Why Cut Redwoods?

Written in partnership with Bay Nature magazine

Why Cut

Redwoods?

photo by Ian Bornarth

A counterintuitive approach to conservation gains urgency

in the face of drought and wildfires in California

BY AUDREA LIM

On any one of her routine treks in Deadman Gulch, Nadia Hamey will move downhill through thick vegetation in the San Vicente Redwoods, a swath of protected redwood forest in the Santa Cruz Mountains about two hours south of San Francisco. She comes here to check the trees: the regiment of giants with their emerald quills, crowned columns that reach hundreds of feet above her head. Their fallen needles lie in a springy bronze mat beneath her work boots. She may stop to consider young redwoods that grow just an arm’s length from another tree, then will use a bottle of paint to spray a light blue line across its blushing bark. The line is a “mark of death” Hamey likes to joke, to make light of the difficulty of her job. An independent forester, she has tended to the region’s redwoods for 21 years, which includes selecting the trees to cut downsee footnote number 1. .“I’m really dictating which trees will go on and get a chance to prove themselves,” she reflects. “It’s seriously exhausting, because it’s so much responsibility. But it’s a really powerful thing to be molding the forest.”

Shaping a redwood forest by cutting down its trees is at once counter to a decades-long ethos of conservation organizations in California and on the leading edge of it, although still not without controversy. While restoration thinning has been supported by research and practiced in California in fits and starts since at least the 1970s, it has been slow to gain momentum. But many conservation groups are now concluding that the millions of acres of logged and damaged redwood forests along the Pacific coast may recover more quickly—in decades rather than hundreds of years—by the cutting of select trees to promote the growth of others. This seemingly counterintuitive approach to preservation has gained urgency in the past decade with the onset of catastrophic wildfires that now routinely burn beyond the control of firefighters throughout the state. The redwoods growing in San Vicente are an early example in the greater Bay Area of conservation groups cutting trees to restore a forest, helping us learn whether these forests can better survive wildfire as the region grows hotter and drier.

San Vicente’s restoration story began roughly a decade ago, a blink of an eye for flora that can live more than 2,000 years. It was around 2011, recalls longtime conservationist Reed Holderman, when local land trusts teamed up to purchase the roughly 13 square miles of forest. It was a massive piece of land in an ecologically vital location near the California coast with potential for public use, but the property required investment—it was laced with dirt roads, held a limestone quarry, and was home to a defunct dam, and the redwoods had been logged over the past century and were now managed for harvest. Nonetheless, pockets of old growth and a rich diversity of species remained. But if the land trusts didn’t purchase the property, it would undoubtedly be divided and sold for development.

Holderman, who was then the executive director of Sempervirens Fund, a land trust created to protect the region’s redwood forests, says the conservation organizations—Peninsula Open Space Trust (POST), Save the Redwoods League, the Land Trust of Santa Cruz County, and Sempervirens Fund—faced a difficult situation: How would they care for a redwood forest that needed so much ongoing attention? “You needed to face the music, right?” he says. “What are we getting into, and what is it going to cost?”

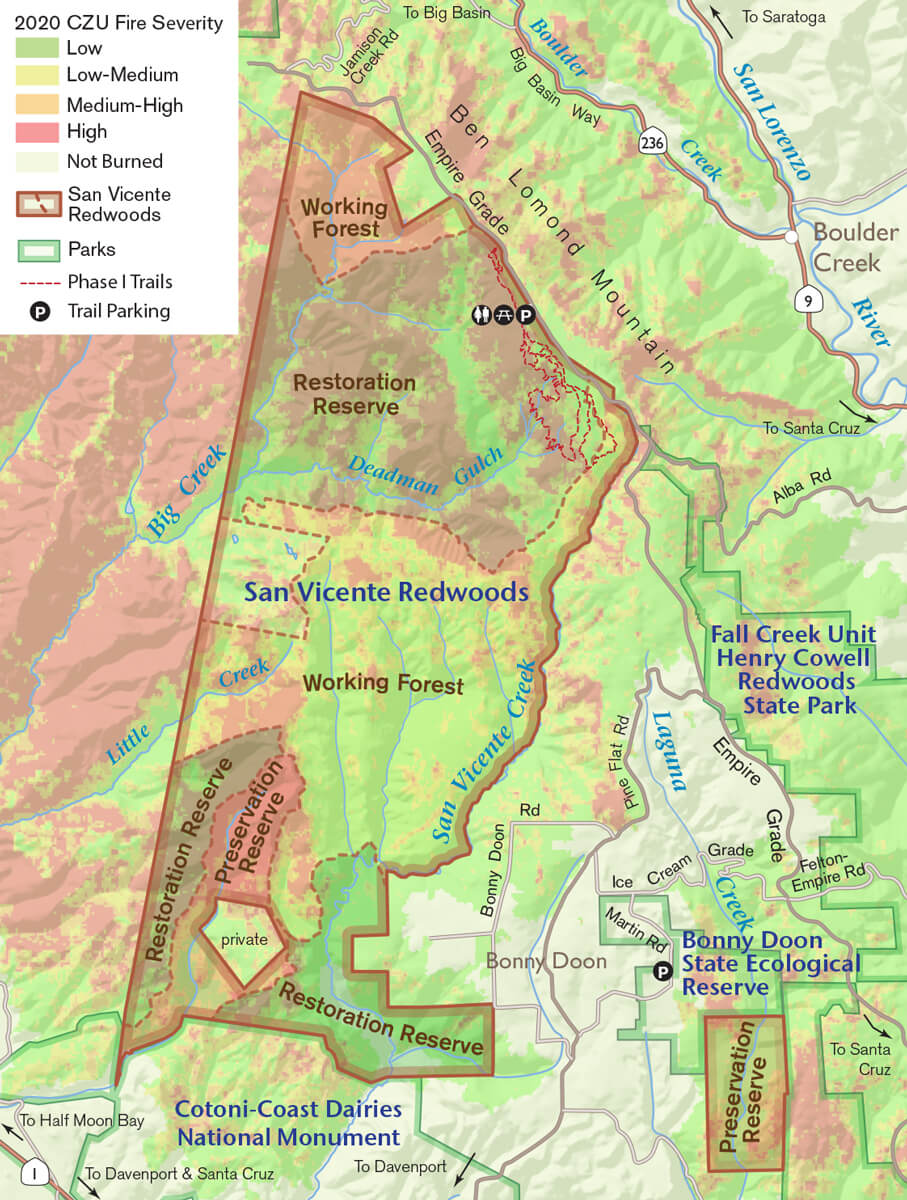

map by Ben Pease at PeasePress.com

California is full of redwood forests that have been changed by people with varied motivations. For thousands

of years, Indigenous tribes harvested plants and lit fires to thin the greenery in the understory of the mostly fire-resilient redwoods, gently coaxing the forests to meet their needs for food, medicine, and shelter. With European settlement and the forced removal of Indigenous people came clear-cut logging, first with handsaws and horses and later with powerful chain saws and destructive earthmovers. The settlers also took the view that all wildfires should be extinguished, largely to protect their lumbersee footnote number 2.

Clear-cutting arrived in the Santa Cruz Mountains in the 19th century, accelerating in the 20th century as the population of Northern California grew, creating demand for lumber as fuel, railroad track, and building material, especially as San Francisco rebuilt itself following the 1906 earthquake. By the 1920s, most of the biggest redwood trees were gone from these mountains, leaving behind armies of stumps. Regardless, a handful of lumber companies eked out a business cutting the region’s smaller trees, as well as managing redwoods with the intent to log them. At the time, people had been so successful at dousing wildfire that the last major one to burn the Santa Cruz Mountains was in 1884see footnote number 3.

Sempervirens Fund purchased one of these heavily altered properties, called Redtree 236, in 2010. The redwoods were crowded shoulder-to-shoulder, on dirt eerily devoid of branches or fallen trunks. The forest “looked kind of artificial,” recalls Holderman. The former owners were “basically growing the trees like crops.” The land trust brought in consulting ecologists, soil experts, and foresters, including Nadia Hamey, to determine whether such a forest could be restored to a thriving ecosystem that supports thousands of other species. “We basically decided to try to figure out, how do you transition an industrial forest into an oldgrowth redwood forest?” Holderman says.

He was unsurprised by the consultants’ prescribed doses of selective logging as part of that solution. And he supported it. Many of his colleagues did not feel similarly. “I got a lot of blowback,” he remembers, bursting into deep guffaws. “Maybe a quarter of my board wanted to fire me.” The controversy was rooted in their belief that environmental stewardship meant letting nature heal itself and that over time, nature would sort it out. In this view, cutting trees was antithetical to conservation.

“Our argument was, ‘well, this is artificial,’” Holderman says. There was no way to know if an industrial forest would evolve into an old-growth forest, a process that can take millennia, but, he told doubters, “We know if we do this [active restoration], it’ll put this on a path to get there quicker.” So in 2011, Sempervirens began for the first time in its 125-year history to experiment with active restoration, cutting some trees to encourage others to thrive, and leaving felled trees on the ground to help restore the soil’s out-of-whack chemistry. Years of removal of fallen snags and old growth by the previous owner had left the soil nutrient poor. Sempervirens began felling trees with chain saws and moving them to modify a redwood forest for the benefit of the forest. “How you manage a forest to restore it, versus how you manage it to produce maximum commercial value, [these] have some overlapping similarities,” says Sara Barth, Sempervirens Fund’s current executive director, “but the end goals are quite different.”

Forester Nadia Hamey marks trees with blue paint she wants cut down. Here, in San Vicente Redwoods’ Deadman Gulch she encourages growth in the biggest oldest trees by felling nearby trees competing for resources.

photo by Orenda Randuch

Nadia Hamey was hired by Sempervirens and POST in 2011 to actively manage San Vicente Redwoods. She walked through the property with the conservation groups to assess the potential and challenges of the landscape. What did the land need and how would they pay for it? “When the cost of doing this came back,” Holderman says,“it scared the shit out of us.” The necessary forest restoration was complex; they knew it would ultimately require tens of millions of dollars, so the groups planned to start small at roughly $250,000 a year. That has grown to well over $1 million annually.

Holderman recalls a time he accompanied Hamey on one of the hikes, the two of them threading their way through the crowded stand of redwoods as she swiveled her attention across the forest-scape and hovered her finger before its specimens. She explained to Holderman that if she were working for Big Creek Lumber Company—a local sustainable logging company that had previously employed her—she would take and sell that tree, that tree, this tree, and that tree under the selective logging rules that applied in the Santa Cruz Mountains. But as a forester for a conservation organization like Sempervirens that was trying to restore an ecosystem, she would choose different trees. She’d also take this tree and that tree, pointing out a couple that were practically huddling in the shadow of their thicker, taller sibling, crowding its personal space.

The idea was to divvy up the 8,532 acres into three groups, each managed with a different goal. About a tenth of the property is preservation reserves, where the old-growth forest is healthy, and she does little besides weed and maintain roads and culverts. Working forest and restoration reserves account for the remaining acres. In the 3,700 acres of working forest—43 percent of the property— Hamey maintains an ecosystem with trees that might be sold. She picks out large, healthy redwoods—though not the biggest, oldest redwoods—that forestry contractors harvest and Sempervirens and co-owner POST sell to Big Creek as lumber. Annual lumber revenue fluctuates, and all of it is directed, along with public grants and private donations, to fund restoration elsewhere on the property and road repair, a cost that also fluctuates, and altogether it has amounted to about $775,000 over the last five years.

“Cutting down trees is hard—really hard. And it feels so counterintuitive to protecting forests,” says Sara Barth. Still, the partner organizations are seeing the long-term benefits of working forests taking shape. “We do not take it lightly. We want a new generation of old-growth redwoods to be established. And when we see the growth and canopies improve in the working forests we are seeing success.”

The goal is to return the restoration reserves to old-growth forest conditions, directing the chain saws away from the trees they would have been aimed at in the working forest. “You flip that on its head in the restoration reserves, and instead of removing some of the larger trees, you pretty much pick the winner,” explains Hamey. Having identified the one big champion redwood—a “future oldgrowth recruitment tree,” in technical language—you then “cut selectively around it.” Some of the accessible logs are removed to reduce fuel for wildfires, while others are either sold or burned for biomass, returning nutrients to the soil. Or as was the case for roughly 30 acres, a prescribed fire burned away the undergrowth and fallen vegetation. Tree-cutting is “the way that we make big adjustments,” Hamey says, and “as long as we don’t introduce weeds, the aftermath is amazingly cool.”

These practices are an attempt to emulate how plants, trees, and animal life interact within a forest ecosystem, enabling it to heal itself from natural disturbances such as wind, lightning storms, landslides, or pest infestations. Research that spans nearly 50 years in Redwood National Park demonstrates that the approach is working. An unnaturally dense second-growth redwood forest site there, called Holter Ridge—which averaged 2,400 trees per hectare in 1978, versus 25 to 90 trees per hectare in old-growth forests—has been thinned periodically since ’78, and the diversity of plants growing in the understory, as well as tree growth, has increased see footnote number 4.

But extensive disturbance can be a problem. Typically, the stumpy clear-cut redwood forests that have been left to recover on their own wind up far denser than old-growth forests. Where the old redwood crowns could sometimes span 100 feet, shading out everything below, felling these giants had the effect of bathing wide swaths of the forest floor in sunlight, encouraging the growth of other sun-loving and often less fire-resistant species. Today, these forests are largely occupied by them, especially hardwoods like tanoak and Doug fir. Yet all the trees, across every species, compete with one another for sunlight, water, and nutrients. The redwoods struggle to regain vigor. So Hamey thins the trees around the biggest redwoods to reduce that competition, a practice known as “crown release.” Her goal is to direct the growth of these mixed-species woods back into flourishing redwood forests that can weather (and thrive on) the occasional, moderate wildfire—their original state before European settlers arrived.

Nadia Hamey was born in the late 1970s and lived in logging camps on Vancouver Island, off the western coast of Canada. She saw industrial clear-cutting level the old forests of the Clayoquot Sound and, as a youth in the ’80s and ’90s, participated in activist blockades and protests. “It’s in my blood to fight,” she says with a chuckle. But her father, a forester, and her mother, a habitat protection officer, advised her that she wasn’t going to achieve her goals by creating roadblocks with her body and stopping loggers from getting to work. “You need to use your brain,” they told her, and “change the law.” So she enrolled at UC Berkeley and earned a degree in forestry.

“I was anti-,” Hamey reflects, on her attitude toward the timber industry. “I wanted to influence the unsound practices of logging.” Yet to learn the practice of forestry after graduation, she worked short stints for two of the biggest clear-cut logging companies on the West Coast, Weyerhaeuser and Simpson Timber Company. Then she landed a job in 2003 at Big Creek Lumber, a family-owned operation in the Santa Cruz Mountains that has been, at times, certified by the Forest Stewardship Council.

Big Creek Lumber is now responsible for selectively logging part of the working forest in San Vicente Redwoods, along with operating its own sawmill and managing other private timberlands. Janet McCrary Webb’s grandfather, great uncle, father, and uncle started the company in 1946, after World War II. They set up a portable sawmill and began harvesting some of the timber on a neighbor’s property in the Santa Cruz Mountains, just a few miles outside of where San Vicente Redwoods now sits. They learned that once cut, redwoods will then sprout into eight or ten new trees, meaning that tree-cutting promoted the growth of the forest. “They were able to pick and choose what trees to thin and realized that thinning worked really well in that redwood forest,” McCrary Webb, now president of Big Creek, explains.

“I really came around to embracing

active management as a way to steward

forests,” says Hamey.

When outside timber operators arrived to clear-cut the forest, the family lobbied alongside advocates for Forest Practice Rules, a set of regulations governed by the California Board of Forestry and Fire Protection, in the Santa Cruz Mountains in the ’70s. The rules outlawed clear-cutting in the region, codifying it in the state’s Forest Practice Rules. Ever since, the only tree-cutting allowed has been “single tree selection.” This means foresters can’t create a gap in the forest larger than half an acre or remove a tree that’s not within 75 feet of another healthy and industrious leafy conifer, like a redwood. The goal, essentially, is to maintain a standing, thriving forest, whether it is managed as a working forest—one steadily supplying wood and other natural resources—or a mostly untouched forest preserve. The rules enabled small companies like Big Creek to remain in business.

Hamey calls her more than 10 years of past work for Big Creek Lumber, and her brief stints at other forestry companies, valuable learning experiences. Applying different silvicultural—forest science and management—practices could achieve wildly varying effects on a forest, nudging the direction of its growth and evolution. She also realized that in areas where the ecosystem was intact and healthy, it made sense to preserve land as wilderness, but when it came to more damaged woodland ecosystems, certain tree-cutting techniques could also return the forest to health. “I really came around to embracing active management as a way to steward forests,” she says.

➊

➋

➌

➍

➎

➊ To help restore heavily burned areas in San Vicente Redwoods (SVR), dead trees are logged and turned into biochar, a soil supplement. ➋ The thick, post-fire understory of SVR’s Deadman Gulch slows restoration efforts in 2024. Note the worker’s orange helmet in the background. ➌ Sempervirens Fund executive director, Sara Barth, visits Big Basin State Park after the CZU fire in 2020. ➍ Smaller trees with pink ribbons will be cut down in SVR’s restoration reserve to spur growth in a larger, older tree. ➎ SVR in 2016.

In August 2020, a thunderstorm rolled through Northern California, shooting more than 11,000 lightning bolts to the ground and igniting hundreds of fires, including four in Santa Cruz and San Mateo counties that merged to burn some 86,500 acres. The CZU Lightning Complex Fire tore into the San Vicente Redwoods from the north, sparing only a few acres and failing to discriminate between areas managed as working forest, reservation reserves, and preservation reserves.

“Before the 2020 fire, I would’ve talked a lot more about how selective harvesting was like a surrogate for prescribed fire, which is a much-needed and missing component of our management,” Hamey says. Both techniques are necessary and complementary. Regular controlled burns can reduce invasive species, promote native plant growth, and remove the brush and small trees that can fuel any natural wildfire.

When trekking through the landscape of blackened stumps, corpses of trees left standing, and redwoods dying from a rot now growing inside following the fire, Hamey could see that the forest required even more thinning. Across the working forest and reservation reserves, it would be necessary to remove sick and damaged trees, regenerate the redwood stands, and deprive future fires of explosive amounts of fuel.

On a workday in August of 2023, the forest vibrated with the feral shriek of chain saws grinding through trunks, climaxing with a crack of branches as a tree crashed down in a dramatic plume of dust. The people Hamey supervised were clearing dead firs and hardwoods from strips of land along the ridgelines and the perimeters of areas that Hamey is restoring. They are creating “fuel breaks” to starve future fires, and “that will hopefully be our holding lines for future prescribed burns,” she explains. Steel behemoths roll through, grinding dead trees into sawdust, grasping fallen logs with their claws, and dragging them across the forest floor. In total the work has created 15 miles of shaded fuel breaks. These are 400-foot-wide strips of land where the hottest-and fastest-burning trees and plants are removed from theunderstory, depriving a potential wildfire of fuel and giving fire crews space to work.

Today, in much of the northern half of the property, where the fire burned hottest, the forest remains dead and charred. The vegetation type has changed, and the hardwood stands previously dominated by tanoak, madrone, California laurel, and Douglas fir have largely converted to shrublands with some hardwoods resprouting. These areas are particularly vulnerable to re-burning. In the coast redwood–dominated stands of trees, the redwoods mostly survived and have resprouted to varying degrees. The larger, older redwoods with the thickest bark have fared best. And the 30 acres of the restoration reserve forest treated with a prescribed burn in February 2020 appeared to weather the blaze far better than the untreated sections surrounding it, according to Sempervirens.

“Having a restoration and working forest in tandem has taught us a lot about not only supporting the forest’s long-term health but also how to prepare for and respond to wildfire,” says Barth. “We approach this work with urgency, humility, and a willingness to adapt based on results. The volume of active restoration work has increased since the fire, and that benefits forests and local communities, now and into the future. Rarely do we fully know what nature will do, so we pursue redwood resiliency in terms of health, habitat, and fighting climate change for millennia.

Buds in a redwood trunk sprout after fire, creating the green fuzzy “sweater” look seen in San Vicente Redwoods in 2022.

Sources

footnote number1

Peninsula Open Space Trust. "From the Ashes, a New Forest Rises - Recovery at San Vicente Redwoods." YouTube, 10 Mar. 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N1rzlbmsN38.

footnote number 2

Stephens, Scott L., Fry, Danny L. "Fire History in Coast Redwood Stands in the Northeastern Santa Cruz Mountains, California." Fire Ecology, 1, 1 Feb. 2005, Pages 2–19, https://doi.org/10.4996/fireecology.0101002.

footnote number 3

Stephens, Scott L., Fry, Danny L. "Fire History in Coast Redwood Stands in the Northeastern Santa Cruz Mountains, California." Fire Ecology, 1, 1 Feb. 2005, Pages 2–19, https://doi.org/10.4996/fireecology.0101002.

footnote number 4

Soland, Kevin R., et al. "Second-growth redwood forest responses to restoration treatments." Forest Ecology and Management, Vol 496, 15 Sep. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2021.119370.

More to Explore

- Learn more about how we're Growing Old-Growth today for tomorrow.

- Read our Climate Action Plan to help redwoods survive so we all can thrive.

- Meet the mushrooms helping San Vicente Redwoods recover from fire.