest they were witnessing, and a recognition that these trees were a majestic, incredible, and finite resource,” Barth says. “That was opposed to the dominant mindset at the time, that this was a forest range that was so vast that it would never be ‘conquered,’ if you will.” The decisive action from Sempervirens Fund’s early members, and continued support from subsequent generations of donors and partners, is one of the main reasons the Santa Cruz mountains has any old-growth redwoods left at all. For over a century, visitors from the Bay Area’s ever-expanding cities drove past miles of clear-cuts and homesteads to reach the boundaries of Big Basin—a place where nature was protected instead of exploited for profit, and where the forest could be left to take care of itself instead of being managed for maximum harvest.

But here in the Santa Cruz mountains and around the world, the idea of wilderness as pristine and untouched by humans has undercut natural systems that evolved with at least some, and often a great degree of, human influence. “I do know people who are pretty noisy about their belief that actively managing natural areas is unnecessary,” Stephens says. “But that attitude totally discounts the impact of millennia of Indigenous stewardship.”

An ancient oak at San Vicente Redwoods, by Mike Kahn

Stephens recalled a visit to a stand of “the largest oaks I’ve ever seen” with Val Lopez, chair of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band. Lopez described the area on Empire Grade Road within the San Vicente Redwoods as an “oak orchard,” talking about the ways his ancestors would have routinely burned the understory, keeping it clear of competing brush and protecting the large oaks from the possibility of a stand-replacing fire. But in the long absence of fire, Douglas fir and madrone have filled in the forest floor, competing with the oaks for sun and water and producing pound after pound of flammable debris. “So many of the coastal California forests have upwards of 75% canopy cover. They’re very dense,” Stephens says. “The Amah Mutsun believe the ecosystems of the greater Santa Cruz area today have departed from anything in the past that was stewarded by their ancestors.” Today the Amah Mutsun Land Trust and others are working to thin vegetation in the Empire Grade oak orchard through logging and controlled burns, aiming to reduce the canopy cover to just 25%.

“The idea of wilderness as a place devoid of people, that’s pristine? I think you have to go to the moon to find it. Or maybe some place in Antarctica, but definitely, it’s nowhere in California,” Stephens says. “I was intrigued by the concept of wilderness for my whole adult life … until I started talking to Native people. Every member of a Tribe I speak with, when they talk about stewardship, they always use the word active, not passive.”

Land managers in the region had already begun to embrace a more active role before the CZU fires—but these efforts were too little and too late to counter the consequences of over a century of mostly hands-off management. True, Barth says, California State Parks’ controlled burn program at Big Basin was “relatively aggressive” and “way beyond the average level for state parks, and for most other landowners in the region.” Those areas that they’d managed to treat with low-intensity fire seem to have fared better during the big blaze than areas that hadn’t burned, Barth says. But owing to cost, regulations, liability, and a narrow and unpredictable window of acceptable weather conditions for setting management fires, the agency only ever managed to burn what Barth calls a “tiny fraction” of the park’s overall area.

One outcome from the CZU fire, Barth says, is a much wider acceptance of the need for active forest stewardship, including performing controlled and cultural burns and clearing brush and small trees with tools and chainsaws, on a level that’s way beyond what the region has seen since before the early days of the local conservation movement. “Before CZU, the predominant attitude was still, ‘You draw a line around it, and it’s protected—maybe you make a park, maybe you don’t, but it’s good once it’s protected,” Barth says. “That’s obviously, we know now, a mistake.”

“We’re all still learning how to restore native ecosystems, and there’s a lot we don’t know,” Sigona says. “We don’t know if the plants we’re planting will take, if invasive species will be able to be fully eradicated, or how to live in this new place. And of course, climate change just makes it more difficult for us to revitalize our cultural stewardship—and more urgent.”

A stump burn to remove excess fuels on a Sempervirens Fund property, by Ian Bornarth

Looking Ahead

"In Our Hands", by Jane Kim, Ink Dwell

According to a report from the Santa Cruz Mountains Stewardship Network, average temperatures in the region will rise from anywhere between 2.7°F to 5.6°F by 2050. Heat waves will meanwhile become more frequent and severe, breaking existing records by as much as 7.4°F by 2050 and 9.0°F by 2100. Some models show up to an 8.8-inch decrease in annual rainfall by 2050, and others indicate a 6.6-inch increase. But experts generally agree that the rainy season will become shorter and more variable, with a greater portion of the year’s rain falling in fewer, more intense storms, causing more frequent and severe flooding.

Californians can expect twice as many drought years going forward, and those droughts will become more intense. What we now think of as “once in a century” droughts could happen as often as every 20 years by 2100, and “20-year” droughts will happen every 10. And wildfire risk could rise by 16% throughout the Santa Cruz mountains, but this figure masks big differences in local conditions. For instance, experts expect fire risk in the Santa Clara Valley to remain level, while risks to upslope forests are likely to tick up sharply.

In view of climate change, Stephens says the CZU fire—while undeniably tragic—is also an urgent opportunity to restore fire to the landscape relatively safely: “To have so much burn, across so many jurisdictions—holy Toledo, you are never going to have another opportunity to use that reset as an anchor for a future prescribed fire program that should begin now in earnest and never stop, if you want to reduce chances of those types of events recurring in the future.”

More to Explore

- Read Clues About Climate's Future from Redwoods' Past in Part 1 of Redwoods and Climate

- Read What Redwoods Tell Us About Climate, and Water in Part 2 of Redwoods and Climate

- Learn more about How Research Looks Deep into the Past for Clues to Climate’s Future with Jason Addison, USGS, Under the Redwood